- Details

- By Josh Spanninga

- Arts and Culture

A large portion of the income for many Native artists depends on how well they do at the right artists markets and festivals, especially during the holiday shopping season.

Unfortunately, with rising COVID-19 cases and strict restrictions on social gatherings, Native artists like Chholing Taha have had to rethink their business strategies.

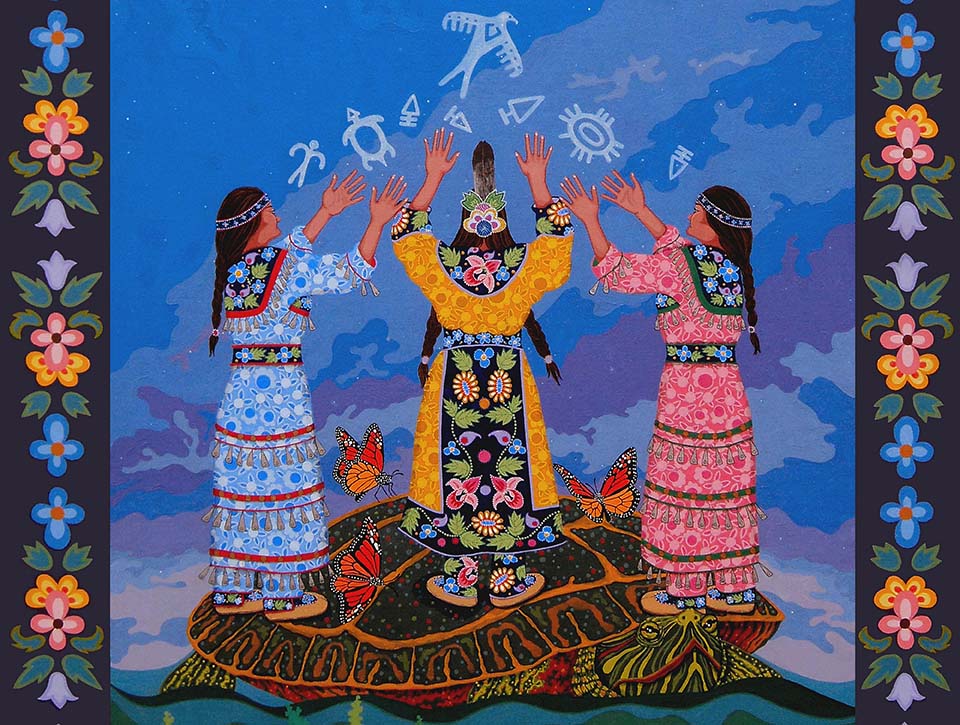

The Cree artist sells a wide variety of items from textile art and paintings to illustrations and hats, but the pandemic caused mounting challenges for her business, all of which left Taha feeling very concerned.

“I had three exhibitions canceled, and then my best selling festivals were all canceled, so I wasn’t really sure what was going to happen, because the holidays can be 60 percent of your income,” Taha told Tribal Business News. “And then several wholesale outlets that I sold to went out of business because of the shutdowns, so they disappeared, which was really worrying.”

Fortunately for Taha, she was able to find a new avenue through which to promote her work: the 2020 Winter Solstice Art Catalog, put together by the Minnesota Indigenous Business Alliance (MNIBA). This catalog marks the first of its kind from the MNIBA, and highlights 15 Native artists from which readers can purchase products directly.

The results for Taha were phenomenal, as evidenced by the activity on her Etsy shop that was among the outlets featured in the catalog.

“I’m comparing traffic from 2019 to now, and I had an 1,119 percent increase in traffic,” Taha said. “It was crazy. It was so high I couldn’t believe it. That has stayed consistent since they started promoting the catalog in November.”

In addition, Taha’s December sales skyrocketed by a 583 percent.

“I didn’t expect it and all of a sudden I’m like ‘Oh my god, I’m busy!’” Taha said.

Pamela Standing, executive director of MNIBA, has heard similar stories from some of the other artists featured in the catalog. Among the artists citing the increased online traffic was Tom Peacock Books, which was featured both in the winter catalog and the MNIBA’s website.

“Their whole business has been with the schools. Since all the schools are closed, their business has really hurt,” Standing said. As a result of being featured but also the winter publication, he’s really seeing a huge uptick in individual orders.”

Sara Agaton Howes, an Anishinaabe artist also featured in the catalog, experienced a similar increase in internet traffic. She attributes that heightened attention to a variety of factors, including being included in various Native artist catalogs, an overall increase in e-commerce in general, and a beefed up internet presence. When the pandemic hit last year, Howes knew that her venture, Heart Berry, would need to change its business structure to focus on internet sales.

“I actually hired somebody right before the pandemic started to just do pop-ups, and she moved up here just to do that. So all summer she was going to be at powwows and conferences, and sales,” Howes said. “I just changed her job, and she does a lot of search engine work and also does our social media marketing.

“(The new role is) something totally different from what she thought she would be doing, but I think we have to do that, right? We have to adapt as soon as things change, and that’s definitely what we’ve done.”

A Focus on the Arts

For more than a decade, MNIBA has been dedicated to supporting Indigenous businesses throughout Minnesota through various projects such as the Native Business Directory and a “Buy Native” campaign. However, MNIBA spent extra time last summer focusing specifically on artist-run businesses.

“We don’t have a Native-led arts organization in Minnesota. We just don’t,” Standing said. “We have lots of different voices, but no one who is serving all of the artists statewide. So we started bringing people together last July, from around 16 organizations, to talk about what this would look like.”

Right before the holiday season hit, one of the artists MNIBA has been working with made a suggestion that struck a chord with Standing.

“She said, ‘You know, it would be really nice if MNIBA did an art catalog,’” Standing said. “And so we just put it together. It’s very homemade.”

For the first round of artists featured in the catalog, MNIBA reached out to local Minnesotans the organization knew through its artist networking efforts. Artists were asked to submit several photos and contact information for the catalog so that customers could reach out directly and eliminate the need for a middleman to sell their products.

Standing then compiled the information and images into a catalog format on her personal computer, published it online, and started promoting it as much as possible.

Moving forward, MNIBA will be releasing Native artist catalogs every quarter, each with a different theme. According to Standing, catalog registration will not be limited only to Minnesota artists, but any artist regardless of tribe/location as long as they are Indigenous.

The March catalog’s theme will focus on running sap, and artists interested will need to pay a nominal $20 fee to be featured.

“That way, we can have professional photographs taken, just so the work really stands out,” Standing said. “We can also hire a graphic designer to lay it all out in catalog form.”

In addition, MNIBA plans to have readers of the catalog cast “Best in Show” votes for their favorite artists, and will award winners functional prizes to help them expand their business skills. Some examples Standing cited for potential prizes included help with grant writing or a free photo kit along Zoom session with a Native photographer to learn how to use the kit.

“I think it’s so great that they support people who are just starting,” said Heart Berry’s Howes. “There are a lot of things that they help small businesses do that I’ve learned along the way, but I’m like, ‘Ah! I wish I could have known that when I first started!’”

The Social Aspect

While the creation of the MNIBA Native arts catalog has certainly boosted sales for artists involved, the scope of the project is much larger than that. MNIBA sees the catalog as another means to forge relationships with Native artists and support them, as well as their tribal communities, in a lasting, substantial way.

“We’re trying to get people to think, ‘If we support our businesses locally and we support our businesses within our traditional boundaries, we can start building stronger tribal economies.’ Then you have a dollar that’s turning over in the tribal community more than one time,” Standing said.

Taha said being featured has certainly helped keep her business afloat financially, but it also has provided her with another benefit: the ability to socialize and develop professional relationships. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Taha used the festival circuit and gallery showings as a way to network with other artists and strike up relationships with potential buyers down the road.

“To have that cut off, suddenly your pipeline of communication into the community and the art world as to what you’re doing, what’s new, explaining the art, all of that interaction — it disappears,” Taha said. “And it’s really quite a big impact.”

With the release of the catalog bringing new customers her way, Taha is now expanding her audience and communicating with people she might not have had the chance to meet on the festival circuit.

“For me, it’s wonderful selling the art, but it’s also about staying in touch and not feeling isolated and being a part of a community and talking things over,” Taha said. “I think both psychologically and spiritually it has a big impact.”