- Details

- By Chez Oxendine

- Economic Development

To help inform better policymaking for Native communities on a national scale, the Center for Indian Country Development at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis realized it needed to take action.

In that process, the Center also respects that it must strike a balance between the need to build new data-gathering tools while also honoring the boundaries that come with tribal sovereignty.

That’s according to Casey Lozar, the director of the Center for Indian Country Development and an enrolled member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes, who said “high-quality data is critical in decision making at all levels of government, with investors that are making investments into tribal economies or businesses, or tribal leaders who are managing those enterprises.”

“Having that foundation is important in making decisions that will become good public policy,” he said.

The importance of data gathering to inform good policy formed a central tenet of a two-day research summit held virtually by the CICD last week. The summit invited panelists to speak on topics ranging from housing, lending, and new data collection techniques the Center has deployed in recent months.

Those techniques are on display in the Native Labor Market tracker, which CICD Vice President Ryan Nunn presented during Thursday’s summit. The tracker gives researchers a new doorway into Native labor force participation and unemployment rates that could lead to new economic policies down the road, Nunn said.

“It struck me and many others as surprising and unfortunate that there were no regularly updated published estimates of labor market outcomes for American Indians and Alaska Natives,” Nunn said. “We think (our dashboard) is a useful contribution in an area that’s been neglected for a long time.”

The Center’s tracker builds off of raw anonymous data published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. While BLS doesn’t include racial demographic data in its final publications, the raw anonymous data includes enough information to make predictions and extrapolations about the labor market as a whole for Native participants, Nunn said.

In the short time since its development, the Center’s analysis of the labor market using the dashboard has already produced interesting findings, said Nunn, who pointed to larger employment gaps for Native populations during economic downturns.

For example, the Center’s tracker found that in 2010 the unemployment rate for Native Americans and Alaskan Natives stood at 15 percent, which compares to a nationwide average of 9.6 percent. Notably, while unemployment numbers were higher during the pandemic, the overall gap was slightly smaller: Native unemployment peaked at 17.2 percent while general unemployment peaked at a national average of 12.9 percent.

“What we see in these graphs really reflects the policy actions that tribal leaders, the Congress, the Fed, and others took during the pandemic. I’d note that the ability to see these data points in something close to real time is key for being able to calibrate all those decisions that policy makers need to make,” Nunn said. “What I take from this is that the initial months of the pandemic were certainly very bad, but the recovery was pretty quick and those gaps have shrunk perhaps more quickly than we (expected them to).”

Data such as what’s presented in the labor market tracker can help show where “pockets of distress” remain even in the face of a roaring recovery, which could then allow tribal leaders to target the most vulnerable populations with new policies and assistance, Nunn said. The data’s effectiveness would only improve with larger sample sizes, which Nunn hopes to achieve in the future.

“I think we could use more data, bigger samples and have more month-to-month precision and richer analysis,” Nunn said. “I think these estimates are important for anyone who cares about how American Indian and Alaska Native workers are faring.”

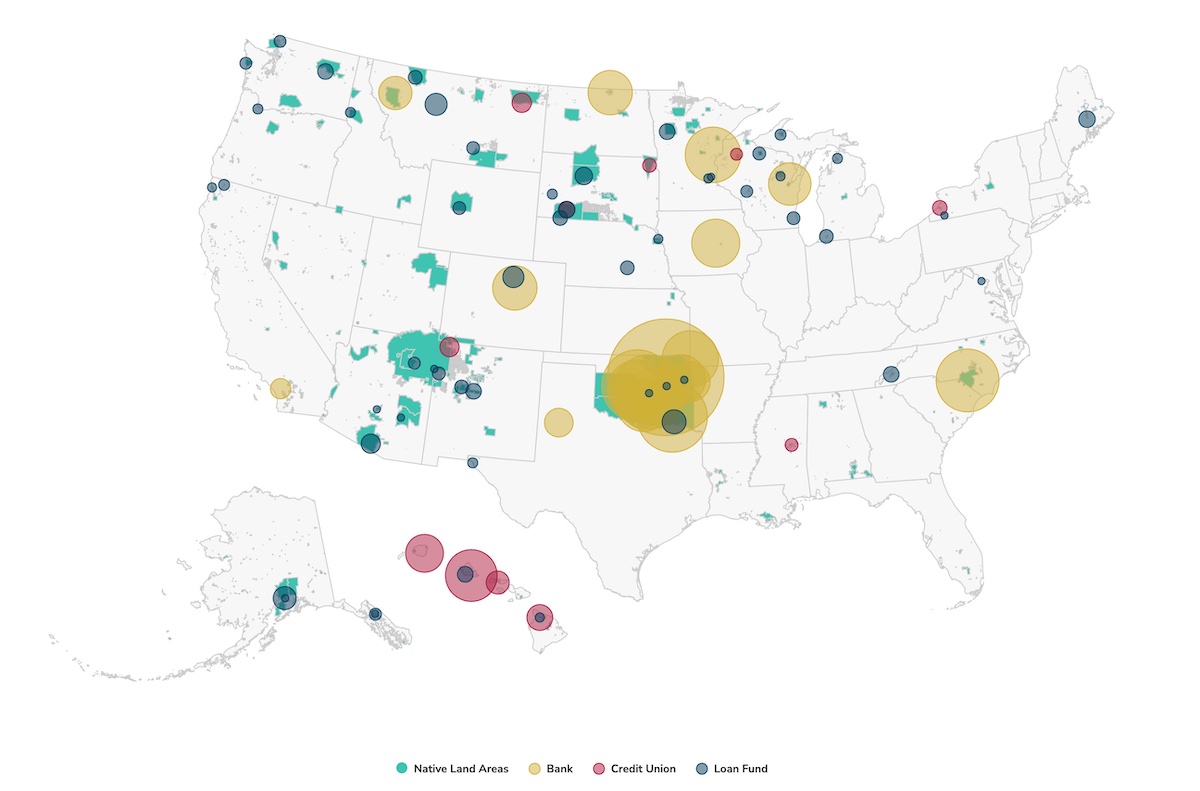

In addition to the tracker, the Center also launched an update to its mapping tool for Native community development financial institutions (CDFIs) and minority depository institutions (MDIs).

The tool, which the Center originally created in 2018, gives a broad view of these organizations’ reach and offers an up-to-date look at the funding circulating within Indian Country, which can be important information for addressing issues such as the lack of access to credit.

“CICD created its mapping tool to help policymakers and those in the banking industry understand the importance and growing impact of Native American Financial Institutions (NAFISs),” Michou Kokodoko, a project director in the Minneapolis Fed’s Community Development and Engagement department, wrote in a report on the data. “The tool can also be used by Native entrepreneurs and home buyers as a guide to NAFIs’ locations and lending portfolios.”

The updated map adds new data points to the previous version that will help CICD better track trends in the future, according to Kokodoko.

Getting more and better data remains a central goal that drives much of the Center’s work, Lozar told Tribal Business News.

“Since we’ve started really using evidence-based policy making, it’s been a longstanding challenge to have access to data. That’s what we’re working on here: to bring professionals in to seek strategies of how to improve data or to work with tribal governments to build new datasets,” Lozar said. “We’re identifying new data sets and identifying ways to increase the quality of that data, and working with tribal governments and entities to build those new sets while respecting tribal sovereignty.”

Lozar stressed the importance of sovereignty, noting that Native Americans, more than many communities, have had their information used against them in discriminatory ways throughout their history.

“For too long, there have been instances of data being weaponized against our people, and so tribal governments have been really thoughtful in how they share data and how to participate in data-sharing agreements that allows them to practice sovereignty,” Lozar said. “This data is coming from our peoples, our families, our businesses and our governments, and so they own it.”

By working with tribal governments to gather accurate, willingly shared data, the Center hopes to help Native communities to better tell their “economic narratives,” and thereby shape policy and attract investors in Indian Country, Lozar said.

“One of the really powerful elements of data sovereignty is that tribes have that choice to share that data, to leverage that data and work in partnership with institutions like CICD and to leverage that research through data to tell that story,” he said. “We’re really focused on using this data to help these communities unlock their full economic potential.”