- Details

- By Chez Oxendine

- Economic Development

A new policy briefing from Harvard argues that a proposed Treasury rule clarifying tax status for tribal businesses could be transformative for Native American economies, potentially unlocking unprecedented growth and development opportunity.

The report, titled “Self-Government, Taxation, and Tribal Development: The Critical Role of American Indian Nation Business Enterprises,” comes from the Harvard Kennedy School’s Project on Indigenous Governance and Development, known throughout Indian Country as “the Harvard Project.” It sheds light on the unique challenges faced by tribal nations and how tax-certainty could be transformative for tribes.

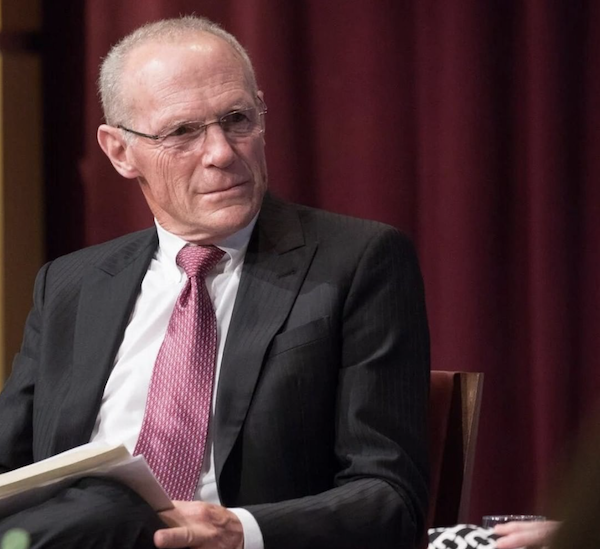

Joseph P. Kalt, the briefing’s author and the longtime leader of the Harvard Project, emphasizes that tribal governments operate in a fundamentally different economic landscape than state or local governments.

The report points out that tribal governments typically lack substantial tax bases and have limited authority to levy taxes of their own. As a result, tribally owned enterprises play an outsized role in funding essential services and programs for their communities.

The contrast is stark: states typically generate less than 3% of their budgets from government-run enterprises like lotteries or liquor stores. By comparison, tribal nations depend on their enterprises — including Indian gaming operations and other non-gaming businesses — for about half of their funding for essential services.

The Harvard briefing coincides with a newly proposed rule that would clarify the tax-exempt status of fully tribally-owned businesses. Currently under a 90-day comment period, with tribal consultation scheduled for Dec. 16-18, the rule would confirm for the Treasury and the IRS that these wholly owned tribal enterprises share their tribe’s tax status. Importantly, it would also make fully-owned tribal enterprises eligible for clean energy tax credits under the 2020 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

“This is really important because ambiguity, litigation, and uncertainty about the tax status of tribal enterprises has been depressing the ability of tribes to raise capital, borrow money and so forth to build those businesses,” Kalt told Tribal Business News. “That's the real concrete impact — the removal of uncertainty, at least with respect to those wholly owned tribal enterprises, will open things up for tribal businesses and bankers. It’s good for everyone.”

The report traces the evolution — and significant progress — of tribal economies since the Indian Self Determination And Education Assistance Act of 1975. Census data cited in the study shows that poverty levels in tribal communities have dropped from 47% in 1989 to 27% in 2018, due largely to tribal business development in gaming, federal contracting, and natural resource management.

However, Kalt’s research suggests that unclear tax rules have hindered further progress for Native nations. The proposed rule could change that, particularly in emerging sectors like renewable energy. Under the IRA law, tribal businesses could benefit from clean energy tax credits, but only if they have clear tax-exempt status, Kalt said.

With tax certainty in place, tribes can begin to grow those economic engines further by removing a major barrier to credit access — a well-documented problem in Indian Country, per prior Tribal Business News reporting. Tax certainty provides revenue clarity, Kalt said, making it less of a risk to bet on tribal businesses in the first place.

“If the bank issues a loan to a tribal enterprise, the bank wants to get paid back, but if the federal government wants a big chunk of that through taxes, maybe they can't be paid back. It's made even worse if there's uncertainty,” Kalt said. “Clearing that up means you're giving everybody better certainty that yes, tribes will be able to pay it back.”

The study highlights a gap in the proposed rule: it doesn’t address partially-owned tribal businesses. Peter Larson, a partner at law firm Lewis Roca in Phoenix, expressed disappointment with the omission. According to Larson, IRS guidance suggests the tax status of these part-owned tribal entities won’t be clarified “anytime soon.”

“It is a real bummer that the proposed rule did not take that into account, because I was hoping that tribally owned businesses or partially owned businesses would fall into the same category,” Larson said. “Seems like that's going to be on the backburner at least for a little bit.”

The arrangement under the proposed rule could affect the structure of deals going forward, particularly around programs like the clean energy tax credits direct pay program under the Inflation Reduction Act, Larson said. Tribes may seek to completely own energy companies set up to develop projects, rather than receiving tax credits and selling them to someone else as might be common under the current rule.

“Historically, whenever there's a tax credit deal out there and you have a tax entity not subject to tax, you're kind of setting up a sale to the taxable partner. There's always some risk and a lot of unknowns, so the tribal entity doesn't get the full value out of the credits,” Larson said. “Now there's a path to getting full value for those tax credits.”