- Details

- By Chez Oxendine

- Energy | Environment

Tensions flared between Alaska Native groups, environmentalists and the federal Bureau of Land Management during a congressional hearing Wednesday about legislation to reverse Biden-era protections against oil drilling and energy production on Alaska’s North Slope.

The legislative hearing centered on H.R. 6285, or Alaska’s Right to Produce Act. The bill, introduced in the House in early November by Representatives Pete Stauber (R-Minn.) and Mary Sattler Peltola (D-Alaska.), seeks to reinstate leases on oil tracts canceled by President Joe Biden’s administration, and overturn protections announced in September of this year.

While two local tribal groups advocated for the legislation, insisting it would pave the way for much-needed economic development in their marginalized communities, others expressed concerns about its potential environmental impact. Karlin Itchoak, a member of the

Nome Eskimo Community and the Alaska Regional Senior Directory for The Wilderness Society, warned the legislation could unleash environmental hazards in the region that would harm both tribal communities and surrounding ecosystems.

“Oil and gas drilling would have devastating impacts on this sensitive ecosystem, caused by the massive infrastructure needed to extract and transport these fossil fuels,” Itchoak told the committee. “Drilling the Arctic is risky, would fragment vital habitat, and chronic spills of oil and other toxic substances onto the fragile tundra would forever scar this landscape and disrupt its wildlife.”

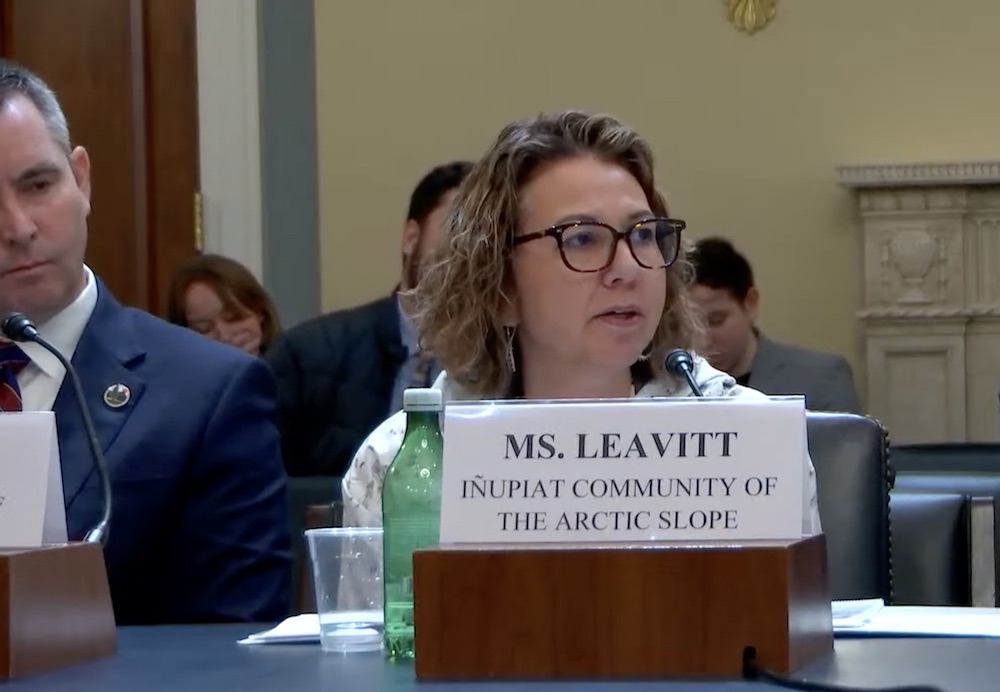

Doreen Leavitt, director of Natural Resources and Tribal Council Secretary for the Inupiat Community of the Arctic Slope (ICAS,) argued that the Biden administration’s actions amounted to a slight against Alaska Native villages’ right to self-determination. By instituting federal environmental protections in September without a government-to-government conversation, Leavitt said, the administration foisted protections the tribe didn’t want.

“The unilateral actions that took place on September 6 — without prior consultation with the only Indigenous group who calls the affected lands home — is not just a dereliction of duty, an issue of mere miscommunication, or disrespect for Indigenous voices. It is a violation of the rule of law,” Leavitt said. “...our self-determination is something to be fought for still to this day. This includes continuously reminding Washington about our legal rights, including calling out the administration for shirking its government-to-government consultative responsibilities to the North Slope Iñupiat.”

Charles Lampe, president of the Kaktovik Inupiat Corporation and a member of the Native Village of Kaktovik community, echoed the sentiment. Despite promises made by Congress through the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) in 1971 and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act in 1980, the tribe and its corporation find themselves back in front of Congress, once again asking their rights be honored, Lampe said.

Lampe thanked Rep. Stauber for introducing the legislation, which would open up “crucial” economic development and resource avenues for the villages along the Northern Slope, he said.

“I am here to continue the legacy of our past leaders to fight for what is rightfully ours – these are our homelands,” Lampe said. “We fought to have the Coastal Plain open for oil and gas leasing many times in the past and we continue that fight today.”

The Alaska Right to Produce Act is a response to a decision made by the Biden Administration on Sept. 6, in which the Department of the Interior announced new protections for the Arctic Refuge and more than 13 million acres of land in the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska, or NPR-A. Those protections included canceling existing leases on the land issued by former President Donald Trump’s administration, prohibiting new leases, and calling for reviews every five years by the Bureau of Land Management as to the need for expanding the protected areas.

For Leavitt and Lampe, much of their tribes’ consternation centers on what Lampe called “continued efforts to turn our homeland into one giant park.” That would stymie economic development and in turn, eventually, subsistence efforts. Federal protections on the Refuge and Petroleum Area already restrict tribal activities in those areas. Biden-era protections would only enable those restrictions further, Lampe said.

“Since all these federal actions we have been subjected to eco-colonialism – we are treated as colonists on our own lands and are subject to federal approvals for almost everything we need,” Lampe said. “Our experience is that living inside the Refuge is one of paternalistic behavior by the federal agencies.”

The Wilderness Society’s Itchoak testified that the Alaska’s Right to Produce Act would reinstate “hastily and unlawfully” leases issued by the Trump administration that would prioritize extraction above environmental safety efforts.

Those leases were issued in 2020, during the Trump administration’s waning days, and their sudden reinstatement - within 30 days after the proposed Act’s passage - would interrupt ongoing environmental surveys that could provide a broader view of potential impacts on the Inupiat and neighboring Gwich’in communities, Itchoak said. It wasn’t just the Wilderness Society supporting the Biden protections, either: Itchoak pointed to Gwich’in tribal governments around the Native Village of Venetie and the Arctic Village Council as supporters of the protections.

“In contrast [to Trump’s decision], the Biden administration’s draft environmental impact statement recognizes conservation needs and Indigenous rights in the region and presents a strong opportunity to go further to protect the Refuge and the plants, animals, and people who have relied on it since time immemorial,” Itchoak said. “We urge this Congress to reject attempts to legislate the opposite outcome, as the bill before you today would do.”

Alaska has a high concentration of energy employment with nearly 19,000 energy workers, which represents 8.3% of the state’s total employment, according to a 2021 report from the Department of Energy. The report noted the median wage for all energy workers in Alaska at $28.87, which is 51% above the national median wage of $19.14.

Responsible resource extraction has, since the passage of ANCSA, become a cornerstone of the regional economy, Leavitt told the committee. Further limiting already restricted land usage threatened to further upend a fragile economic foothold for the Inupiat. The tribe would have shared these comments with the Biden administration had they ever been consulted, Leavitt said.

“By curtailing land available for these projects, the federal government was also foreclosing any economic opportunities that would provide stability for our communities and culture,” Leavitt said. “...further consultation never materialized. On September 6, ICAS and all other North Slope tribes, cities, ANCSA corporations, non-profits, schools, and the collective regional elected leadership were blindsided by this administration’s decision.”

It was a reversal of prior federal policy that led the Inupiat to begin energy production in the first place, Leavitt said. The community’s relationship with “responsible” energy extraction means that suddenly depriving them of that access, or impeding necessary expansion, will choke development in the area.

That’s why the Inupiat should have been consulted and should have further input on rule changes and restrictions in the region, she told the committee.

“We have forced a seat at the table to ensure our communities would not be left behind,” Leavitt said. “Without an economy, our communities are not sustainable; without our communities, our culture begins to die as more and more of our people are forced to leave to find economic opportunity elsewhere.”

That calls into question the rights of other Indigenous communities in the area - namely the Gwich’in, who rely on caribou herds in the area that could be damaged or stifled by the onset of energy extraction and the associated infrastructure, said Itchoak.

The Alaska’s Right to Produce Act “represents a dangerous end-run” around existing environmental policies, as well, Itchoak said. He pointed to the Act’s interactions with the National Environmental Policy Act, the Endangered Species Act, and provisions of the Alaska National Interest Conservation Lands Act, essentially bowling over extant policy.

“It then purports to close the courthouse doors, stripping all courts of jurisdiction to hear legal challenges to agency decisions that may violate the law, raising grave questions about constitutional separation of powers,” Itchoak said. “And it effectively strips the Secretary of the Interior’s long standing authority to suspend or cancel unlawfully issued oil and gas leases.

Far from enabling Native sovereignty in the area, the Alaska’s Right to Produce Act would inhibit future efforts toward co-stewardship and management, which has proven a popular method of consultation and cooperative government for environmental causes between tribal and federal agencies in recent years.

“It fails to recognize and account for past Indigenous land ownership, past and current Indigenous land stewardship, and historical and present injustices toward Indigenous peoples,” Itchoak said. “It would legislate one view of the future for Alaska’s Arctic, locking in decades of industrial development and climate-disruptive emissions that we simply cannot afford.”