- Details

- By Chez Oxendine

- Energy | Environment

Northern California’s Yurok Tribe drew more than 250 people to its first Tribal Offshore Wind Summit last week with an overarching goal - to help tribes to get a better understanding of a burgeoning sector in clean energy development that could impact traditional sources of food, culture, and income for Native communities.

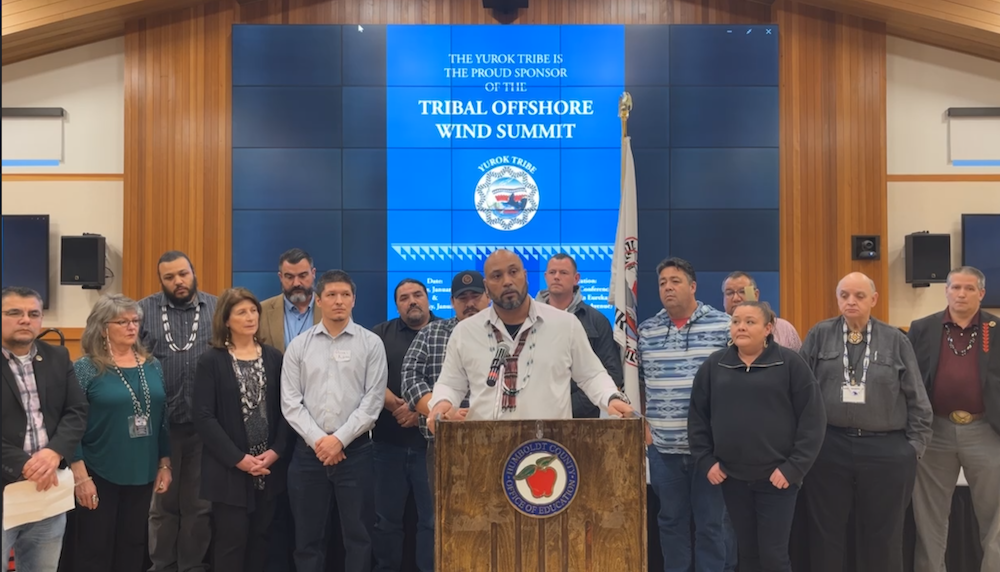

The summit at the Sequoia Conference Center in Eureka, Calif. brought together tribal leaders to critically examine current and future offshore wind projects. Representatives from federal agencies, the offshore wind industry, and northern California’s Humboldt Bay Harbor District provided updates on two federally approved projects off the Yurok coast in Humboldt County as examples of currently in development projects in the emerging industry.

Amid the conversations held at the summit, a central point emerged: there can be no responsible offshore wind development in tribal areas without tribal consent and input, tribal leaders asserted.

So far, tribal input has not been considered or sought sufficiently by federal and state authorities, which has caused worry among leaders at the summit, who vowed to work together to demand a seat at the table as industry develops.

"We've come together with our brothers and sisters from the North and the South to move forward in a good way on renewable energy," said Robert Hemstead, vice chairman for the Trinidad Rancheria, during a press conference after the summit.

One hot topic of conversation during the summit was the two currently planned Humboldt area wind farms, which will create an estimated 1.6 GW of energy, enough to support up to 1.6 million homes, according to experts.

Yurok Tribe vice chairman Frankie Myers has questions about what kind of impact the offshore wind farms, which have leased land area of 583 square miles, will have on the environment. Just because these technologies are painted as being green, doesn’t automatically mean they’re 100% good for the local community, he said.

The Yurok have been burned by what was supposed to be renewable energy before when hydroelectric dams along the Klamath River decimated the local salmon population, significantly impacting commercial and subsistence fishing in tribal territory, Myers told Tribal Business News.

“Simply stamping something renewable means very little to us,” Myers said.

The Yurok put on the summit to “empower tribes to play a greater role in determining if, when and where offshore wind projects are established,” Yurok Chairman Joseph L. James said. “We don’t want to see another extractive industry take advantage of our natural resources and contribute little or nothing to the local community.”

Questions remain regarding the impact of the wind farms on local marine life. While other offshore wind farms have had minimal impact, none of them have been built in such deep waters, nor at such a scale, James said. That is causing concerns about tangling whales in cables, or driving fish away.

Tribal leaders also expressed concerns about their role in the decision making process. The Yurok contend that the ocean is unceded territory, and they remain stewards of their coastal waters. So far, tribal leaders claim, federal and state processes for obtaining consent for wind farm activity have failed to include Yurok input, the tribe wrote in a post-summit statement.

Moreover, wind farm activity is going to drive massive industrialization of the port and surrounding areas, creating a hive of industry in an area where buzzing excitement around a new resource has not historically gone well for the Yurok, Myers said. He pointed to gold rushes, a hurried timber industry, and the aforementioned hydroelectricity as examples.

“I think a lot of others are coming to the same conclusion,” Myers said. “We don't know whether off-shore wind is something we could support or oppose, because we don't know what it's going to look like.”

“We're building this industry as we go,” Myers said. “We look back at the industries that have been built within our area, and we want to make sure those devastating impacts don't happen again.”

Myers again points to the dams, which are an especially sore point for the Yurok, Myers said. Even as the hydroelectric dams denied tribal members access to a traditional source of food and income, much of the reservation remained without power until 2016.

Now those dams are being removed thanks to tribal protests, creating what Myers called “the largest salmon restoration effort in world history.”

“As of this week, we just blew the plug on the last dam, so the river is flowing freely under all four days. It's an amazing time in the Klamath Basin - all four of the facilities will be removed in the next move. Our tribal members, right now, as we speak, are out planting seeds, acorn trees, revegetating the historic riverbanks. There's a lot of hope in the basin right now,” Myers said. “What we've seen is our river running free. The sounds of the river are in the canyon that hasn't been there in some places for over 100 years.”

Tribes at the summit, Myers said, plan to keep a closer eye on energy projects in their areas as a result. They don’t want another dam situation, where a supposedly renewable resource destroys cultural resources.

“The day we're watching the plug on the last dam be blown on the other end of the basin, they're announcing half a billion dollars to be spent on the harbor for offshore wind. Same day,” Myers said. “We will not let the offshore wind companies follow in the same footprints as their predecessors. These projects need to be done right or not at all.”