- Details

- By Chez Oxendine

- Indigenous Entrepreneurs

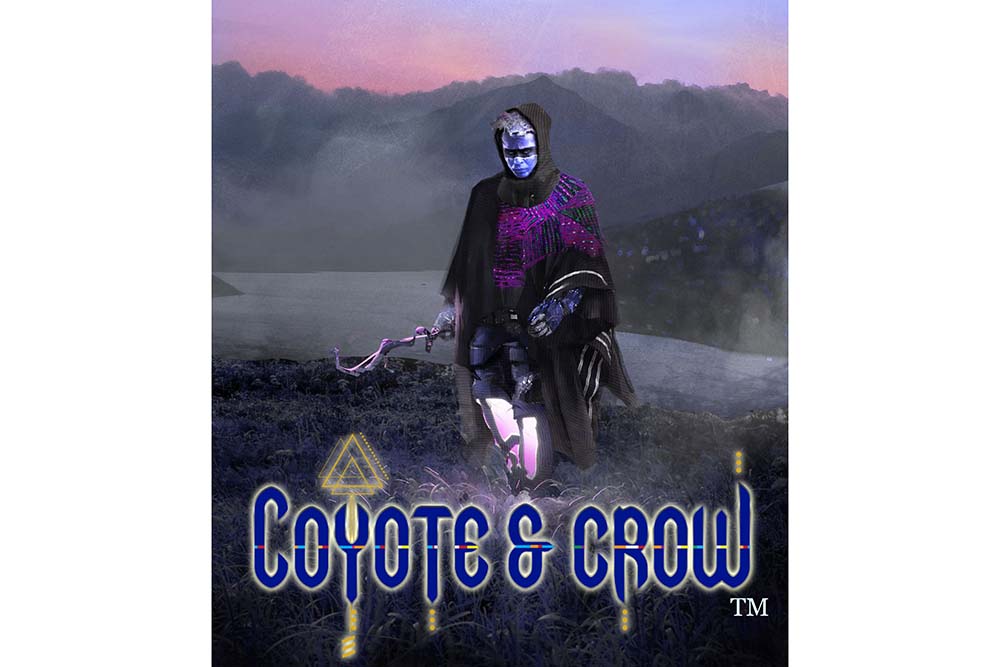

Game designer and Cherokee tribal member Connor Alexander put together the tabletop roleplaying game Coyote and Crow with an initial ask of $18,000 on Kickstarter.

The goal was to get the book printed and into people’s hands, and then to use profits from book sales to continue writing expansions and material for the new RPG.

As the Kickstarter period wore on, however, support for the game surged well past his initial expectations. On its first day, Coyote and Crow’s backers soared into the thousands, contributing more than $100,000 toward the print run for the game, which is set in a sci-fi world where European colonization never occurred.

“We knew we were tapping into something unusual before we launched. What really threw us was just how many people this would speak to,” Alexander said. “The volume of backers and the enthusiasm has just been overwhelming.”

As of this writing, with three days left to go for the Kickstarter campaign, Coyote and Crow has garnered more than $790,000 in support from 11,603 backers. Many of the people reached out through personal messages to relay how much the game means to them as Indigenous people, Alexander said.

“I think we’ve all gotten so used to representational table scraps from mass media that when something different comes along, it feels really fresh and vital, even though what I’m trying to do here should frankly just be the standard,” Alexander said. “A game about Indigenous people created by Indigenous people should not be groundbreaking.”

Coyote and Crow represents a venture into an exploding industry. Tabletop gaming has grown into a $14 billion industry in the United States, according to a 2020 report from analytics company Statista. More than 40 million people across the world play the industry’s most popular title, Wizards of the Coast’s Dungeons and Dragons.

It’s also a space almost completely bereft of Indigenous-led, Indigenous-focused content, according to Alexander. That’s typically the case for all media, but in this instance Alexander said he feels his team can do something about it.

“There are so many great stories out there. I just want to help the people that want to share those stories find a way to get them to a new audience using my own skill set,” Alexander said. “My hope is that Coyote and Crow is just the latest log on the fire in our current media rebirth. It feels like our game is part of a larger moment.”

Coyote and Crow’s swell of popularity has carried it into marketing pushes such as a live streamed playtest with The Orr Group’s Roll20.com platform, which allows traditional pen and paper RPGs to be played using a virtual tabletop. Alexander attributed the product’s success to the work of his team and the “clarity” of the game’s vision.

Beyond those aspects, Alexander also cited a “general hunger” for something outside of the standard science fiction and fantasy tropes that have grown so dominant in the role playing games industry.

“I’m not knocking them, but I think fans of science fiction and fantasy have been really lucky the last twenty years and have had some amazing worlds to play in. But I think the classic tropes of those genres often rely on their similarities to each other — usually their European roots — to feel comforting to new audiences. I think that has some diminishing returns,” Alexander said. “If you look at movies like Black Panther or video games like Horizon Zero Dawn, people everywhere were drawn to them because they felt fresh. I think Coyote and Crow taps into some of that.”

PLANS SHIFT

In the wake of the overwhelming support, Alexander has changed up his plans for Coyote and Crow. After intended to launch primarily a print and digital run of the book with some online support, the creator now aims to create a mobile application and an online, editable encyclopaedia for the game’s fictional “Kag Chahi” language.

Alexander and his team of Native American writers and artists also have expansions and accessories planned for the game’s future, steps critical to keeping a game alive, he added.

“It’s important that we use the energy and money we’ve been afforded as fuel to build community. I think that’s true with any product, but it’s even more important with role playing games. You need to help players find each other. You have to bring new people to the hobby and you absolutely have to be supportive on their journey,” Alexander said. “If you just drop a book on their doorstep and disappear, the game will be forgotten in a year. So much of what we are talking about internally is engaging people once they have the book.”

The Kickstarter’s runaway success also could spell changes ahead for Alexander, who currently works for a board game distributor and publisher.

“I’m likely leaving my amazing day job to take a risk and do Coyote and Crow full time,” Alexander said. “It’s a big leap for me but I feel like to honor everyone’s enthusiasm, this needs my full attention.”

In addition to stated stretch goals like the mobile app and online language documentation, Alexander said he hopes to get the book translated into other Native languages.

“I think game play could be a powerful tool in helping keep languages alive,” he said.

More translations could improve accessibility, which has been a core part of Alexander’s push from the start. In addition to making all the tools necessary for gameplay digitally available, Coyote and Crow’s Kickstarter has given backers the option to donate copies of the book to reservation libraries, so that the game is available for anyone in those areas to play.

That initiative has been a massive success, Alexander said.

“We’ve had almost 3,500 books pledged for donation so far and we’ll likely hit 4,000 before we’re done. That’s just mind boggling. Many role playing games don’t have entire print runs that size, let alone donated copies,” Alexander said. “There’s an enormous amount of generosity at play here. I think many folks who can afford to buy a $50 game book have enough money on hand that they feel like they want to give back somehow.”

Even with these massive successes and displays of generosity pushing print numbers up and up, Alexander says the timeline for the game’s release hasn’t “changed too drastically.” His team consists of one group working on the book itself, and a second group working on the game’s digital presence and stretch goal integration.

The plan is to have the digital release in November this year, and for physical books to arrive in December. Alexander isn’t afraid to push those back if it means a higher quality product, however.

“Chances like these don’t come along often and I want to make sure our whole crew looks back on this project as something they were proud to be involved in,” Alexander said. “Hopefully, this is just the beginning for Coyote and Crow.”