- Details

- By Megan O’Matz and Joel Jacobs, ProPublica

- Finance

The sprawling business empire created by tribal leaders in northern Wisconsin was born of desperate times, as the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians faced financial ruin. Its subsequent success would be built on the desperate needs of others far from the reservation.

This story was originally co-published by ProPublica, a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom, and Wisconsin Watch. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

The tribe had made some poor choices as it sought to expand its fortunes beyond a modest casino in its home state of Wisconsin two decades ago. Grand plans for a floating casino off Cancun, Mexico, collapsed, and a riverboat gambling venture in Mississippi required more cash than the tribe had on hand.

The resulting loans — $50 million in bonds issued in 2008 at 12% — proved crushing. Struggling to make debt payments, tribal officials soon were forced to slash spending for essential programs on the reservation and lay off dozens of employees.

Protests erupted, with demonstrators barricading themselves inside a government building and demanding audits and investigations. When angry tribal members elected a new governing council, it refused to pay anymore. The tribe defaulted on a loan it had come to regret.

The LDF tribe turned to the one asset that could distinguish it in the marketplace: sovereign immunity.

This special status allowed it as a Native American tribe to enter the world of internet lending without interest rate caps, an option not open to other lenders in most states. The annual rates it charged for small-sum, installment loans frequently exceeded 600%.

Business partners, seeing the favorable math, were easy to find. So, too, were consumers who had run out of options to pay their bills. Their decisions to sign up for LDF loans often made things worse.

ProPublica traced the key decisions that put LDF on the path to becoming a prominent player in a sector of the payday lending industry that has long skirted regulation and drawn controversy.

LDF did not just dabble in this type of lending; it fully embraced it. Like other tribes that have taken this route, LDF built its success on a series of complex business arrangements, with roles and motives difficult to unravel.

Over time, ProPublica found, LDF signed off on deals involving outsiders with histories of predatory practices — associations that carried profound implications for the tribe. Not only did they put the tribe’s reputation at risk, they generated a barrage of costly lawsuits and questions of whether LDF was allowing partners to take advantage of tribal rights to skirt state usury laws.

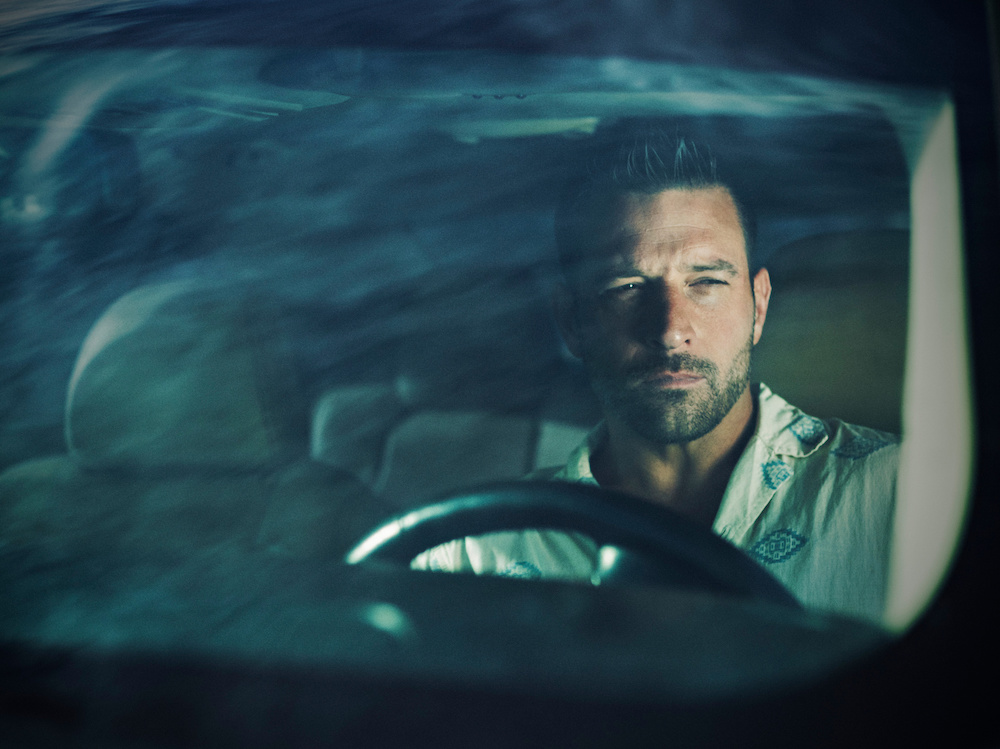

In Boston, Brian Coughlin initially had no idea that a Native American tribe was involved in the small loan he took out with a high interest rate. He only learned about LDF after he filed for bankruptcy to seek protection from his creditors.

“I was definitely surprised,” he said. “I didn’t think they operated things like that.”

During the bankruptcy process, an LDF partner still hounded him to pay, which Coughlin said pushed him to a breaking point and a suicide attempt. Federal law prohibits chasing debtors who have filed for bankruptcy, and Coughlin sued the tribe in a dispute that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Last year, the court — in a decision with far-reaching implications for tribes — ruled that LDF could be held liable under the Bankruptcy Code.

Brian Coughlin initially had no idea that LDF was involved in the small loan he took out with a high interest rate. He filed for bankruptcy, but an LDF partner still hounded him to pay. (Credit:Bob Croslin for ProPublica)

Brian Coughlin initially had no idea that LDF was involved in the small loan he took out with a high interest rate. He filed for bankruptcy, but an LDF partner still hounded him to pay. (Credit:Bob Croslin for ProPublica)

His and other consumer lawsuits paint LDF as a front for outsiders who take an oversized cut of the proceeds, leaving LDF with only dollars per loan. Interviews and ProPublica’s review of records also show how heavily LDF relies on its partners for most of the essential operations. These descriptions are disputed by LDF, which has told ProPublica that it merely is outsourcing for much-needed expertise while still maintaining control.

In a statement to ProPublica this year, John Johnson Sr., LDF’s president, described the tribe’s lending business as “a narrative of empowerment, ethical business practice, and commitment to community enrichment.” He has declined to be interviewed and did not respond to written questions for this story.

Over time, LDF has set up at least two dozen internet lending companies and websites, ProPublica determined. Its loans are so pervasive the LDF tribe showed up as a creditor in roughly 1 out of every 100 bankruptcy cases sampled nationwide, as ProPublica reported in August.

This year, LDF and some of its business affiliates agreed to a federal class-action settlement in Virginia that, if finalized, will erase $1.4 billion in consumer debt and provide $37 million in restitution. Tribal defendants are responsible for $2 million of that; the tribe in a statement has indicated that its business arm would pay.

Tribal officials have consistently denied wrongdoing. A newsletter to tribal members as LDF was starting up its venture said the tribe “is not practicing any type of predatory lending.” In his statements to ProPublica for the August story, Johnson stressed that the tribe complies with tribal and federal law, that its lending practices are transparent, that its collections are done ethically and that the loans help distressed borrowers who have little access to credit.

LDF leaders have not publicly stated any desire to alter their business practices, even as some community members express concern.

“Feeding greed with unscrupulous business practices is crushing us,” one LDF member recently wrote on a community Facebook page.

“The Money Is Dirty”

After the bond debacle in the 2000s, LDF leaders felt stung by their outside financial advisers, believing they were deceived about the terms of the transaction and risks involved.

Moving forward, they wanted someone they could trust. They found that in Brent McFarland.

McFarland was not a tribal member, but he grew up near the reservation and had friends on the Tribal Council. McFarland, an investment adviser who’d run a restaurant and worked in real estate, offered some helpful advice to the tribe, and the council eventually hired him for a wider role. He helped it establish the Lac du Flambeau Business Development Corporation in 2012, governed by a board answerable to the Tribal Council. And he looked for ways LDF could make money, apart from gaming.

“I ended up meeting some people that were doing online lending,” he said in an interview.

Tribes could get into the industry — attracting willing partners with expertise in lending — without putting up any capital because sovereign immunity was its own bounty.

But as certain as LDF was that state laws wouldn’t apply to its operations, the tribe took a careful approach. LDF decided it would not lend to people in Wisconsin, including its own members. “It keeps our relationship with the state of Wisconsin healthy,” McFarland told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

Peter Bildsten, who ran the state Department of Financial Institutions then, remembers visiting the reservation as it was embarking on the new venture. He recalled that he met some of LDF’s business partners, who recognized that the lending operation would be extremely lucrative but also potentially controversial.

“They talked about yeah, we are doing it, and we know there’s virtually nothing you can do about it and especially if we don’t lend to any people in Wisconsin. You can’t do anything,” Bildsten said. “It was almost kind of a dare.”

Many tribes, still suffering from a legacy of racism and inadequate federal resources, struggle to find economic solutions for their people. McFarland, who no longer works for LDF but does consulting for tribes, defended LDF’s decision to move into high-interest loans as a legitimate option.

“The business is offering a service where the interest rates and cost of borrowing are well disclosed to consumers,” he told ProPublica in an email. “It’s expensive, but if used responsibly can be more affordable than many other options. The costs and risks are not hidden from consumers.”

Johnson, LDF’s president, has said there was a rational reason for the tribe’s business partnerships: It needed outside expertise as it entered a new industry.

“But let me be more specific: Zero I.T. enterprise architects, data analysts, or marketing strategists lived on the Lac Du Flambeau reservation when the Tribal Council decided to enter this industry,” he wrote in an email to ProPublica in August.

LDF’s partners run their operations far from tribal land. ProPublica identified several Florida lawsuits that allege a straight-forward process: “The LDF Tribe mints a new ‘tribal’ limited liability company, supposedly organized under Tribal law, for each new investor. Each new investor then runs his or her own ‘tribally owned’ website, offering consumers loans at interest rates between 450% and 1100% annually.”

Those cases were settled or dismissed without LDF addressing the allegations.

LDF does not publicly disclose its partners. ProPublica identified one of them as RIVO Holdings, a fintech firm based in a high-rise in downtown San Diego that has serviced two LDF websites.

First image: The Lac du Flambeau Business Development Corporation in Wisconsin. Second image: The office building where RIVO Holdings operates in San Diego. (Credit: First image: Tim Gruber for ProPublica. Second image: Philip Salata for ProPublica.)

First image: The Lac du Flambeau Business Development Corporation in Wisconsin. Second image: The office building where RIVO Holdings operates in San Diego. (Credit: First image: Tim Gruber for ProPublica. Second image: Philip Salata for ProPublica.)

RIVO is an acronym for respect, integrity, value and opportunity. The company’s founder and CEO is Daniel Koetting. His personal website touts his employment of “over 200 local employees at RIVO.” His brother Mark, of Kansas, managed a separate lending portfolio for the tribe.

The brothers entered the tribal lending industry after facing regulatory scrutiny for previous lending operations. In 2006, Califonia issued a cease-and-desist order to both men for unlicensed lending; Daniel Koetting received a similar demand from New Hampshire in 2011.

Initially, the Koettings partnered with the Big Lagoon Rancheria tribe in California to offer high-interest loans beginning in 2013. But that relationship began to fall apart several years later.

The tribe alleged that the Koettings surreptitiously pushed customers to new lending companies set up with LDF, and an arbitrator awarded Big Lagoon Rancheria $14 million in 2018. Years of litigation followed as the Koettings fought the decision. The case is still pending.

“I actually called Lac du Flambeau and warned them and informed them that they were getting into business with Big Lagoon’s client list,” Virgil Moorehead, Big Lagoon Rancheria’s chairperson, told ProPublica.

Joseph Schulte Jr., who once worked at RIVO, likened one area of the company’s San Diego office to a Wall Street trading floor, with exuberant staff celebrating short-term wins, such as meeting daily sales goals. To keep the staff pumped up, he said, management brought in pallets of free Celsius energy drinks.

“People were making a lot of money working there,” Schulte said of RIVO Holdings.

Although figures for LDF’s loan portfolios are private, Daniel Koetting’s previous venture with the Big Lagoon Rancheria amassed approximately $83 million in revenue over five years, according to a legal filing.

Court papers, including divorce filings, show Daniel Koetting enjoying a lavish lifestyle in recent years, living in a five-bedroom, five-bath house in La Jolla, an affluent seaside enclave of San Diego. He owned thoroughbred horses, drove a Porsche and dabbled in motion pictures. He and his wife had three children. In the divorce, he reported household expenses in 2021 that included an average of $7,000 a month on groceries and eating out, plus an additional $5,000 a month for “entertainment, gifts and vacation.”

Daniel and Mark Koetting did not reply to emails, calls or letters from ProPublica seeking comment.

Meanwhile, the two companies that RIVO and LDF run — Evergreen Services and Bridge Lending Solutions — are associated with more than 200 complaints from customers since 2019, frequently about onerous interest rates and payment terms. “I just don’t understand how people can do this,” a California resident protested to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. “This is a predatory lender and I am a victim.”

Early on in LDF’s leap into lending, the large building on the corner of this shopping center housed a call center above a smoke shop. (Credit: Tim Gruber for ProPublica)

Early on in LDF’s leap into lending, the large building on the corner of this shopping center housed a call center above a smoke shop. (Credit: Tim Gruber for ProPublica)

Bildsten, the former Wisconsin department head, believes that LDF tribal leaders are trying to help the reservation improve services, such as dental care, for its members and that the lending business is part of that laudable goal.

“They’re able to do some good stuff,” Bildsten said, “but the money is dirty.”

An Ill-Fated Loan With Profound Ramifications

Brian Coughlin lit a cigar. Sitting in his Chevy Malibu with the sunroof open to let out the smoke and a bottle of pills next to him, he wondered: When will this end?

He’d faced many hurdles in life, from serious physical and mental health issues to the loss of his father. He’d also used bad judgment, overspending and loading up on multiple credit cards as he blew through a decent paycheck as head of trash collection for the city of Boston.

Like many other Americans with little to no savings and poor credit scores, he was enticed by online pitches for quick cash — offers that came with exorbitantly high interest rates.

Months earlier, in December 2019, he’d filed for bankruptcy, expecting relief. There would be payment plans and a court injunction halting contact from creditors — a key protection laid out in U.S. bankruptcy law. But one creditor would not give up.

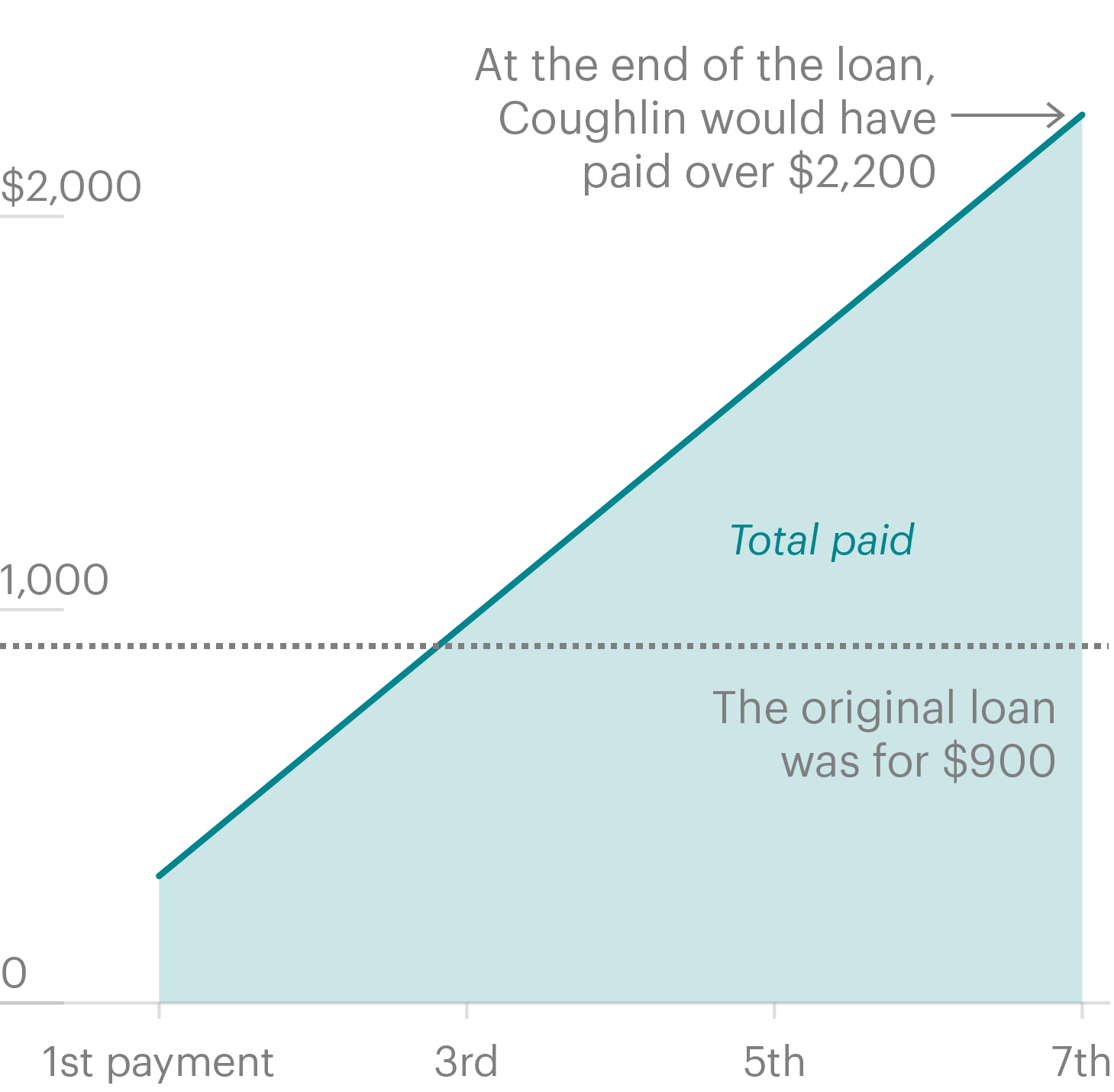

Lendgreen, one of LDF’s initial companies, had loaned Coughlin $900 at an annual percentage rate of 741%. At the time of the bankruptcy, he owed $1,595. The company continued to call, email and text him, fueling his anxiety. A phone log shows Lendgreen called Coughlin 50 times during one four-month period.

Brian Coughlin's Three-Month Loan Came With a 741% APR

Source: Brian Coughlin’s loan agreement. (Credit:Lucas Waldron/ProPublica)

Source: Brian Coughlin’s loan agreement. (Credit:Lucas Waldron/ProPublica)

“This is all for nothing,” Coughlin recalls thinking of the bankruptcy process.

That night in his Chevy, Coughlin took a fistful of pills and ended up in the hospital. Lendgreen still was calling him while he recovered. But now he was ready to fight.

Coughlin’s attorney filed a motion with the bankruptcy court in March 2020 asking a judge to order Lendgreen, the LDF tribe and LDF Business Development Corporation to stop harassing him.

The case was about more than just harassment, however. Coughlin wanted compensation for all that had happened. He asked the court to award him attorneys fees, medical costs, expenses for lost time from work while hospitalized and punitive damages.

Coughlin (Credit: Bob Croslin for ProPublica)

Coughlin (Credit: Bob Croslin for ProPublica)

To Coughlin’s surprise, LDF told the court that sovereign immunity protected it even in a federal bankruptcy case, and the bankruptcy judge in Massachusetts agreed. When Coughlin took the case to the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and won, the tribe appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

As they dug into who actually violated the collections ban, Coughlin’s attorneys needed to unravel the business relationships surrounding Lendgreen, which no longer has an active website. That led them on an international paper chase from Wisconsin to Ontario, Latvia and Malta, an island in the Mediterranean, where an entity that provided capital for Lendgreen appeared to be based.

In gathering evidence, Coughlin’s lawyers obtained an agreement between Lendgreen and another company — Vivus Servicing Ltd. of Canada — showing Vivus was to handle most all operations of issuing and collecting the loans made in Lendgreen’s name. It also would retain most of the profits.

For each new or renewed loan, the contract called for Vivus to share $3.25 with LDF as well as $3.25 per loan payment, or not less than $10,000 a month.

Vivus Servicing had subcontracted certain administrative functions of the Lendgreen loans to 4finance Canada, an affiliate company of a European lending conglomerate based in Latvia, court records show. An attorney who represents Vivus and 4finance declined to comment.

“There’s money flowing to all sorts of places,” Coughlin’s attorney Richard Gottlieb said.

As he began to better understand the web of connections, Gottlieb concluded that LDF’s role in its lending operations was minimal. The partners, he said, performed all the key functions — “from the creation of the loans themselves to the maintenance of the computer software and internet sites to the collections personnel to the customer service reps to the management.”

Even though LDF fought in court to be able to pursue collections against people in bankruptcy, internal documents indicate that the head of LDF Holdings, which oversees the tribe’s lending enterprise, was not pleased with how a business partner treated Coughlin.

Jessi Lorenzo, president of LDF Holdings at the time, communicated in May 2020 with 4finance Canada about Coughlin’s loan. Why had they not stopped soliciting repayment once notified that Coughlin had filed for bankruptcy, she asked in an email.

“Everything should have ceased then,” wrote Lorenzo, who was based in Tampa.

In a brief interview on her porch, Lorenzo declined to comment on the Coughlin case and said she did not want to be part of a tribal lending story that might be negative. Later, in an email, she wrote that she was proud to have worked for LDF as it “built a business that benefited their community, providing modern careers with upward mobility and good benefits in a remote part of Wisconsin.”

A Future Clouded by Legal Challenges

LDF tribal leaders don’t talk much about their business with outsiders. But there is little doubt that the lending business has altered the shape of the tribe’s finances, allowing LDF to move past its costly mistake of issuing $50 million in bonds for the Mississippi casino boat.

The Tribal Council agreed in 2017 to pay $4 million and finance an additional $23 million to settle claims against it after defaulting.

But the tribe and its partners continue to face new threats from a range of legal actions.

The attorneys in the Virginia case have promised future litigation against more LDF partners. And as LDF keeps lending, it opens its companies up to additional consumer lawsuits. Dozens of such cases have been filed since 2019, most of which end quickly, with undisclosed settlements.

McFarland takes issue with these types of cases against tribes. “The law firms filing class action lawsuits seek to paint tribes as either victims or villains in online lending,” he said in an email. “This approach has been employed against tribes since Europeans came to the Americas, whether Tribes are entering gaming, cannabis, selling tobacco, and a host of business opportunities.”

When Coughlin’s suit reached the Supreme Court, some of the issues involving tribal-lending partnerships were touched on, if only briefly.

During a hearing in April 2023, Justice Samuel Alito interrupted LDF’s lawyer as he was talking about sovereign immunity and the Constitutional Convention. Alito inquired about the tribe’s relationship with Lendgreen.

“Who actually operates this?” he asked.

“The tribe does, Your Honor,” replied attorney Pratik Shah, representing LDF. “This is not a rent-a-tribe situation.”

Shah said the enterprise employed 50 to 60 people working out of a headquarters on the reservation, though “they use third-party vendors, servicers and all, like any other business.”

Shah added: “This is a fully tribal operation.”

But the central issue was whether the tribe could be held liable for violating bankruptcy rules.

“What the tribe is saying is you can’t sue them for hundreds of thousands of dollars of actual damages,” Shah told the court. “That’s at the core of sovereign immunity.”

In June of last year, the high court sided with Coughlin, ruling 8-1 that there’s no sovereign immunity for tribes when it comes to the Bankruptcy Code.

Justice Clarence Thomas concurred in the ruling, not because of his reading of the Bankruptcy Code, but because he held that sovereign immunity does not apply to lawsuits arising from a tribe’s commercial activity conducted off-reservation.

Coughlin, far left, in front of the Supreme Court with his attorneys Terrie Harman, Richard Gottlieb, Gregory Rapawy and Matthew Drecun (Credit:Courtesy of Richard Gottlieb)

Coughlin, far left, in front of the Supreme Court with his attorneys Terrie Harman, Richard Gottlieb, Gregory Rapawy and Matthew Drecun (Credit:Courtesy of Richard Gottlieb)

Back in Bankruptcy Court, Coughlin continued to pursue LDF and Lendgreen for damages and legal fees. In mid-August, in the midst of settlement talks, Coughlin asked the court to pause the process required to unmask the outside entities involved with LDF as all sides tried to resolve the dispute. In September, a judge approved a settlement in which the tribe and Lendgreen agreed to pay Coughlin $340,000. LDF denied liability as part of the agreement.

At the same time, pressure is mounting on the tribe’s business partners. As part of the deal, the tribe will give Coughlin documents “with respect to the culpability and responsibility” of the outside partners, according to the settlement. That will enable Coughlin’s lawyers to dig further. LDF also will make a corporate representative available to testify in legal actions against their former business allies, if necessary.

“I want to see all the actors that are actually part of this scheme brought to justice, in a way,” said Coughlin, who now lives in Florida.

“I don’t necessarily believe the tribe is the orchestrator of this whole mess. I think they’re a pawn, unfortunately.”

_______________________

To do the best, most comprehensive reporting on this opaque industry, ProPublica wants to hear from more of the people who know it best. Do you work for a tribal lending operation, either on a reservation or for an outside business partner? Do you belong to a tribe that participates in this lending or one that has rejected the industry? Are you a regulator or lawyer dealing with these issues? Have you borrowed from a tribal lender? All perspectives matter to us. Please get in touch with Megan O’Matz at [email protected] or 954-873-7576, or Joel Jacobs at [email protected] or 917-512-0297. Visit propublica.org/tips for information on secure communication channels.

_______________________

Mariam Elba contributed research.

Joel Jacobs is a data reporter at ProPublica.