- Details

- By Mark Fogarty, Guest Opinion

- Opinion | Op-Ed

Opinion. Community development financial institutions (CDFIs) are a logical candidate to help tribes increase access to capital for carbon-dioxide removal and greenhouse-gas reduction, as there are currently dozens of them in place and they have access to several funding sources. But they tend to be on the small side, suggesting that a hybrid encompassing another type of financial institution may help.

An intriguing model is a combination Native CDFI / Native CDE (Community Development Entity).

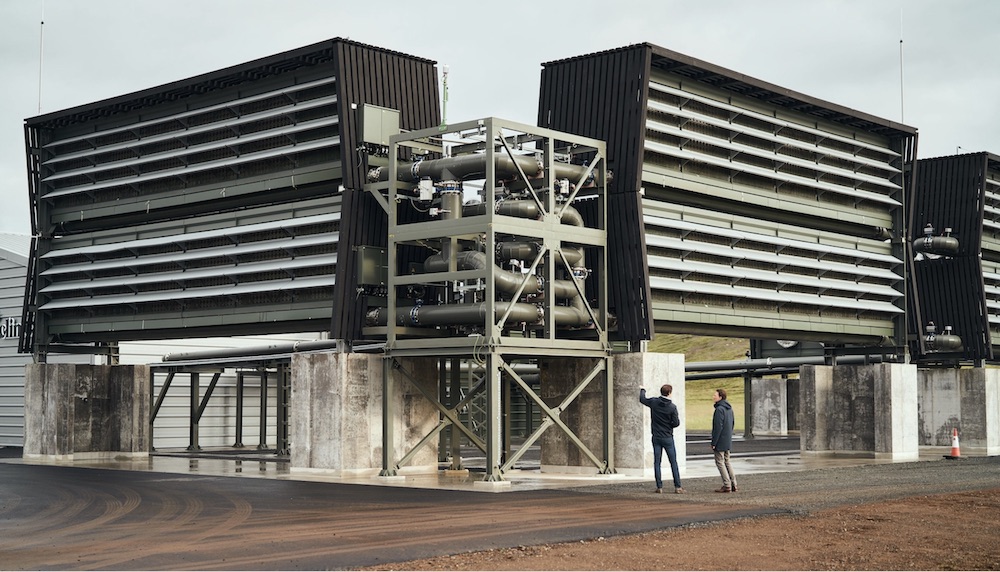

Tribal leaders I have talked to privately seem ready to take on carbon removal in a big way, and some already have. The Upper Nicola Indian Band, a First Nations community in British Columbia, has announced it wants to provide the land for and be a partner in a $1.3 billion direct air-capture facility planned to be built on one of their reserves, an example of the “scientific” approach to CO2 removal. On the “natural” side, the Tulalip Tribes of Washington state plan to generate hydrogen fuel, gain carbon credits, and sequester carbon by a biogas process.

CDFIs, including Native CDFIs which have their own category and funding, are local financial institutions intended to work in underfunded areas. These groups, which are loan funds but not depository institutions, are incubated and financed by the U.S. Treasury Department’s CDFI Fund, which commenced funding them in 1996. While they tend to be small, in aggregate they can be powerful.

In April, 29 Native CDFIs received $47 million from the CDFI Fund to help low- and moderate-income populations recover from the economic devastation of the COVID pandemic. The grants ranged from $500,000 to $6.1 million and were part of an overall disbursement of $1.7 billion to 600 CDFIs, both Native and non-Native. Native CDFIs also have received $17 million this year via their own CDFI portal, Native American CDFI Assistance (NACA), for a total of $64 million.

This aggregate amount suggests that a coalition of Native CDFIs may be necessary to tap sufficient capital for carbon projects. Two coalitions already exist—the Native CDFI Network, which has more than 60 members, and the Oweesta Corp., an “intermediary” CDFI which funds a network of about 25 Native CDFIs. Partnering with these groups, or establishing a stand-alone coalition for carbon removal, would be one way to go.

In addition to funding ongoing operations (and the Native CDFIs are free to leverage that money through foundations and other funders), the CDFI Fund incubates new Native CDFIs through technical assistance awards, which could be a key part of bringing individual tribes up to speed on carbon removal.

The CDFI Fund also runs a bond-guarantee fund for projects of $100 million or more. It has guaranteed 21 such projects to date, though it is unclear if any of them are with Native groups. Natives are at a disadvantage when it comes to municipal bond finance, as they are limited to bond finance only for “essential government functions,” which means other methods of capital-market finance, such as blockchain, need to be looked into as well.

Foundation money likely would be available to tap for trial carbon-removal efforts. The Kellogg Foundation, for instance, targets Native groups for grants. A somewhat smaller group, the Northwest Area Foundation, has committed that at least 40% of its awards will go to Native-led groups for the next decade. It also has a specific interest in funding Native CDFIs, which means it could be a source of funding and energy for the kind of institution this roadmap envisions.

New Markets Tax Fund and Native CDFIs

In addition to the CDFI Fund, though, Native CDFIs have access to another governmental source of funding—tax credits. The major ones are the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), which could come into play when tribes develop robust carbon-removal economic-development efforts that make it desirable to develop housing for workers in this new economy, and the New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC), which can be valuable to Native CDFIs right now. It is targeted to business lending, which makes it directly on point for tribal carbon efforts. It is administered by the CDFI Fund.

It is definitely possible to double-dip from both the CDFI Fund’s programs and from the New Markets Tax Credit. But very few Native CDFIs have done so. That requires getting a separate designation beyond a CDFI certification: a CDE, or Community Development Entity designation. One Native CDFI that has pursued both forms of finance, Alaska Capital Growth BIDCO of Anchorage, has received $10 million from the CDFI Fund over the years and $90 million in New Markets Tax Credits. (A BIDCO is a Business and Industrial Development Corp., a loan fund not unlike a CDFI.) It has used this money to finance projects for things like broadband and community facilities in remote Alaska Native villages.

This model may prove to be a potent combination for tribal carbon-removal efforts. There is one major, though technical, difference between the Low Income Housing Tax Credit and the New Markets Tax Credit. The NMTC is more efficient and more sovereignty-friendly.

The LIHTC is administered by state housing-finance agencies. They hold competitions for awards for projects submitted by developers, which are rated according to a points system. Once the state agency makes an award to a developer, a developer hires a capital-market specialist, called a syndicator, to find investors for the tax credits. Companies looking for Community Reinvestment Act credit, like banks and insurance companies, are typical investors.

But on the NMTC side, the syndicators are eliminated. The NMTC awardee becomes in effect, both the developer of the project and the syndicator, finding the investors for the project. This is more efficient, as it eliminates the syndicators’ fee, and also more sovereignty-friendly, as tribes who develop carbon-removal operations will have the main say in these elaborate financial transactions.

An Indigenous CDFI-CDE would have access to a lot of capital and a lot of leeway in how it uses it, making it a model that should be studied carefully for this effort.

One drawback is that these types of government financing generally cannot be used internationally. Therefore, a similar mechanism must be found, or invented, for international Indigenous efforts at carbon removal and greenhouse-gas reduction. It seems quite possible, though, that a “holding company” type structure could hold both national and international effort within one venture. Such a structure would also allow the I-CDFI to oversee coalitions of separate tribal ventures in the carbon arena, providing technical assistance to help start them up and access to the capital they need once they are functional. Approaches like these will be examined in a subsequent essay.

Mark Fogarty is a former Tribal Business News contributing writer who has been covering tribal financial institutions for 30 years. This opinion piece was commissioned by Global Ocean Health, a Seattle-based organizer of the scientific, policy, and communications support tribes need to stand up for the sea that feeds an estimated 3 billion people. The essay is part of a research project to explore how tribes can finance their initiatives in carbon removal.