- Details

- By Chez Oxendine

- Real Estate

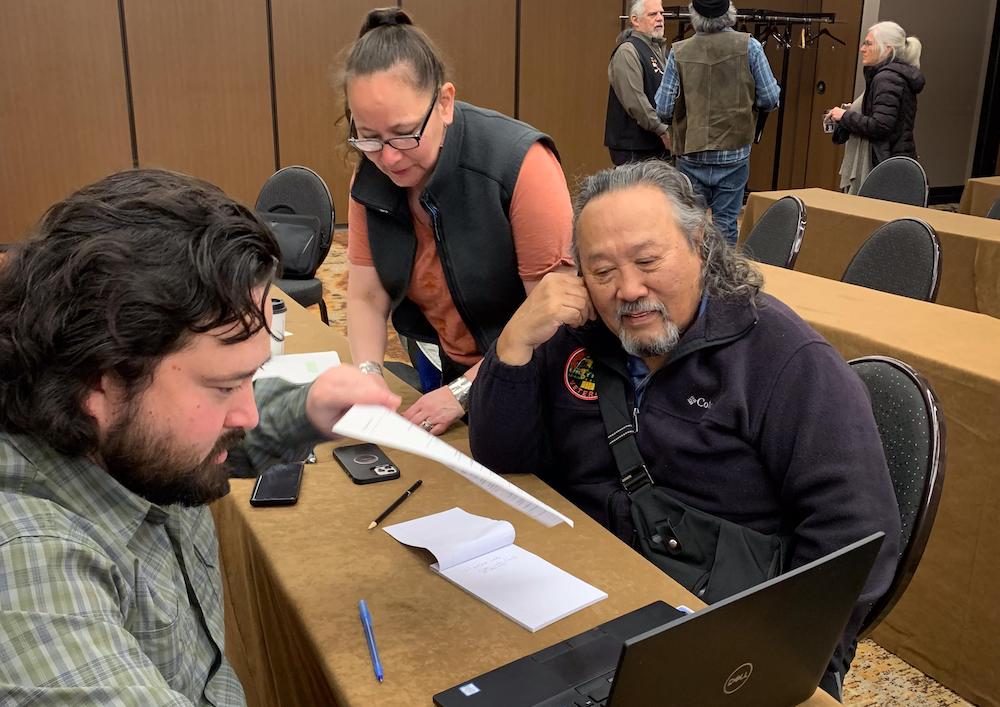

Mike Everett has helped allocate thousands of acres of Alaskan wilderness to Alaska Native veterans who missed their chance at land ownership while serving during the Vietnam War.

Everett, a land law examiner for the federal Bureau of Land Management, has seen the Native veterans use the land for everything from moose camps to cabins, though very few of them turn the often-inaccessible parcels into permanent residences.

What he sees more often, however, is a desire for legacy: a place to leave for their children and grandchildren.

"I would say one of the biggest sentiments that we're getting from this program is a lot of the applicants want to see their family receive land that they can use down the road," Everett told Tribal Business News. "All the veterans we're serving are in their late 70s, early 80s — they're more focused on what they can leave behind for their family."

The 2019 law in question is the John D. Dingell Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act. That act established the Alaska Native Vietnam-era Veteran Land Allotment Program (ANVLAP), which aims to give land to Alaska Native veterans who were out of the country during land allocations in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Each applicant or applicant's heir can receive up to 160 acres — an area roughly the size of 120 football fields — carved from a portion of BLM's managed lands in Alaska. In late November, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland signed Public Land Order 7952, adding 11.1 million acres of public lands in central Alaska to the program, bringing the total available land to 39 million acres.

The BLM has identified 1,900 Alaska Native veterans who served between 1964 and 1971 as potentially eligible for the program. While many of the eligible applicants have been located and contacted by the agency, they are still looking for roughly 150 veterans whose information they cannot locate, according to ANVLAP Director Erika Reed. (Anyone with information on those veterans is encouraged to contact Everett at [email protected]. )

With many eligible veterans now in their 80s, the BLM has set a firm deadline of Dec. 29, 2025, for veterans or their families to apply.

Allocating a further 11 million acres follows a recommendation from the bureau as part of the recently finalized Central Yukon Resource Management Plan. The lands were opened by partially revoking certain federal land withdrawals under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

"The Alaska Native veterans that served our country deserve our service in return, which is why our Dingell Act work has been a top priority for us," BLM Alaska State Director Steve Cohn said in a statement. "I'm proud to announce this public land order that expands the acreage available to these veterans and hope this encourages more veterans to apply for their allotments."

A Unique Program

This land allotment program is special because it doesn't require proof of use or occupancy, unlike previous allotments. This means more veterans should be able to successfully apply for the conveyance, according to the BLM press release.

Reed said the program emerged from an intersection of prior laws around Alaska land allocations. She pointed to the Native Allotment Act of 1906, which sought to create individual allotments out of some reservation lands throughout the U.S. Since Alaska didn't have much in the way of reservation lands, they received their own law, the Alaska Native Allotment Act.

However, muddled communications around the law led to very few claims on the land in question. In addition, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act abolished many aboriginal land titles in 1971, closing the window on allotments — just as applications for those allotments were reaching a fever pitch. Reed noted that out of 16,000 applications under the Alaska Native Allotment Act, 11,000 were received between 1970 and 1971.

Outcry was raised about the inability of Alaska Natives serving in the military during the Vietnam War to apply for these lands. Not every veteran was in direct combat in Vietnam — some served in other theaters, such as bases in Europe — but they were out of the country when allocations really got underway.

Eventually, the initial version of ANVLAP was authorized in 1998 by Congress — but included onerous use and occupancy requirements, as well as a very tight window of eligibility between 1969 and 1971.

That first wave of responses in 1998 included about 1,000 applications but only distributed 300 certificates because of those requirements, Reed said. The 2019 version of ANVLAP has since attempted to alleviate those issues, lifting the requirements and extending the window between 1964 and 1971.

"The veterans groups were still unhappy because they felt that the limited opening period for service didn't reflect the full scope of the Vietnam campaign," Reed said. "What this program does is try to recognize a broader window of service."

As for the future of the program, that depends on Congress, Reed said. The Fish and Wildlife Service has submitted a report to Congress recommending a further 3.6 million acres be added to the program, but that will require legislative action rather than departmental approval.

It's important to open more lands for selection so that applicants have a wider range of choices for their allotment — particularly lands close to their home territories or nearer communities, Reed said.

Most available lands require bush plan or boat access, often lying hundreds of miles from the nearest road or community, according to Reed.

"BLM managed lands are largely not near communities, nor road accessible, so many people have not been satisfied with the lands that are available," Reed said. "We are hoping that Congress will be able to open up the additional lands, such as parts of refuges in the National Wildlife Refuge System."

As Congress considers whether to further expand the program, the bureau's focus remains on finding those last 150 applicants. With most eligible veterans in their late 70s and 80s, Reed emphasized the urgency of the program.

"Those veterans shouldn't miss out on this opportunity because they were serving their country," Reed said. "We want to make sure that they know about the chance to apply for this land."