- Details

- By Elyse Wild

- Sovereignty

NORTH BEND, Ore. — The Coquille Indian Tribe has penned a historic agreement with Oregon state leaders to co-manage fish and wildlife in the state’s southwest region.

Last month, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) Commission voted unanimously to approve an agreement to give the tribe power to manage fish and wildlife in the Coquille River watershed.

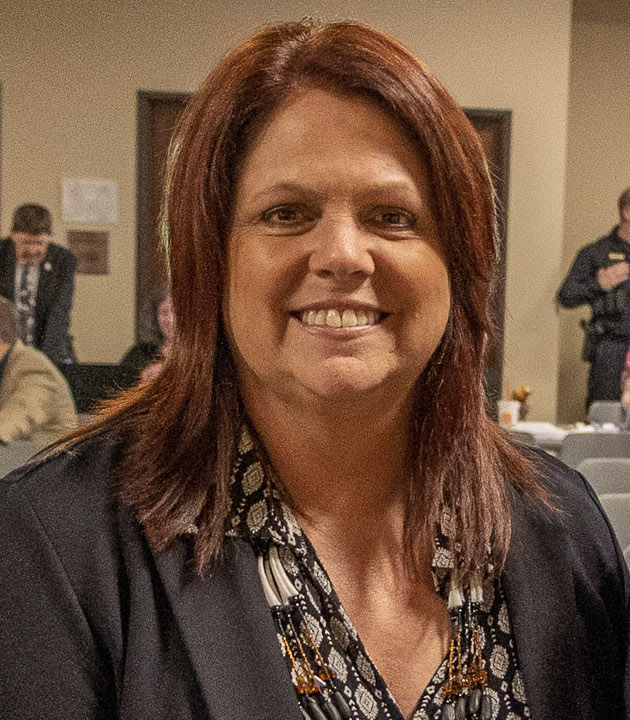

Brenda Meade, chair of the Coquille Indian Tribe. (Photo courtesy of ODFW)“I feel almost in awe because we aren’t done yet,” Coquille Tribal Chair Brenda Meade told Tribal Business News. “This is just the beginning.”

Brenda Meade, chair of the Coquille Indian Tribe. (Photo courtesy of ODFW)“I feel almost in awe because we aren’t done yet,” Coquille Tribal Chair Brenda Meade told Tribal Business News. “This is just the beginning.”

The tribe is hailing the agreement as a win for tribal sovereignty because it enables the tribe to fulfill their sacred duty to be stewards of the watershed. Moving forward, the tribe and the state will work together to determine management activities within a five-county area and allocate resources toward such activities to achieve the best outcomes for fish and wildlife. Under the agreement, tribal members also have the ability to hunt, fish and trap under the authority of the tribe, as opposed to having to buy a license from ODFW.

“We are very excited about it,” said Davia Palmeri, conservation policy coordinator at ODFW who served as the primary negotiator of the agreement. “The restoration of hunting, fishing and trapping for tribal members is a really important piece of the state’s overall effort to make progress between the state and the tribe.”

The impetus for the agreement stemmed from the potential loss of Chinook salmon, a natural resource sacred to the Coquille. In May 2021, the ODFW reported extremely low returns of Chinook in the Coquille River. From sustenance to cultural practices, the large salmon are integral to Coquille life.

Chinook have all but disappeared from the river. In 2010, more than 30,000 returned to spawn in the fall, but the numbers have dwindled to merely a few hundred. While salmon levels were low enough in 2020 to close the river to fishing, the tribe didn’t fully understand how close the species was to extinction.

Meade told Tribal Business News that the Coquille River has the lowest returns of salmon in the state, with the rapid decline driven by invasive species like smallmouth bass and striped bass, which depletes the river of natural resources salmon rely on. She describes feeling devastated as the tribe contemplated the loss of the Chinook.

“These are our ancestral homelands,” Meade said. “How can we uphold our traditions and our ceremonies without the salmon in the river? I can’t even contemplate that world.”

The tribe issued an emergency declaration in August 2021 and after consulting with ODFW, determined the state’s response would be insufficient to save the salmon in the Coquille.

“It felt like it hit so fast,” Meade said. “We have been so knee-deep in the pandemic like everyone else. We went, ‘Oh my gosh, we haven’t been paying attention.’”

The Coquille River runs 36 miles through southwest Oregon, draining more than 1,000 square miles of the Southern Oregon Coast Range into the Pacific. Its watershed is 1,089 miles long. Oregon has 114,000 miles of river snaking through its landscape, all of which are overseen by ODFW through a regional management structure.

“We recognized that they were struggling with boots on the ground and they are spread thin,” Meade said. “As a tribal council, we recognized the state could not do it by themselves, and we can’t do it by ourselves.”

While the framework for the agreement received overwhelming support, some public comments opposed it, citing prioritizing tribal members over non-tribal members. However, public comment received on June 15 included a letter of support from Oregon Gov. Kate Brown, who wrote: “As we engage in the difficult work of dismantling systems of racism and colonialism, we must work together to find innovative ways to create a just and equitable Oregon.”

Fellow Oregon tribes, including the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe and Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians, also issued comments of support, along with surrounding municipalities such as the City of Myrtle Point, the City of Coquille, the City of Powers and more.

“Our entire community is coming together,” Meade said. “This is important to all of us. We have such great support.”

While the official agreement formalizes the conservation collaboration between the tribe and the state, the two worked together last year to address the Chinook salmon crisis. The results offer a promising glimpse into the future. In 2021, the tribe, along with ODFW staff and volunteers, collected 24 breeding pairs of chinook from the hatchery system — a 700 percent increase from the year prior when ODFW managed collection alone. Last month, they released 1,000 salmon smolts that came from those eggs back into the river system.

Path forward

Meade hopes her tribe’s agreement can serve as a canvas for the state’s eight other tribes in negotiating mutually beneficial terms with the state in a way that also acts as cultural preservation.

“This is a path forward,” Meade said. “This is sovereignty. We are working together for the common good.”

In November 2021, Congress introduced legislation that would reopen the negotiation of Oregon’s hunting and fishing authority over the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians and the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde. The tribes’ rights to hunting and fishing on their own lands were restricted in the 1980s as terms of an agreement to regain federal recognition.

“We hope that we can do more of this proactive and collaborative work with all of Oregon’s tribes,” Palmeri said.