- Details

- By Elyse Wild

- Sovereignty

A new report from the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development aims to provide a comprehensive starting point for both tribes and state governments in outlining a clear path for landback.

The policy brief discusses how geographic information systems can drive landback opportunities forward.

With varying tribal and local government relationships, Indian Country has no one-size-fits-all approach to landback agreements. However, landback and co-management opportunities have begun to accelerate recently.

In the past six months alone, the Bois Forte Band received 28,000 acres of its land back in northern Minnesota, the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa finalized the return of more than 1,500 acres of land along the shoreline of Lake Superior, and the city of Oakland announced a plan to return a portion of city land to Indigenous stewardship.

Laura Taylor, who co-authored the “Considerations for Federal and State Landback” policy brief, spoke with Tribal Business News about finding “win-win” solutions and how state land checkered through reservations inhibits economic and cultural growth.

Tell me about the process of researching and writing this policy brief.

We’ve been working on this policy and other things having to do with the plan with the Harvard Project for the past year. We’ve been convening and trying to gather information and put some architecture around this landback movement. When I say architecture, I mean for policy purposes.

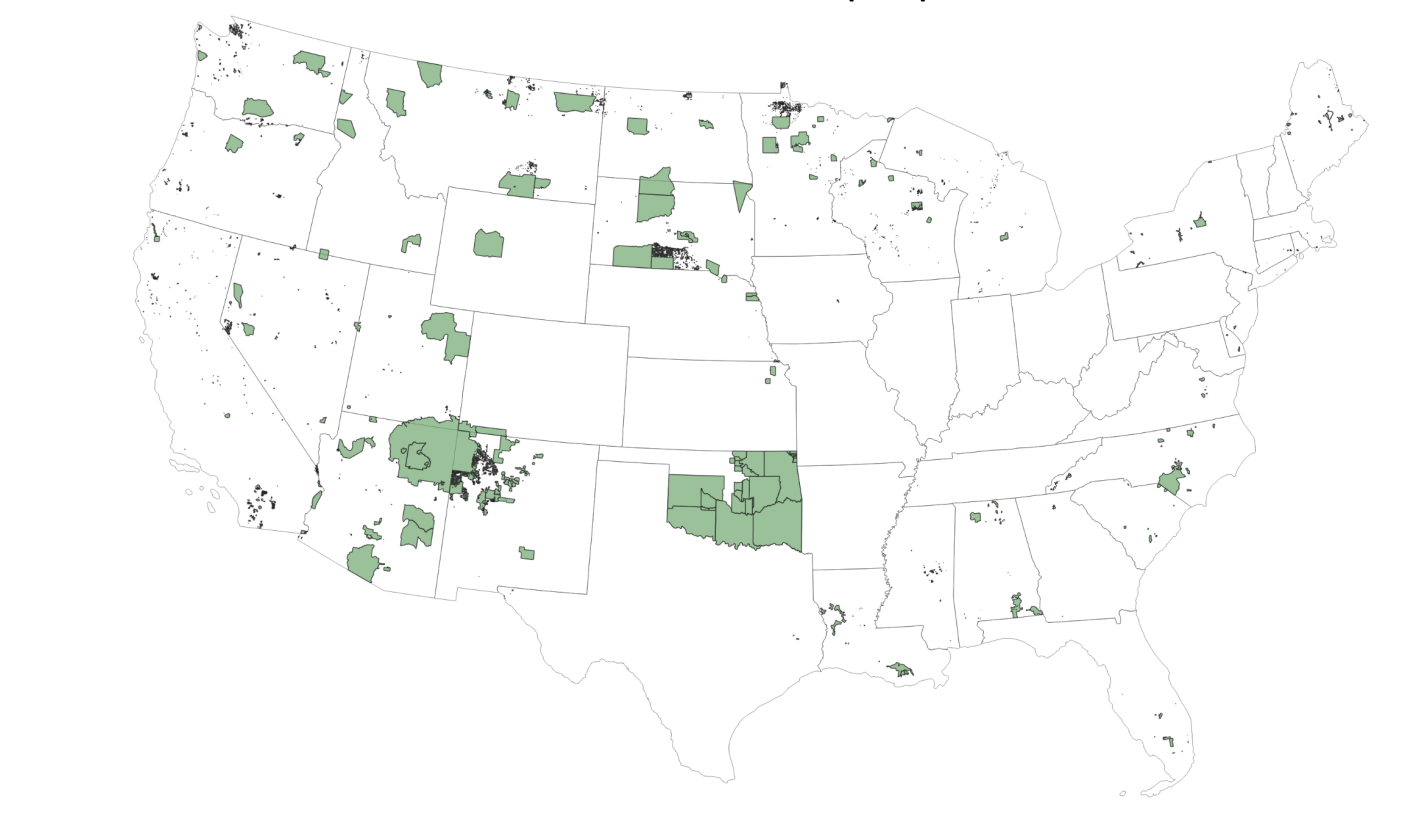

As part of my dissertation effort, I’ve collected, digitized and mapped a lot of information. Once you have something on a map, you can connect it to a lot of other things. This policy brief evolved from wanting to know some very baseline information. If a large portion of these reservations were supposedly lost to Western encroachment or pushed by the U.S. government, what is that land doing now? A map helps to condense information to put it out there. That started the process of putting forth a policy brief that would be digestible with important pieces of history and ideas condensed really into a picture.

Being digestible is important since landback can be complicated and challenging for people to understand. While we are seeing more co-management and landback agreements, there is no one set process for tribes to pursue it. Do you envision the information in this policy making the process easier or more accessible?

Right, the process is so varied. When we first approached the topic of landback, we didn’t realize how complicated it was until we got into it. Another policy brief we’ll be putting out soon is a framing paper on how to think about the spectrum of landback. Again, not that we’re defining it, but we’ve listened to what other practitioners are doing. We are trying to bring it into one paper to have a language to talk about it for practitioners, tribes and the government.

pre-doctoral fellow with the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development Laura Taylor. (courtesy photo)

pre-doctoral fellow with the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development Laura Taylor. (courtesy photo)

How can the information in the brief be beneficial to tribal governments?

We’re collecting a database of examples of successful landback so that people can really understand how it happens. It varies, too, on what tribes’ goals are. Some tribes have management or jurisdictional goals or want space to practice culture. Other tribes might want that full fee-to-trust process. Those are all very different goals. We thought even just understanding the federal government may or may not be amenable to a land transfer or management agreement, having salient information of, ‘This is U.S. forest land, and it’s empty and on historic reservation land for this tribe: Why can’t this be in the conversation?’ That’s powerful information. We saw this policy brief as a collection of low-hanging fruit. Whether you’re on the tribe side or the government side, it’s informative and powerful to say, ‘Oh, wait a minute: I didn’t know that.’

In the government, some people might not know that there was such a diminishment of reservation land. They might not know that some of that land is currently parks or that there’s state land checkered throughout the reservations.One thing, especially with the state land, is that we talk about this in the policy brief, but in terms of trying to wade through the very arduous process of engaging in any of this, there are clearly some win-win solutions. For example, in some states, it’s hard for them to have land in the middle of reservations. Those could be areas where if tribes have access to these maps, they can start the conversation with those state governments.

From an economic standpoint, how could this spur economic development for tribes as they expand their landholdings?

It really depends on what the tribe is looking for. You can think about this from a very broad sense. In the paper, we don’t have data to say, ‘This is causing this.’ But you can think of it in the sense of nation-building: Having a place to exercise sovereignty and cultural practices brings positive benefits for tribes. And, of course, land ownership is typically a way in our society now that relates to wealth and economic development in some ways. But in other ways, even just management agreements or recognition significantly impact the sovereignty part of socio-economic building.

Landback is a complicated issue, and unless people take the time to educate themselves about it, it can sound like non-Indigenous communities are losing something in the process, but that isn’t the case.

Most people who are not necessarily connected to this history or to tribes today don’t understand that a lot of like federally defined protected land was just taken from the reservations. On the one hand, it’s valuable to show that, and on the other hand, it’s valuable to show that a lot of areas within that are potentially available to be put back in there. Once you think about it, there’s not really a reason why it shouldn’t be.