- Details

- By Chez Oxendine

- Sovereignty

For many years, tribal sovereignty concerned itself primarily with the governance and control of natural resources, says Delaware Tribe of Indians citizen Maranda Compton.

In the modern era, though, that definition has evolved to include digital assets, Compton said during a data webinar last week by the Center for Indian Country Development (CICD) at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. The entire concept has gone from a discussion of land and usage rights to something more modern, digital, and immediate, Compton said.

“When we talk about data sovereignty … it necessarily makes people realize that our sovereignty is not something that's just in history books and not something that's just in a land acknowledgement that references hundreds of years ago,” Compton said during the panel. “Our sovereignty is today. It's right now. And it's worth paying attention to.”

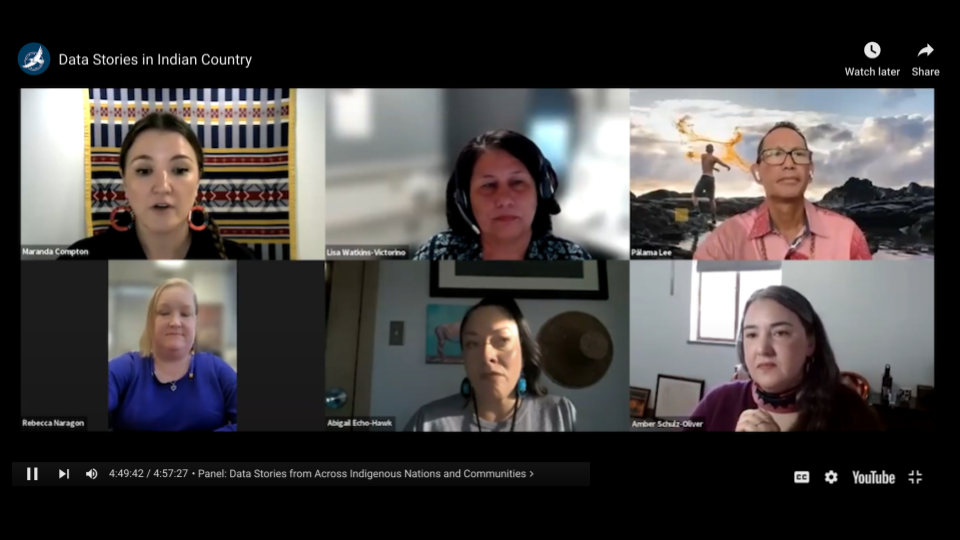

The panel on “Data Stories from Across Indigenous Nations and Communities” was part of a 5-hour online event featuring nearly two dozen speakers who are working to address the widely acknowledged data gaps that have hindered Indian Country’s ability to spot and address ongoing economic hurdles.

Joining Compton, an attorney and the founder of Missoula, Mont..-based consultancy Lepwe Inc., on the panel were Abigail Echo-Hawk, a member of the Pawnee tribe and executive vice president at Seattle Indian Health Board; Palama Lee, a Native Hawaiian and director for the nonprofit Lili’uokalani Trust; Rebecca Naragon, a member of the Poarch Creek Band of Indians and economic development director for the United South and Eastern Tribes; and Lisa Watkins-Victorino, a Native Hawaiian and community partner for CICD.

For Echo-Hawk, whose Indigenous data work was recently spotlighted in the New York Times, the issue boils down to who gathers what data, what that data is eventually used for, and the goals of those doing the gathering. Are the data collectors, for example, more interested in Native solutions or Western problem solving?

“Too often we're talked about as a ‘problem to solve’ versus every single one of the answers that exist for the vitality in the brilliance of our communities,” Echo-Hawk said. “And data sovereignty is at the heart of it.”

Other panelists shared Echo-Hawk’s sentiments, speaking to control over traditional knowledge and economic data as crucial elements of data sovereignty.

Because of mishandling and mistrust, especially in the COVID-19 era, many “crucial conversations” around data weren’t happening, Poarch Creek’s Naragon said. Tribes have been forced to report data on themselves in order to receive grant funding, creating a “transactional” relationship with the federal government, Naragon said. That data should guide federal officials where to provide help, not to create a back-and-forth dependency, she said.

“When I think about data sovereignty, it’s supporting our tribal leaders and sharing that data should first be for the needs of the community and (also) for informed and better planning for project execution,” Naragon said.

Data sovereignty should support the nation-to-nation relationship between tribal nations and the federal government, especially as it relates to the latter’s trust responsibilities, she said. The sharing of tribal data should reflect a cooperative relationship rather than a “carrot-and-stick” proposition, Naragon said.

Data determines support

Speakers also talked about definitions of data sovereignty and their own personal experiences with data and how it affected their tribes and their work.

Compton pointed to the flood of recovery funding in the wake of COVID-19 and how the federal government misused tribal data to make allocations. She recalled sitting on Treasury calls about federal distributions and hearing that they were based on government-collected population data constructed by examining an Indian housing block-grants program.

Compton’s tribe doesn’t participate in that program, so their population size was listed as zero, minimizing their allocation.

“It was a real question of why didn't the Treasury go to tribes and say, ‘Hey, what’s your population?’ And when they did go to those tribes, why didn’t the tribes regularly have that information ready?” Compton said. “Why is it that when I go to search for how many citizens my tribe has, I have to go to Wikipedia? I don’t go to my tribal nation’s website. I started to have a lot of questions about why these data gaps exist.”

Those gaps have contributed to issues with housing, jobs, education — all areas of Indian life where resources are infrequently distributed and scarce when they are, Compton said.

“You start to see that data sovereignty and digital jurisdiction are these really fuzzy sounding concepts, (but) they underlie absolutely every single priority of any tribal nation,” Compton said. “You want more resources? All of that is underlined by, and dependent on, data.”

Many of those gaps stem from holes in community data-gathering, said Watkins-Victorino. She pointed to similar gaps for Native Hawaiians, and their eventual solution: the Native Hawaiian Data Portal, which took on the task of building what data Native Hawiians could get on themselves.

That data set wasn’t complete, of course, due to privacy concerns and gathering methods. At the moment, the data portal uses state and federal data in combination with locally gathered statistics to build their data sets. That revealed that Native Hawaiians were often aggregated with Pacific Islanders from other areas in the region, rather than as their own distinct demographic, which further muddied the waters, Watkins-Victorino said.

In turn that muddled data impacts Native Hawaiians’ seat at the proverbial decision-making table, Watkins-Victorino said. In the time since, the Native Hawaiian Data Portal has helped clarify some of that data through their own collection, such as surveys, Lili’uokalani Trust’s Lee said.

Getting data on Native Hawiaiians — from Native Hawaiians — can help make those stories and those issues clearer to everyone, Lee said.

“Where are the people? What are their assets and strengths? What are the stories their elders tell? What are their ceremonies around?” Lee said. “We analyze all that together. Everyone can touch that infographic or report because it really provides multiple ways of understand and seeing the top of the mountain, [so to speak.]”

The end result for better data, said Naragon, is better understanding of where the most resources are needed for important issues like better health outcomes or increased economic development for tribes. Having data that’s Indigenous-led and -gathered is even better.

“If we’re perpetuating this data, we can have this transactional change,” Naragon said. “We're really seeing tribal nations really taking ownership of how we can build our own intentionally Indigenous-led data sources.”

Echo-Hawk wrapped up the panel by asking Native partner organizations and federal agencies to look at Natives holistically, and to gather data accordingly. That includes permission and cooperation from tribes, rather than approaching it like a math problem, she said.

“We are not a problem to solve,” Echo-Hawk said. “We are all of the answers and we have to shift the narrative of data away from a deficit based on how we're not doing well in this area or that area.

“(We should be) looking at the inherent strengths and the resiliency of our ancestors who survived so that we could thrive. This is our opportunity to demand change, and we have to use our sovereignty to ensure that it happens.”