- Details

- By Chez Oxendine

- Arts and Culture

SULPHUR, Okla. — Chickasaw Nation-owned Mahota Textiles builds its identity on weaving Southeastern art into blankets, tote bags, pillows and other products.

The cultural influence even extends to the choice of fabric the company uses for its products.

“We’re a Southeastern tribe. Cotton was something we would have used from our ancestral lands,” Bethany McCord, business and development manager for Mahota Textiles, told Tribal Business News. “Most of our products are 100 percent cotton, and that’s significant to us.”

Since its inception, Mahota Textiles has established a storefront in its hometown and expanded into 30 locations across 10 states, including the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

The Sulphur, Okla.-based company began in 2018 primarily as an online business founded by Chickasaw artist Margaret Roach Wheeler, who wanted to see more art from Southeastern tribes at Native art shows and in Native shops.

“We started out in Chickasaw retail locations, using social media and online sales and slowly moved into museum gift shops,” McCord said. “Margaret, given her name and the notoriety she has as an artist, was able to get us into these shops. Once we were able to say we were in the Smithsonian, it snowballed from there.”

The company’s designs stem from traditional Chickasaw symbols and stories. Each year, Mahota Textiles chooses a Chickasaw artist to create a set of designs, then the company’s board chooses a design to create a new blanket featuring the artist’s work.

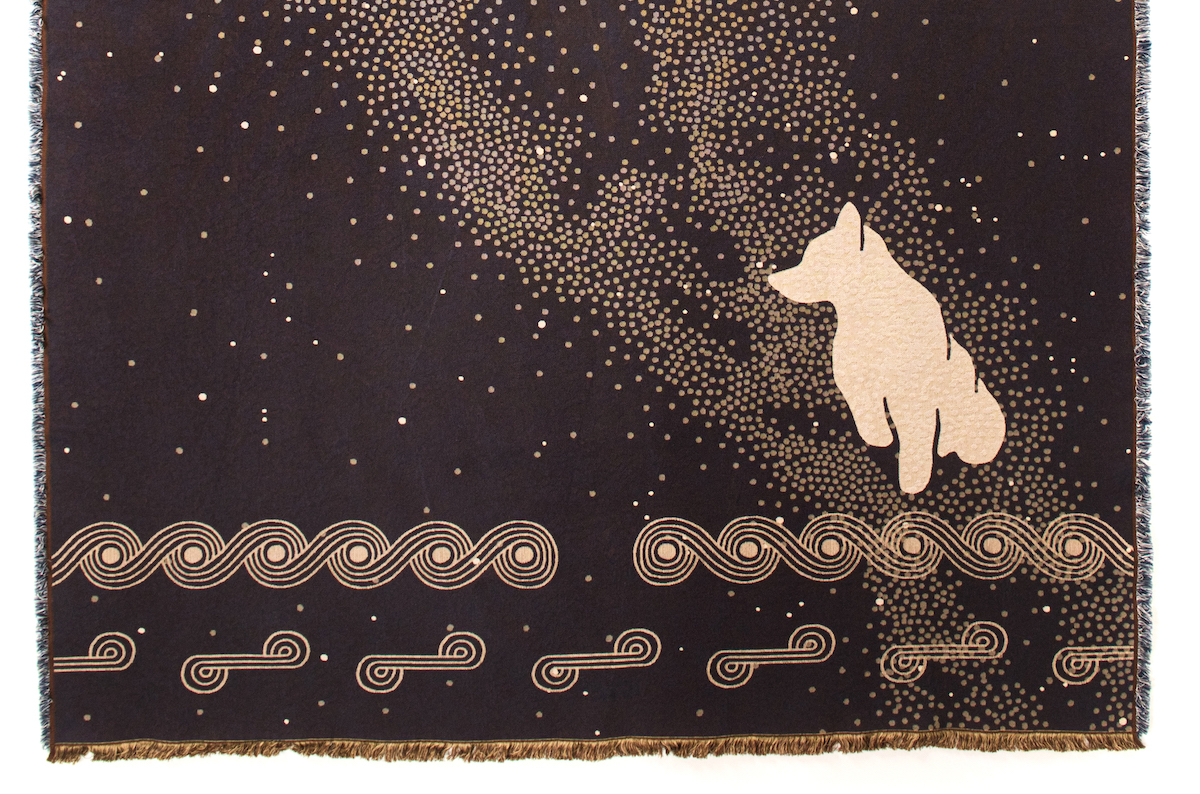

Chosen designs have included a pottery-themed blanket titled “Yaakni’ Chokma’ (Good Earth)” by Joanna Underwood-Blackburn, a depiction of the separation of the Chickasaw and Choctaw tribes called “Brothers’ Loss and Renewal” by Dustin Mater, and an interpretation of the Chickasaw belief in the afterlife, “The White Dog’s Path,” by Faithlyn Seawright.

Seawright’s design developed a special meaning in the wake of COVID-19, McCord said.

“(Seawright) did her take on the white dog, and basically how the Milky Way is used as the path that he would take deceased tribal members on,” McCord said. “One thing significant in her blanket was that she added stars. She made some brighter stars in her blanket representative of the Chickasaw elders we lost to COVID-19.”

Products featuring cultural symbols and stories important to the Chickasaw Nation also offer an effective way to teach both Native and non-Native people about the history and meaning behind the designs, McCord said.

She pointed to a recent experience at the Chickasaw Festival in early October, where visitors from across the country developed an interest in the symbolism.

“We had Chickasaw citizens from all over. A lot of them didn’t know the stories, or didn’t know why certain symbols or designs were significant. It was fun to just have them come to a booth and see the designs on our blankets and educate our own citizens,” McCord said. “They bought a blanket just because they had listened to their grandma or grandpa tell that story when they were younger. They wanted to take a piece of that home.”

Even non-Native visitors developed a connection to some of the products, which McCord interpreted as a sign that they’re a good way to share Chickasaw culture with everyone.

“It plays a significant role in teaching people about us,” she said. “It’s just been really neat to see that.”

Mahota Textiles operates within a $22.4 billion U.S. textile products industry that “saw a return to solid growth” in 2021 after a pandemic-related downturn in the prior year, according to a report from trade publication Textile World. As well, Mahota Textiles’ products also fit within the Native American art market, which the Southwest Association of American Indian Art and blockchain art registry Imprint valued at $1 billion, as Tribal Business News previously reported.

While the bulk of Mahota Textiles’ work focuses on cotton blankets and products, the company has been broadening its horizons by offering items in other fabrics, like silk. It’s also pushed into new businesses, such as providing upholstery services for the First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City.

“That was our first upholstery project, using durable fabric like nylon and polyester,” McCord said. “We’ve had a few of those special projects outside our normal business realm.”

McCord attributes Mahota Textiles’ success, and its survival during COVID-19 lockdowns that lowered foot traffic, to a successful social media strategy.

“Social media also helps any business in this day and age, but it’s been a really big help for us,” McCord said. “We were able to stay afloat and be business as usual during the pandemic.”

As for what’s ahead, Mahota Textiles aims to eventually create a warehouse space and expand beyond its current two employees, bringing shipping and production in-house. (Currently, the company designs its products in-house and uses U.S.-based partners to manufacture the blankets through computerized looms.)

McCord believes the company has a bright future ahead as it continues building its footprint online, in museums and beyond.

“We have a lot of support, a lot of backing, not only from our tribe but from other Native American organizations,” McCord said.