- Details

- By Chez Oxendine

- Indigenous Entrepreneurs

WINDOW ROCK, Ariz. — Roughly 70 percent of contracts on Navajo Nation go to non-Navajo businesses, which drags 70 cents out of every dollar the tribe spends off of the reservation.

That’s according to executives at the Dineh Chamber of Commerce, who say the tribe should be doing more to enforce the Navajo Business Operations Act, the purpose of which is to cycle dollars within the reservation.

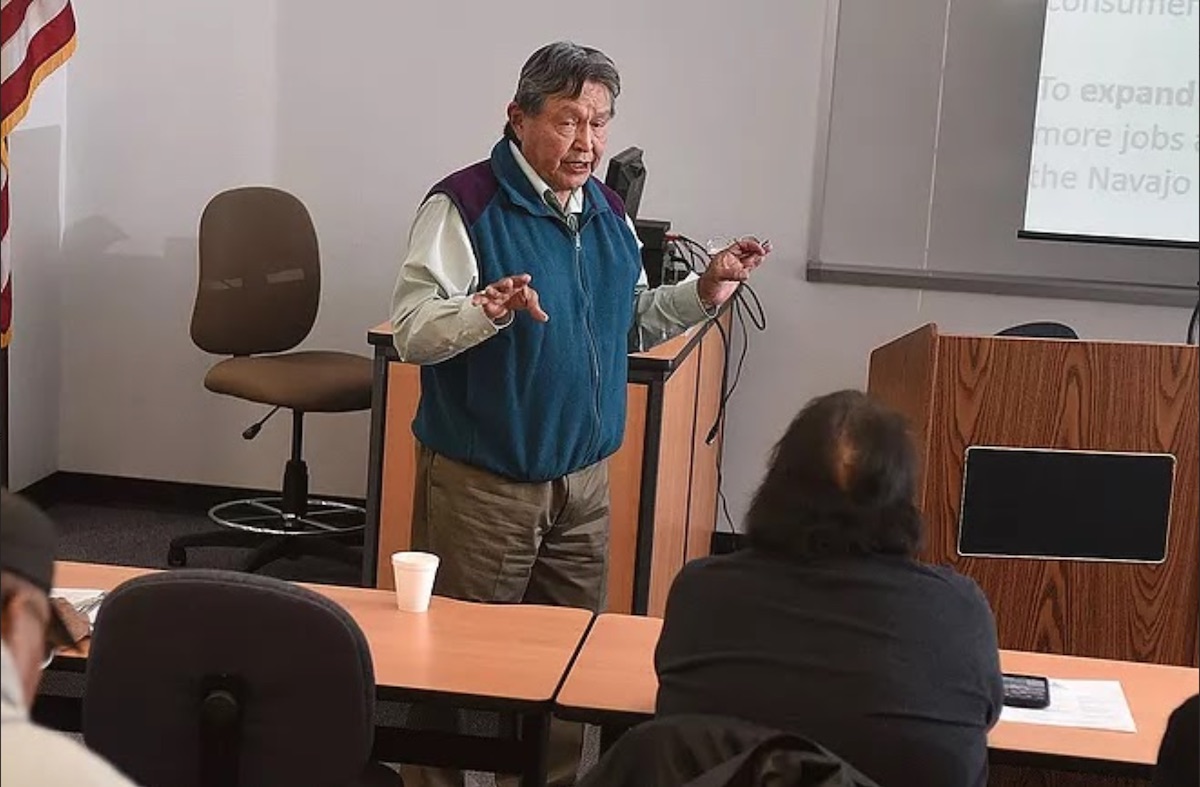

Jeff Begay, chair of the Dineh Chamber of CommerceGiven the estimates for economic leakage, Chamber Chair Jeff Begay thinks better enforcement of the act is one step toward helping improve the Nation’s economy and create a better business environment. He says much of the money entering the Navajo reservation will just as quickly leave it without administration intervention.

Jeff Begay, chair of the Dineh Chamber of CommerceGiven the estimates for economic leakage, Chamber Chair Jeff Begay thinks better enforcement of the act is one step toward helping improve the Nation’s economy and create a better business environment. He says much of the money entering the Navajo reservation will just as quickly leave it without administration intervention.

“We have $1.8 billion awarded to the tribe (under the American Rescue Plan), and we suspect that 90 percent of that or more will go to off-reservation businesses,” Begay told Tribal Business News. “We are going to create millionaires in these border town companies, whereas our Navajo businesses should be the millionaires.”

Want more news like this? Get the free weekly newsletter.

The Chamber’s proposal is for tribal operations to take a closer look at picking companies from the “Navajo source list,” a list of certified Navajo-owned companies seeking preferential treatment for Navajo contracts. The list functions similar to the federal government’s 8(a) program by giving Navajo-owned companies an advantage in bidding on Navajo Nation contracts, according to Chamber Secretary Al Henderson.

“We want to stand up more Navajo businesses. We can’t have another uncertainty where we’re just completely locked out of opportunities and have to start all over again,” Henderson said. “Seventy percent is a high number. We need to improve that number.”

At the same time, Begay said the process for becoming certified is guided by the government and ponderously slow, which discourages companies from seeking the certification in the first place.

That slow pace can even extend to paying Navajo contractors who have secured work. To that end, Begay cited an example of the tribal government allegedly taking more than three years to pay companies for the work performed under a Navajo contract.

“These are impediments to cash flow and they can stop people from being able to operate,” Henderson said. “They have subcontractors that they have to pay, and because of the lengthy payments of invoices, especially alongside some of the startup costs, they’re immediately discouraged. Then they leave, they disappear, they’re no longer part of the preference.”

Begay said the solution is twofold: Build a more transparent system of payment and approval, and allow businesses to get ready for certification on their own, rather than involving the government from step one.

“A self-certification process might be the answer, much like the federal government does. You put on forms that you are a bona fide Navajo Indian, you have a license and you meet all the necessary requirements,” Begay said. “Other things would be to minimize the bureaucracy on the tribal government side.”

With technical assistance and support, Navajo entrepreneurs could get businesses off the ground faster through private partnerships than through government programs, Henderson added. The Chamber has even floated the concept of creating its own incubator.

“The onus should be to teach ourselves to become capable of performing the work,” Henderson said.

Asked and answered

The Chamber discussed these concerns with the Navajo Nation bureaucracy during a roundtable discussion with roughly 100 Navajo-owned businesses and Vice President Myron Lizer in early September.

Begay called the meeting “productive,” and said Lizer listened intently to the businesses who participated.

“He did hear their complaints and their issues, so we’re really appreciative of that fact, and we applaud him for coming out to the frontline and facing the gunfire so we can begin the process of documenting and recommending changes,” Begay said.

Henderson echoed the sentiment, but noted that Lizer didn’t offer a commitment to the Chamber’s primary goal, which was for the Nation to earmark $5 million of its $1.8 billion ARPA funds specifically for small business development.

The Navajo Nation Office of the Vice President did not respond to multiple requests for comment before this report was published.

“I think often about getting the Nation to support the small business community with this ARPA money,” Henderson said. Supporting the business climate with small business development funds “could catapult the Chamber into an era where we teach and learn and build the Nation’s small businesses up.”

That kind of money could spell huge increases in Chamber activity, and by extension, an uptick in the reservation’s business climate through increased technical training, funding and support, Henderson said.

“We’re at the cusp of changing history, and the entirety of the Navajo Nation economy,” he added.

This land is our land

Another issue Navajo entrepreneurs perpetually face is finding a physical space to work. The “cumbersome” process of leasing land and the 25-year lease system conspire to drive prospective business owners into nearby cities rather than staying on the reservation, he said.

Prior Tribal Business News reporting bears that out. Heather Fleming, executive director of Tuba City, Ariz.-based business incubator Change Labs, highlighted the challenges she faced in the nonprofit’s search for a new headquarters building.

“People are at a disadvantage in so many different ways, and the crux of it is the land,” Fleming said in the June 14 report. “It’s key in solving a lot of the shared challenges that Native entrepreneurs have.”

Begay also cited his experience in launching a construction business. A process that would have taken two to three years on the reservation took him less than a month off the reservation.

“It was a matter of less than a month to be in business once I had the license and the funding,” Begay said. “Less than a month versus two years, three years, maybe even longer to get permission through the bureaucracy to finally get approval. That’s how bad it is.”

Henderson singled out the trust land arrangement between the federal government and tribal governments as a key pain point for business development.

Under the current arrangement, land development has to be approved by both tribal and federal government agencies before it can be used. On its own, that process can take between two and three years, assuming approval is granted. However, many organizations — including Change Labs — discover that receiving land use approvals is far from guaranteed.

If land is approved for business use, it’s offered to the business owner on a 25-year lease, which often disincentivizes entrepreneurs from making any capital improvements to buildings or land because they won’t be using it forever, Henderson said.

“If you go through Navajo Nation, you see a lot of former retail establishments that are vacant and deteriorating. Some of us call it an eyesore,” Henderson said. “Why would a sound person want to go ahead and improve the property they don’t get a return on? They should feel like they have at least a value that the Nation would give them, as it would be in the more private real estate market.”

“If I own a house or a private business, at least there is a buyer. That buyer may be able to give us a negotiated price to assume ownership.”

In Henderson’s view, a program should be created to pay leaseholders for the value of their improvements to existing buildings at the end of a lease.

Begay took it a step further. He proposed that the Navajo government pre-approve land for business development and leasing so that the process moves faster.

In that regards, the Dineh Chamber could even step in as a realty agent. As a group of small business owners, the Chamber could take on the responsibility of improving existing properties and facilitate tenancy, Henderson said.

“I think we can do a better job than the government with this,” he said.

All of those measures could currently be a long way off, Henderson acknowledged. Finding solutions for small business owners has been a challenge since long before the pandemic erupted.

“At no time in the last 50 years has any effort toward that kind of a resolution been entertained by the lawmaking body, nor has a presidential candidate,” Henderson said. “All they say is that this is trust territory and that’s under the auspices of the federal government with the BIA as a trustee. And that’s where the issue stops.”

‘We want to rely on ourselves’

Between the land leasing process, tight regulations and non-Navajo contract awards, many businesses simply build off of the reservation, which drains talent from the communities that need it the most, Begay said.

Begay pointed to data collected during applications for pandemic assistance through the Navajo Nation’s CARES Act funding as one example. Of the more than 6,000 applications, “between 200 and 300” businesses actually operated from Navajo land.

Those issues are compounded when Navajo Nation awards contracts “primarily” to non-Navajo companies, Begay added.

This broad combination of factors all work to hamper the Chamber’s ultimate goal, which is to improve the reservation’s private sector economy.

“The rest of America operates primarily on a private, entrepreneurial system which pays taxes and supports tribal government, state government, and county government,” Begay said. “We don’t do that on Navajo. We depend on federal funding for just about everything.

“We are trying to establish a Navajo private sector so that we can have a private sector economy rather than a subsidized economy from the tribal and federal government.”

Untangling the complex process of starting a business on Navajo land — from leasing a building to applying for preferential treatment in Navajo contracting — needs to be a top priority for tribal leaders hoping to improve economic development, Begay said.

“We need to get our leadership on the legislative side and the executive side to understand that,” he said. “We have a very slow process out here and things need to change, and our leadership needs to understand that.”