- Details

- By Chez Oxendine

- Food | Agriculture

Farmers in need have received $800 million through the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s new debt relief program made possible by the Inflation Reduction Act.

The funds come from a $3.1 billion allocation intended to relieve distressed borrowers of some or all of their debt. The assistance targets both direct borrowers and borrowers using private loans guaranteed by the USDA.

The debt relief is part of an agency-wide effort to improve the USDA’s lending programs and get producers back to farming.

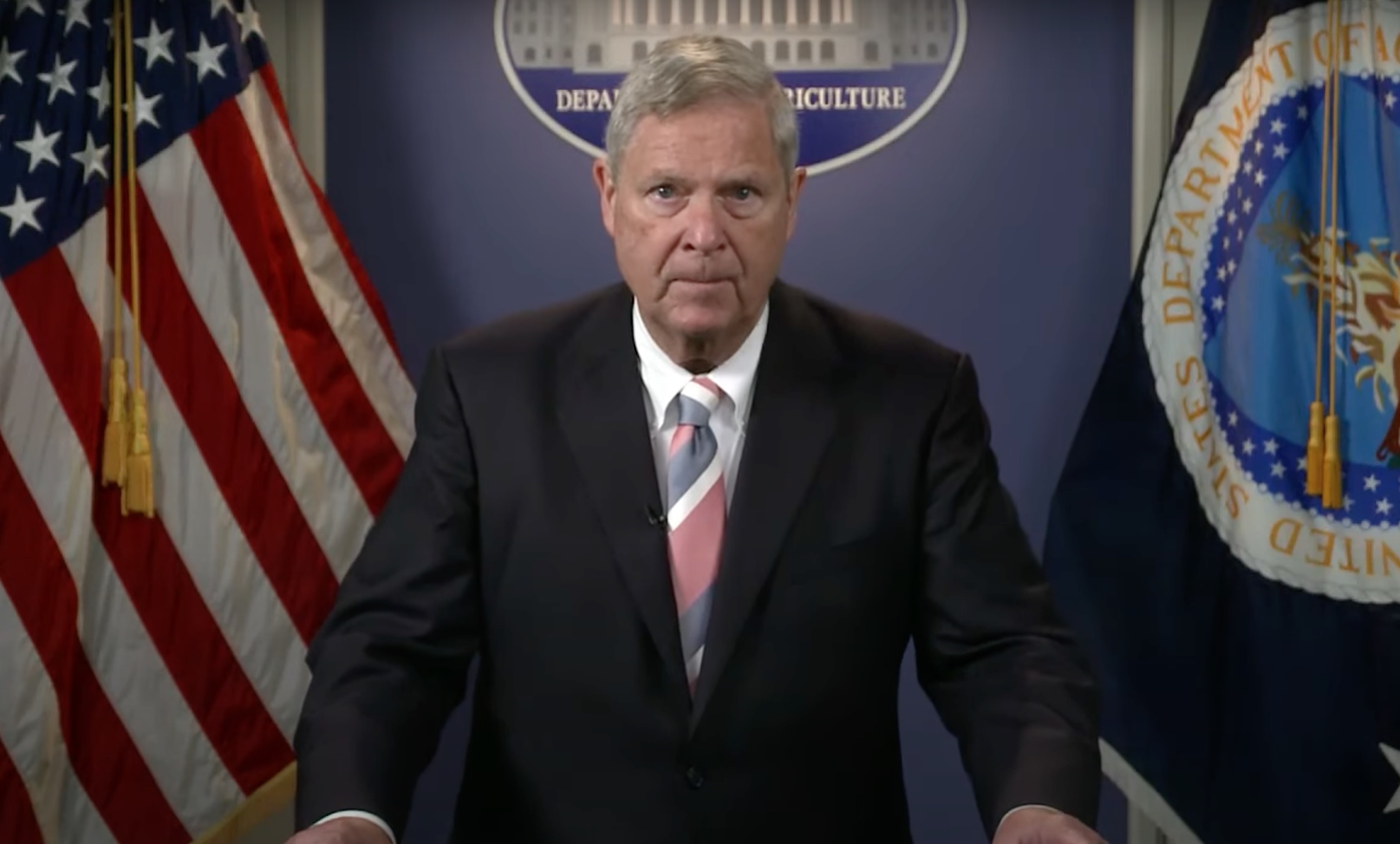

“Through no fault of their own, our nation’s farmers and ranchers have faced incredibly tough circumstances over the last few years,” Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack said in a statement. “The funding included in today’s announcement helps keep our farmers farming and provides a fresh start for producers in challenging positions.”

Through this initial distribution of $800 million, the USDA has brought 11,000 delinquent accounts current and paid those same producers’ next annual installments. Vilsack said that the money has also resolved the debt of 2,100 borrowers who lost their farms to foreclosure, enabling these farmers to get a fresh start.

The USDA will use another $500 million to assist borrowers who used the Farm Service Agency’s (FSA) disaster set-aside option to delay loan payments, borrowers with more complex cases, and borrowers who are still waiting on relief.

Vilsack called the initial disbursement the “first phase” of the USDA’s debt relief program, meant to “stop the bleeding” among the most distressed farmers.

“These are just the first steps,” Vilsack said. “There’s more to come.”

Most agricultural organizations praised the agency’s swift dispersal of these initial funds.

John Zippert, chairperson of the Rural Coalition, an alliance of farmers, farm workers, Indigenous, migrant, and working people, said the USDA’s maneuver quickly got money into farmers’ hands.

“We commend USDA for moving expeditiously and with resolve to speed critical relief in the form of debt payments for at-risk producers and underserved farmers and ranchers facing financial distress,” Zippert said in a statement. “We are hopeful that the economically distressed underserved producers we serve will now receive the prompt and long-awaited support they need to stabilize their operations in the face of the pandemic and growing increases in cost of inputs and land.”

Toni Stanger-McLaughlin, CEO of the Native American Agriculture Fund (NAAF), wrote in an open letter that the measure would prevent a wave of foreclosures amid rising inflation and natural disasters.

“Without this assistance, many borrowers could have faced accelerated loans resulting in foreclosure,” Stanger-McLaughlin wrote. “For other borrowers, it was just bad timing; with inflation, the cost of production, and implements compounded by other issues such as natural disasters, borrowers found themselves barely making it and potentially unable to make next year’s payment. Like the Federal Government did in the 1980 Farm Credit Crisis, some producers were provided a lifeline.”

These debt relief efforts could stop further generational erosion of Native-owned farms and properties lost to foreclosures. According to Stanger-McLaugh, the program represents a way for the USDA and FSA to use the “tools in their toolbox,” granting new authority to assist borrowers in previously unseen ways.

“While working in the Civil Rights Office at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, I witnessed first-hand the devastation of hard-working families that, at one point or another, were faced with extenuating circumstances that required a simple hand-up. When USDA wasn’t able to provide that, in some circumstances, it meant a loss of everything,” Stanger-McLaughlin wrote. “The authority to administer these programs without funding left many of these services useless until now.”

The new debt relief follows a previous $4 billion allocation under the American Rescue Plan Act to pay up to 120 percent of outstanding FSA direct loans for marginalized producers. After white farmer sued for reverse discrimination and the relief became mired in a court battle, lawmakers repealed the funding in the Inflation Reduction Act and replaced it with the new fund that targets distressed borrowers.

While this wider scope of the latest debt relief program aims to sidestep the legal concerns that plagued the APRA allocation and has garnered praise from some Native-led organizations, others note that the broader scope — which doesn’t differentiate between “socially advantaged” and “socially disadvantaged” producers — and lower allocation means fewer marginalized farmers will receive aid.

The Inflation Reduction Act also includes $2.2 billion for farmers who have suffered “discrimination” under the USDA’s lending programs. The agency has opened up public comment on how to implement the fund, the Federal Register entry for which can be found here.

The agency seeks input specifically on how to identify eligible farmers, what documentation should be used to verify the discrimination against them, and what should be factored into eventual payouts.

Vilsack said the discrimination relief broadened the USDA’s available tools for helping right the wrongs of past discriminatory behavior on the the agecy’s behalf and “supporting those who are willing to dedicate their lives to our nation’s food security and rural communities.”

“This is a continued step in the right direction,” Stanger-McLaughlin wrote in a statement.

Some public comments submitted to the Federal Register contend that farmers already promised money under the ARPA provision should be first in line for funds under new discrimination fund.

“I think that farmers, especially socially disadvantaged farmers who were promised 120% debt relief back in March of 2021, who counted on the signed agreement with USDA to provide debt relief and still have not received it, should be at the top of the list of farmers who have been discriminated against,” wrote Cindy Polk from Lenapah, Okla. “I realize there were legal battles in court over the ARPA socially disadvantaged relief, but those farmers have been through economic, severe emotional and mental distress daily since the broken promise of USDA.”

The USDA will host three virtual listening sessions the discrimination relef in addition to its 30-day comment period. Information on those listening sessions can be found here.