- Details

- By Mitch Galloway

- Food | Agriculture

Gone are the silver cans of pork and beef, the gelatin insides almost mocking Gary Besaw.

Nowadays, his shelves are stocked with fresh meat from Indigenous producers.

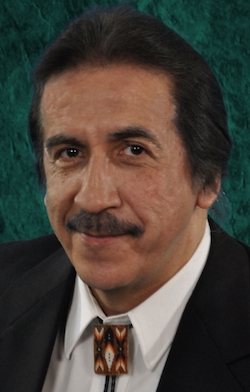

Gary Besaw“Food is medicine,” said Besaw, a member of the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin and its director of agriculture.

Gary Besaw“Food is medicine,” said Besaw, a member of the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin and its director of agriculture.

“When we look at the predominance of diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, obesity, and all of those health indicators, we know we need to get away from processed foods and go back to the way we should be, and that's having healthy fresh foods and growing regular food.”

To do that, Besaw and other Tribes needed support in the 2018 Farm Bill. What they received included 63 provisions catering to Indian Country needs, echoing their ancestors’ voices and rebuilding tribal and inner-tribal communities and economies.

Once the Farm Bill became law, the USDA authorized the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR), allowing tribal organizations to make their own food-purchasing decisions and include locally grown foods. Five years later, the FDPIR pilot program — also known as the 638 Self-Determination Demonstration Project or “the 638 FDPIR”— is opening more than just producers’ doors, according to Besaw.

“The project allowed us to take a look at all of the food products on the shelves in our Food Distribution Program and replace existing products on the shelves with products that we want,” he said.

“Instead of the (Agricultural Marketing Service) purchasing them, we would purchase them. We look at the Angus beef from Oneida Nation Farm, and they have a beautiful marble … I mean, oh, my God. It makes a world of difference.”

That difference is what Besaw and others aim to build off in the 2023 Farm Bill.

FIRST THINGS FIRST: INCLUSION

“And Tribes.”

Those two words now included in 2018 Farm Bill provisions shows how far Indian County’s come in the national food discussion, said Carly Hotvedt, a citizen of Cherokee Nation and associate director of the Indigenous Food and Ag Initiative. Previously, she said Native farmers and ranchers were mostly neglected and left out of farm bill discussions.

Nowadays, Tribes have direct access to farm-bill conservation.

“Every single roundtable we were at there was some sort of conservation priority topic, whether that was direct funding for tribal conservation districts, whether it was self-governance authority through Natural Resource Conservation work, (or) whether that was addressing some of the leasing challenges – like (Bureau of Indian Affair) leases and their length of tenure lining up with the timeframe for NRCS contracts or FSA contracts,” Hotvedt said.

Carly Hotvedt presents on behalf of the Native Farm Bill Coalition at Fond du Lac Tribal College in Wisconsin. (Courtesy photo)

Carly Hotvedt presents on behalf of the Native Farm Bill Coalition at Fond du Lac Tribal College in Wisconsin. (Courtesy photo)

Current provisions in the 2018 Farm Bill make it easier to navigate current programs and create more opportunities for local investments, she said.

“There's been a real resurgence in investment in how food systems work,” added Hotvedt, noting Tribes want to take control of where their food comes from and who produces it.

“When COVID hit, we saw the deficits of availability on store shelves and a lack of those products that were needed.”

The 638 model, for example, allows participating Tribes to purchase ground beef and bison from Oneida Nation. Historically, the USDA provides all food in the FDPIR program. The 638 Oneida/Menominee pilot project, however, allows Tribes to pick what foods they’d like to procure to supplant existing products on the shelves.

Eight tribes from across Indian Country made up the initial pilot testing period, but additional funding will allow that number to grow. A second round of funding awards is expected this summer.

The pilot programs are important for the growth of Indigenous communities, according to Vanessa Miller, Oneida Nation’s Food and Agriculture area manager who works with Besaw and the Menominee Indian Tribe.

She wants to make them permanent.

“In the next farm bill, we want to increase the program’s flexibility through self-governance and allow us to respond to the unpredictability of growing seasons and current economic conditions,” Miller said. “Demand is increasing. We cannot keep up, specifically with our beef from the demand of this program.”

Miller said she sometimes needs to order 75% more than the original committed quantity.

“We definitely believe from anecdotal evidence that people place higher value on the quality, A, and B, people see value and pride and a need to connect to our culture and our communities via our food pathways,” Miller said.

STATUS OF 2023 FARM BILL

While most tribal leaders, farmers and advocates acknowledge that the 2018 Farm Bill, with its 60-plus tribal provisions, was a landmark victory for tribes, there were still many key Indian Country priorities that were left out of the legislation, according to the authors of a policy brief published in September 2020. Those key policy priorities ”remain vitally important to the ability of tribal nations and individual Native food producers to advance their food sovereignty, production, and security initiatives,” the report notes.

Some of those priorities are as simple as policy fixes to remove roadblocks that tribes and producers face from federal programs and federal agencies, according to participants in a March roundtable discussion hosted by the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs. That includes streamlining procedures for working with government agencies such as the Bureau of Indian Affairs and defining what “Indian land” actually means in the Farm Bill, roundtable participant Ryan Lankford, chairman of the Montana State FSA Committee and Island Mountain Development Group, said.

During the roundtable, which featured tribal agriculture leaders from Alaska, the lower 48 and Hawaii, numerous participants revealed a clear priority as to what Indian Country needs in the 2023 Farm Bill: self-determination.

Self-determination was also one of the top priorities discussed by Cherokee Nation Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. at a February “regional fly-in” meeting with Congressional leaders about the 2023 Farm Bill. During the meeting, which was arranged by The Native Farm Bill Coalition, Hoskin discussed several priorities including self-determination, expanding USDA funding for meat process programs, allowing tribes to administer the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program — also known as SNAP — and getting the USDA to allow traditional Indigenous foods in FDPIR.

As with the 2018 Farm Bill, tribal leaders and Native agriculture advocates are working closely together to coalesce around issues and advance Native priorities in the 2023 legislation. The Native Farm Bill Coalition represents 208 tribes and 62-related organizations. According to USDA data, more than 79,000 farmers and ranchers identify as American Indian or Alaska Natives — about 2% of all producers.

Farm sales in 2017 accounted for $3.5 billion for Native producers. That number will grow as long as opportunities exist, said Toni Stanger-McLaughlin, CEO of the Native American Agricultural Fund, a charitable trust serving Native American producers and ranchers.

Stanger-McLaughlin said there’s a public misunderstanding in how Indian Country operates. She referenced a time her daughter’s schoolmates asked if Native Americans still lived in teepees.

“How can we amplify each other's voices while also getting rid of some fear around Tribes in the unknown?” Stanger-McLaughlin asked. “The unintentional ignorance about how our tribal governments operate and the type of agriculture we engage in exist. People believe we're not in this modern age — that we're not adapting. Well, we're embracing our traditions and our cultures while also taking in this new technology and adapting to different practices.”

Stanger-McLaughlin called the 2018 Farm Bill monumental, noting it created a unified voice for Indian County. Some of its provisions supporting Native agriculture include USDA programs related to production, rural infrastructure, economic development, conservation, forestry, and nutrition assistance. (See the complete list here.)

“The (638) pilot program was put forth to show that Tribes and their governing bodies have the ability to administer programs that often go to states,” Stanger-McLaughlin said.

“No one's going to be able to take care of a community like those who live in it. It’s also strengthening the dollar within that community … There are a lot of positives to regionalizing, and right now, the structure to do that in rural America is through tribal governments.”

Current farm bill programming ends in September. Stanger-McLaughlin said high inflation and the debt ceiling are some of the barriers affecting its passage.

“I hope that we get a farm bill,” she said. “If we don't, then I hope that the programs that exist that are vital to Indian Country … still find some funding.”

To avoid that scenario, Hotvedt encourages tribal farmers and ranchers to contact their local legislators. Farm bill listening sessions are also taking place, said Hotvedt, where locals can learn about Tribes’ stances on various provisions and issues.

Issues like supplying tribal food to tribal nations.

“Food is medicine,” Besaw said again.

“With the next Farm Bill, we are demanding greater control of the types of healthy foods we can purchase when supplanting existing USDA foods available for our clients. Things like maple syrup, for example. It’s going to be a great opportunity for us.”

Mitch Galloway is the associate editor of the Michigan Farm News, the publication of the Michigan Farm Bureau. He covers all-things agriculture. Previously, he covered agriculture and manufacturing for regional business publication MiBiz.