- Details

- By Thomas Stratmann

- Opinion | Op-Ed

Guest Essay. Last month, the Treasury Department finalized two regulations that tribal leaders have sought for decades—one confirming that tribal general welfare benefits aren’t taxable income for recipients, and the other clarifying that wholly owned tribal business entities share their tribe’s tax-exempt status.

[This story first appeared on Rules & Results and is republished with permission.]

The tribal leaders quoted in the Treasury announcement are right to celebrate. These rules matter. But the story they tell isn’t primarily one of progress. It’s a case study in how regulatory uncertainty quietly strangles economic development—and how the federal system that governs Indian Country makes that uncertainty almost inevitable.

The Real Story Is the Timeline

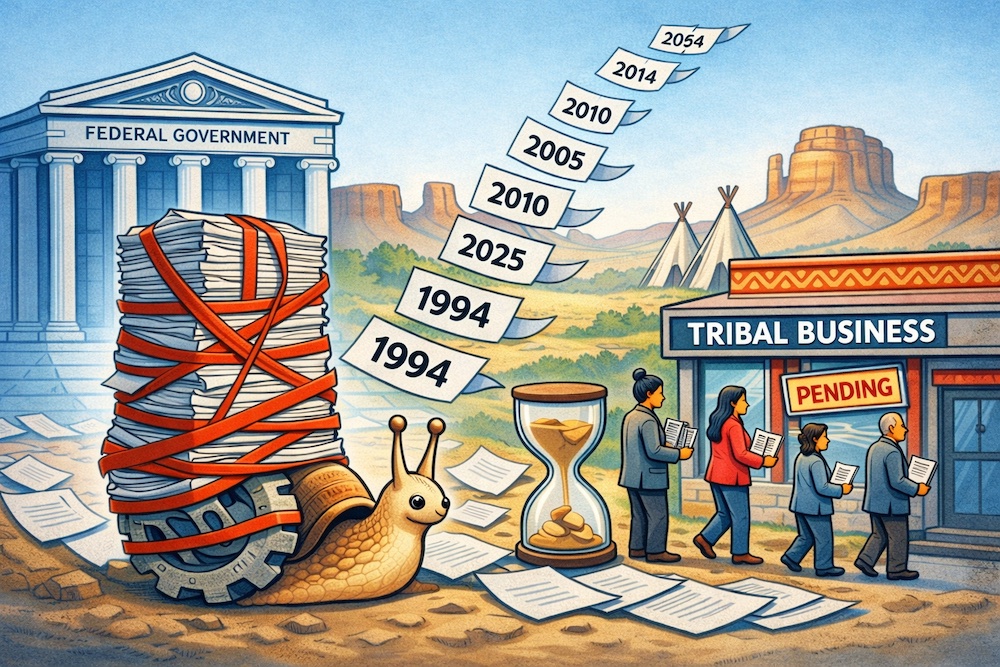

Consider what we’re actually celebrating: the IRS has finally, after roughly 30 years of tribal advocacy—dating back to the early 1990s—confirmed in writing what the underlying legal principles arguably required all along. (See “Key Milestones” below for the whole timeline.)

During those three decades, tribes structured deals defensively, paid higher borrowing costs, delayed projects, and sometimes paid federal taxes they may not have owed—all because Washington couldn’t produce clear guidance. As the Treasury Department acknowledged, the uncertainty “created a significant barrier to economic development,” “impact[ed] access to capital,” and forced tribes to guess “the cost of financing” rather than focus on growth.

Congress passed the Tribal General Welfare Exclusion Act in 2014. It took eleven years to finalize the implementing regulation.

This isn’t a story about government working. It’s a story about how government-created ambiguity imposes real costs on real communities, year after year, while the bureaucratic process grinds forward at its own pace. Research consistently shows that institutional complexity—overlapping jurisdictions, unclear rules, unpredictable enforcement—depresses investment and economic activity. (For more on how institutional quality correlates with reservation incomes, see my earlier post on the Reservation Economic Freedom Index, based on my paper in Public Choice.) A 30-year wait for tax clarity is a 30-year period during which capital that could have flowed into reservation economies went elsewhere or never materialized.

Regulatory Clarity Is Good—But It’s Still Regulation

Treasury Secretary Bessent framed the announcement as part of “the administration’s pro-growth and deregulatory agenda.” The characterization deserves scrutiny.

What happened last week is that the federal government finally wrote down rules clarifying how it will apply its taxing power. That’s welcome. It reduces uncertainty. But the underlying framework remains: tribes needed federal permission—or at a minimum, federal confirmation—to know how their own welfare programs and business entities would be treated.

Under the final regulations, tribes have “sole discretion” to determine whether a benefit promotes general welfare, and the IRS will defer to that determination. Benefits can be provided regardless of financial need and may be distributed uniformly to all eligible tribal members. This is coherent: tribes are governments, and the regulations appropriately recognize their authority to define welfare under their own laws and customs. States don’t need IRS permission to confirm that their welfare programs aren’t taxable to recipients—that’s inherent in state sovereignty. Tribes shouldn’t need it either.

But consider what this deference required: a decade of advocacy after Congress acted, extensive tribal consultation, 41 public comments, and a 28-page Federal Register notice. Tribes now have clearer rules to follow. They don’t have fewer rules. The compliance apparatus remains; it’s just better documented.

Competitive Questions Worth Considering

The regulations raise an implication worth thinking through: tribal enterprises that are wholly owned and chartered under tribal law are now clearly exempt from federal income tax. They compete in markets alongside businesses that pay that tax.

This isn’t an argument against tribal sovereignty. Tribes are governments, and governments generally don’t pay income tax to other governments. But the economic logic of government-owned enterprises competing in private markets is worth examining regardless of the government in question.

When governments run businesses—whether states, municipalities, or tribes—they often enjoy advantages that private competitors don’t: tax exemptions, implicit subsidies, and access to sovereign borrowing. Economists call this state capitalism, and the competitive distortions it can create are well-documented. The question for reservation economies is whether tribal prosperity is best served by tribes acting as business operators or by tribes creating the institutional conditions—clear property rights, predictable courts, limited regulation—that allow private enterprise, including tribally owned private enterprise, to flourish.

What Would Real Progress Look Like?

The celebration around these regulations is understandable. After 30 years, you take the wins you can get. But it’s worth asking what a genuinely pro-development, pro-sovereignty framework would look like.

It probably wouldn’t require tribes to wait three decades for the IRS to confirm their legal status. It wouldn’t treat federal “guidance” as a prerequisite for tribal self-governance. And it would address the deeper structural barriers that research has identified as impediments to reservation prosperity: fractionated land ownership that makes economic use of land nearly impossible; trust status that prevents land from being used as collateral; checkerboard jurisdiction that raises transaction costs for any development project; and regulatory complexity that deters outside investment and constrains tribal decision-making. (On fractionation specifically, see Russ and Stratmann 2016; on property rights and development more broadly, see the work of Cornell and Kalt at the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development.)

The Treasury announcement is a modest improvement within a system that remains resistant to economic dynamism in Indian Country. Tribal leaders know this, which is why the same announcement included requests for further guidance on partially-owned enterprises that could undermine implementation of the very rules just finalized.

The bureaucracy giveth, and the bureaucracy taketh away.

Tribal communities deserve better than a system where “progress” means federal agencies finally doing what Congress told them to do a decade ago. They deserve a framework that respects genuine sovereignty—not sovereignty-as-administered-by-Washington, but the real thing: the freedom to govern, build, and prosper without perpetual dependence on federal permission slips.

These new rules are better than the ones that came before. That’s a low bar, and everyone involved knows it.

Key Milestones: 30 Years to Tax Clarity

Early 1990s — Tribal governments begin requesting written guidance from Treasury and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) on the tax treatment of general welfare benefits and tribally-owned business entities. Without clear rules, tribes face audit risk and structure programs defensively.

June 3, 2014 — The IRS issues Revenue Procedure 2014-35, creating interim “safe harbors” that allow certain tribal general welfare benefits to be excluded from taxable income. This reduces immediate audit uncertainty but is not a permanent solution.

September 26, 2014 — Congress passes the Tribal General Welfare Exclusion Act, adding Section 139E to the Internal Revenue Code. The law codifies that qualifying tribal general welfare benefits are not taxable and directs the IRS to defer to tribal program determinations. It also mandates creation of a Treasury Tribal Advisory Committee (TTAC).

February 10, 2015 — The TTAC is formally established to advise Treasury on tribal tax matters and help develop regulations implementing the 2014 Act.

April 16, 2015 — The IRS issues Notice 2015-34, clarifying that taxpayers may continue relying on the 2014 safe harbors while permanent regulations are developed.

June 20, 2019 — The TTAC holds its first public meeting—more than four years after its formal establishment. The committee begins substantive work on regulatory recommendations.

September 17, 2024 — Treasury publishes a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on Section 139E, translating the 2014 statute into binding regulations. Public and tribal comment periods follow.

October 9, 2024 — Treasury publishes a separate proposed rule on the federal income tax classification of entities wholly owned by tribal governments—addressing the 30-year-old question of whether tribally-chartered corporations share their tribe’s tax-exempt status.

November–December 2024 — Treasury conducts formal government-to-government consultations with tribal leaders on both proposed rules.

December 16, 2025 — Final regulations on both tribal general welfare benefits and tribally-owned entities are published in the Federal Register, concluding a regulatory process that spanned three decades.

Thomas Stratmann is a University Professor of Economics and Law at George Mason University and a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center. He publishes Rules & Results on Substack and created the Reservation Economic Freedom Index.