- Details

- By Lynn Liu, Medill News Service

- Policy and Law

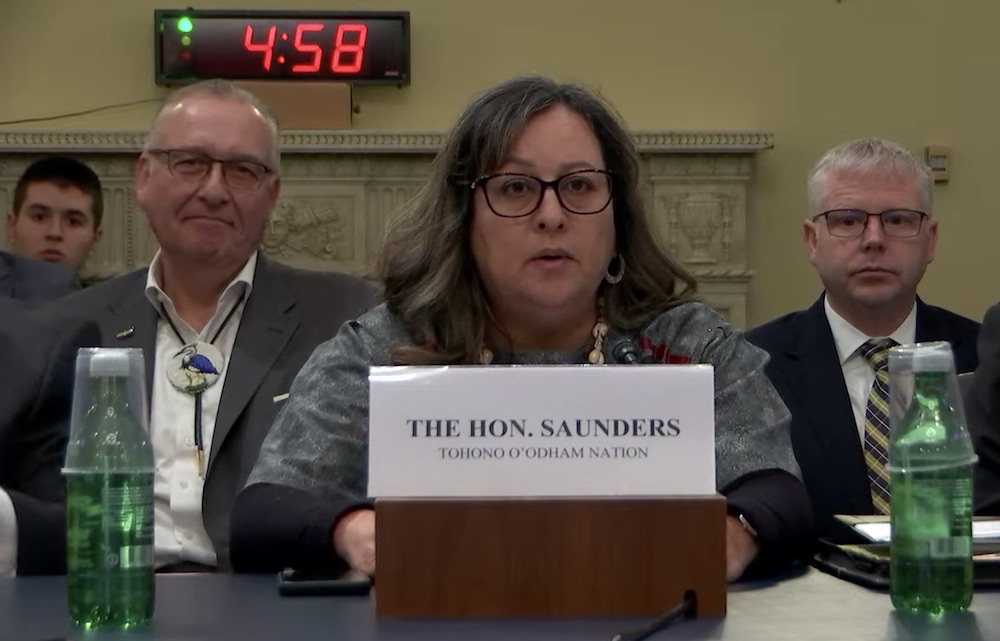

WASHINGTON—Sinkholes, potholes and washed-out bridges were top of mind for the Tohono O’odham Nation’s vice chair when she spoke to a congressional subcommittee last week.

“Those roads are dangerous for our members as well as our visitors,” Wavalene Saunders, vice chairwoman of Tohono O'odham Nation, said on Wednesday. “During monsoon season, flooding completely washes out our roads and makes them impassable.”

Saunders was one of the leaders from four tribes to speak with members of Congress about the need for the federal government to increase funding and cut out bureaucratic hurdles that make it difficult for tribes to thrive. She was joined at a House subcommittee meeting on “Unlocking Indian Country’s Economic Potential” by leaders of the Confederated Tribes of Chehalis Reservation, Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation and the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians.

Members of Congress who organized the hearing are looking for ways to give tribal governments more control over their land.

Saunders blamed the federal government for making it difficult for tribes to solve their own problems.

“We've been trying to address our road issues at the tribal level,” Saunders said after the hearing. “Before anything else, that's the top priority for us to get addressed: Transportation.”

Situated along the Mexican border in the desert near Tucson, Ariz., Tohono O'odham Nation is one of the largest Indian nations in the U.S. in terms of land holdings, with 2.8 million acres. It can take tribal members up to 50 minutes to drive to the nearest city, creating economic challenges when it comes to accessing medical care and buying groceries.

Creating solutions to those challenges is often made more difficult because of the many land-use restrictions imposed on Indian lands.

Typically, Indian lands fall into one of three categories specified in the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act (IRA): Trust land is held in trust for the benefit of Indian tribes or individuals and is managed by the United States through the Department of the Interior; fee land is owned by the Indian tribes or an individual Indian; restricted fee land is fee land under restrictions like taxation.

“In my view, the idea of trust land is not normal and should be fixed to recognize that our nation is the owner of our lands within our treaty defined reservations,” Joseph Rupnick, chairman of Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, said during the hearing.

It’s taken 14 years for Potawatomi Nation to get permission to build a retail shopping plaza with a convenience store — and the project has yet to be built, according to Rupnick. Before the project could start, the tribal government had to apply to the Interior Department’s Bureau of Indian Affairs to turn the trust status of the construction land into fee status.

Rep. Jenniffer González-Colón (R-P.R.) said she was surprised at the restrictions Indian nations face when they try to use their own land.

“I believe that land is the most important resource you have for economic development… and when you’ve got all those restrictions, there's no way you can succeed,” she said.

Some members of Congress vowed to work on the problem, including Rep. Harriet Hageman (R-Wyo.) chair of the Subcommittee on Indian and Insular Affairs, which held the hearing.

“Yesterday, I introduced a bill that would allow all federally recognized tribes to authorize leases of up to 99 years,” Hageman said. “Congress should continue to provide additional tools to all federally recognized Indian tribes to conduct the activities that they choose. We should ensure that Indian lands… are able to be used as the tribes want to use them.”