- Details

- By Brian Edwards

- Sovereignty

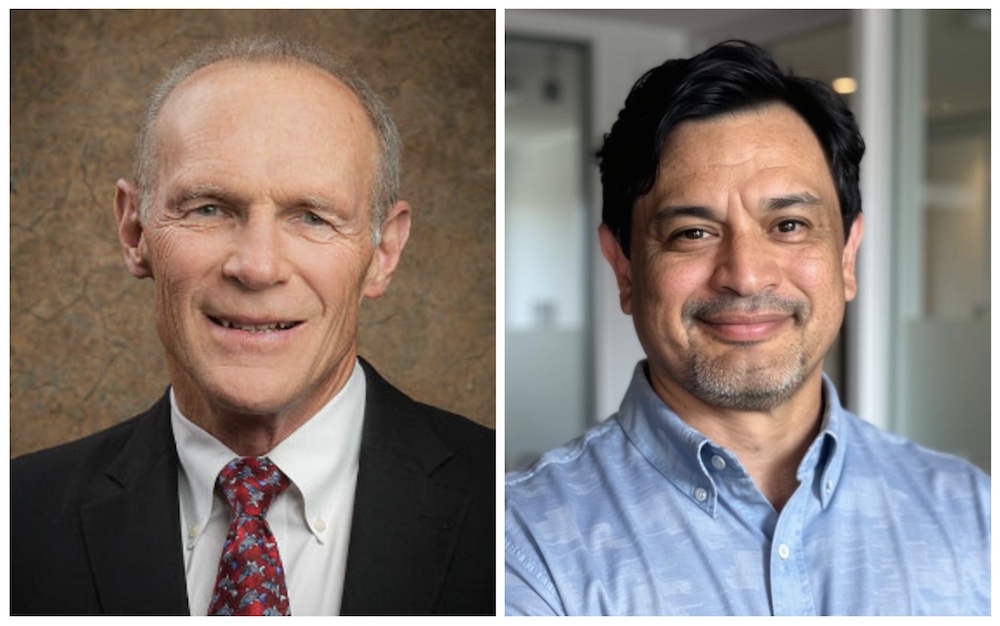

After nearly four decades building the Harvard Project on Indigenous Governance and Development into the preeminent research center on tribal governance, Joseph P. Kalt handed the reins to economist Randall Akee this summer, marking a generational transition in how academic institutions study and support Native nation-building.

Kalt co-founded what was first known as the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development in 1987 alongside sociologist Stephen Cornell during an era when tribes were just beginning to reclaim self-determination following the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act. Their first graduate student research assistant was Manley A. Begay, Jr., a Navajo doctoral student who would later become co-director of the project in 1997. What started as three academics driving rental cars across Indian Country became a nearly 40-year effort documenting a fundamental insight: sovereignty matters, but only when backed by effective governance.

Akee, a Native Hawaiian economist who earned his PhD from Harvard's Kennedy School in 2006 and served as a senior economist in the Biden White House Council of Economic Advisers, now returns to Cambridge as the Harvard Project's faculty director and the Julie Johnson Kidd Professor of Indigenous Governance and Development. He founded the Association for Economics Researchers in Indigenous Peoples (AERIP) and has become what Kalt calls “the leading scholar doing work on not only economic conditions, but social conditions, education, health, governance in indigenous communities.”

Next week, Kalt will receive recognition for his work at the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) 82nd annual convention in Seattle on Nov. 19-20. The event will also feature the Honoring Nations program — which recognizes excellence in tribal governance — announcing its 2025 award winners.

In a late-August conversation, the two scholars spoke with Tribal Business News about the Harvard Project's core findings on tribal sovereignty and governance, the challenges policymakers still face in understanding Indian Country and where they see Native governance heading over the next 25 years.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Joe, when you co-founded the Harvard Project in 1987, tribes were just beginning to reclaim self-determination. What surprised you most about what was happening in those early trips?

JOE KALT: We tried to first consciously focus on tribes that were in the news for doing really cool things. This is the mid-1980s, so Mississippi Choctaw, for example, had become quite well known for their various industrial efforts, the White Mountain Apache for their wildlife management, things like that. There was a lot of poverty out there, and we consciously tried to take a look at the places that seemed to be breaking those patterns of poverty, as well as the places that were still struggling so much.

I'm an economist by training, and so we were focused on economic development. For folks like Randy and I, we get trained that it's all about resources and human capital — your educational attainment and maybe your access to capital. That's where economic development is going to come from.

But when we got out there and really started to talk and try to listen, we spent the first three years without being able to write a word, because all we could do was try to absorb all of this. The surprising thing, after a while was that we would go to places where there were lots of resources, and pretty good — not great, but pretty good — education and good market locations next to railroads or highways or something, and there'd be 75% unemployment. Then we'd go to places where there weren't a lot of natural resources and they started from nothing, and yet the place was starting to boom economically and socially as well. The place was coming together, really, as a community.

And the thing that struck us was it was really clear the tribes who had their governmental acts together were the ones that were taking off. That lesson is a lesson for economists. We kind of know it. Economists have Nobel Prizes about it — that there has to be an institutional base. Otherwise you waste your resources, otherwise you can't get access to capital, otherwise you can't hang on to a good teacher if everything's chaotic.

The Harvard Project, while always having that economic development component, really started to have this governance component — the key, if you think about it, is true in nations around the world, right? Nations around the world can have lots of resources and they can fall flat on their faces unless they can govern well. And we often say, “From Poland to Potawatomi, it’s the same story.” That was really the kind of “aha!” moment for us: wow, this really is about sovereignty and self-government, and the economic development then becomes really a consequence, not a cause, of the rebuilding of tribal nations.

Randy, as a Native Hawaiian economist, how did you first encounter the Harvard Project's work, and how has your background shaped your vision for leading it?

RANDY AKEE: I was a master's student at Yale, doing research on economic development in Indigenous and Native communities, and their work came up. I went back to Hawaii and worked in the state Office of Hawaiian Affairs Economic Development Division. My interest was, how can these things be applied, and how can I get people to listen to me? And the answer was, nobody was listening to me. I did not have the authority to make change, and that's when I really realized I needed to get a PhD. That's when the Harvard Project and the Kennedy School all seemed like the right place to come together.

The work that was being done already was completely in the field of view of what I thought needed to be done in Hawaii, but also elsewhere. And that just wasn't replicated anywhere else. It's not sort of mainstream, but it should be, as Joe has been saying. There are lessons learned, there are successes, there's innovation that occurs that are not just applicable to Native nations. They're lessons that could be applied broadly.

I started taking classes in economics in high school because I always wondered how and why, in our case, land ... why much of it had been lost. And why so many in my family were poorer than the average resident of the state of Hawaii. Those kinds of experiences started the questions. Joe, myself and all of our other colleagues that work in this area, we're trying to reduce those obstacles to entry and encourage more students, faculty, government officials who are interested to come on over. We're happy to share what knowledge we've got, because putting this out there only benefits the rest of us.

Over the years, what's the most important finding from the Harvard Project's work?

KALT: Let me say a word about both the substantive finding and the process finding. Economists all knew that institutions mattered. But for a long time we treated those institutions as given. But without the governance to set down the rules of the game and a rule of law, and increasingly we say a rule, in our context, of Indigenous law — a rule of law in which just because someone's your cousin, or just because you're married to somebody doesn't get you anything special. When you're productive in our community and you're a good member of our community, then you'll succeed.

A bunch of tribes asked us to facilitate their conversations about constitutional reform in the first half of the 2000s. One of the leaders from the Grand Traverse Band in Michigan says we had a rule of law in the old days — everybody knew their role. The elders knew their role, the young people knew their role. Well, it was that preeminence of the role of the rules of the game and stabilizing them in a way that isn't just favoritism to one group or one party or one faction or one's family. That was the number one insight.

The process piece we learned came early on in our work. I had Chairman Richard Real Bird from the Crow Tribe, who was one of my mentors, come speak at Harvard. I had a bunch of Native graduate students there, mostly law students. And one of them pipes up: “You damn professors. You come out here, and you do your research, you publish in your obscure journals, and we, the communities, never get anything out of it.”

We made a commitment. We're going to do our research. We're going to do the best possible research we can. But every single piece of research we produce, we're going to try to turn it into something useful that decision makers and the tribes can use. So the governance focus, the importance of sovereignty — you can't have real governance without sovereignty. And if you don't back up your sovereignty with good governance, you're going to fall apart.

What do policymakers still miss about Indian Country and tribal economies?

KALT: Within the tribal governments, there's such a long history of what I think of as intentional institutional dependence created by the federal government that implicitly defines that new council member's job as, "I got to get more out of the federal government." The breakout tribes break through that. They say, my job is to govern my community, and the federal government is just another government I have to deal with. So within the tribes, there's still that. It takes a while to figure out your job is not to just run and get the next grant. Your job is to govern, make the laws of your nation.

On the non-tribal government side, the number one problem is the lack of knowledge. The typical US congressperson, the typical mayor of the immediate off-reservation town, the typical state governor and his or her staff — they just don't understand tribal sovereignty and what it means. We give little lectures. We call them Tribal Sovereignty 101. So that lack of knowledge of Indian Country on the outside, and then the mindset of "we are truly governments" — getting that mindset really embedded. Those are the big challenges I see.

AKEE: The biggest component is taking tribal governments as governments, and not clubs. The federal agencies in recent decades have really taken more seriously their responsibility to not just have tribal consultations with tribal nations, but also to elicit input into processes and decision-making. That's a new day.

And then secondly, understanding that there's emerging research from which advocacy is occurring and that people can access that data. Increasingly, it is more available. And so there are ways to make more informed policies, programs and budgets that can be traced back to actual data and evidence. That's a big improvement.

The Harvard Project and Honoring Nations really champion success stories in Indian Country.

AKEE: That's the point. It's not all doom and gloom. Things aren't perfect, but there are actual successes. And if we don't account for them, if we don't showcase them, the prevailing wisdom is that it's all doom and gloom and nothing works. But there are other places where they're leading the charge. And that needs to be celebrated and championed for the fact that, hey, what aspect of this is replicable? What can we do where we live to replicate that amazing policy that revitalizes the local economy or leads to better conservation efforts in our watershed?

That was really exciting for me, because there's a long history of that here already. It's the foundation of the Harvard Project. The resiliency — that's what it comes down to. There's resiliency in these tribal nations, and people know this. And here are some actual case examples of that.

Joe, what makes Randy the right leader for the Harvard Project at this point in time?

KALT: Within academia, Randy is clearly — and he knows this, this won't even embarrass him — the leading scholar doing work on not only economic conditions, but social conditions, education, health and governance in Indigenous communities. There's just simply no question about that.

What I remember about Randy as a graduate student was that it was risky — oh, you're working on tribal economies. They're too small, they're idiosyncratic. The rest of us fancy economists don't have anything to learn from Indian Country. It was risky for Randy to do that. So when I say committed, I mean he saw it. He said, screw it. I'm going to go for it and do the best research I can do, but have it matter to these communities.

Randy's also the founder of AERIP. He’s a leader within the profession in a way that continues this process of making it easier for young scholars to come along and make careers here and not be confined to never getting tenure or being ignored. Randy is a leader in that and also in mainstreaming the ideas.

Indian Country's got this valuable ability to teach the rest of the world, because while people think, oh, the communities are relatively small, that smallness gives us, as a researcher, a chance to get our hands around what's going on. Everything they're doing is a microcosm. Their housing program is a microcosm. Their law enforcement is a microcosm. And it gives a researcher an opportunity to really learn and draw out the lessons that France can learn from, that the broader world, the United States, the countries in Africa, can learn from. That ability to mainstream the research is clearly an objective behind Randy's appointment as the first holder of this new endowed professorship, the Julie Johnson Kidd Chair in Indigenous Governance and Development.

Randy, what part of Joe's legacy do you want to make sure carries forward?

AKEE: One of the things that just always carried through — when you talk to his students, when you talk to tribal leaders who've worked with him — is that he's very engaged, and he's there working on behalf of and for the benefit of the tribes themselves and the students here at the Kennedy School.

I just take that as a service delivery. And that component I find very refreshing, because the model of academics is there's no service. The service is in the pursuit of your own research, and that's about it. So I think that aspect is something I try to emulate and replicate. What Joe, Steve and Manley working in this area have shown is that it also garners better research, because you're made part of the community in that work process, in that sharing of information, of stories, of anecdotes. And so when you're working with, as opposed to looking at or peering in, it all comes out better.

Where do you see Native governance and development heading over the next 25 years?

KALT: What I've been able to watch through my career is this amazing rise in the capacities and the sophistication of tribal governance — not just the formal tribal government, but the governance of businesses, the community activists, people engaged in trying to move the community forward. Just a tremendous increase in the capacity and the sophistication, coupled with doing it from their own base, meaning their own base of values and culture. You don't have to just adopt what the state of New Mexico does. So it's this culturally grounded capacity and capability.

We're in a whole generational shift right now in tribal leadership. In the early days, the tribal leaders who'd gotten involved with AIM … they were from that generation who were manning the barricades. And the barricades that have to be manned now are different. You play the game differently. You have to be very sophisticated. And we see the success that breeds.

On the challenges side, we have a problem that's not getting better —the haves and have-nots among the tribes. The tribes who have lots of financial resources now, they've built those institutional departments, and they've got an army of lawyers, often from their own tribe now. But that challenge of the haves and have-nots is a big one. It affects the way Indian Country presents itself to DC policymakers. We know it creates some tension across tribes. So I think that's the challenge — tremendous progress, but these are growing pains.

AKEE: I think an emerging area we'll see is really in climate change and environmental concerns, natural resources. Tribal nations are engaging with climate change and scarcity of natural resources — water is going to be big. These climate change mitigation efforts and tribal nations start from (a) perspective of Indigenous knowledge. There are thousands of years of evidence and expertise. But then the ability that has emerged with the lawyers to be able to negotiate cross-state, cross-governmental agency, cross-stakeholder groups — I think those models are going to be some of the leading lessons that will come out and possibly be models for other places. The same issue is going to happen in Southeast Asia, the Amazon, parts of Europe. And I'm increasingly encouraged by the ways in which this type of innovation emerges.

If tribal leaders are early in their governance or economic development learning, what's your advice?

KALT: You can talk the talk about sovereignty, but you gotta walk the walk. What I mean by that is, we're a tribal nation. Live up to the word nation. What that means is building the capacity to actually run yourself, run your own community. One of the lessons we learned early on, we'd walk into an office at a tribe that was taking off. You could feel it. Everybody's job was to take over more — to 638 their cops, or whatever the challenge might be — to take back more and more. That's our job, to do it. We gotta do it well.

That means building the capacity to make your own decisions, from your constitution to the language taught in your schools and the lunch served at the school. Those are your decisions. That's what sovereignty is. The lawyers can fill rooms with books and articles on what tribal sovereignty is. Sovereignty's simple. It's you make your own decisions. You run your own community, from the lunch program to your constitution.

AKEE: You don't always have to recreate the wheel. And that's where listening comes in, and that's where seeking out wisdom comes in. You can get a lot of help, you can get a lot of assistance. Ultimately, you got to implement it yourselves, and you've got to do it. But there are models, there are examples, and there's accumulated knowledge on how things could be done, should be done, have been done. Seek those out.

That's why coming to the Harvard Project is great, because there are lots of these really great examples. And I think that's part of the job, is making sure that these examples and this information is out there for others to use going forward so that they don't have to start from scratch. And this is one of the things Joe, Steve, Manley and (Harvard Professor) Miriam Jorgensen and others have been really adamant about — yes, academic papers and academic research is a core, but it should be accessible and it should be available. If you don't understand it, come and talk to one of us, and we'll break it down.