- Details

- By Elyse Wild

- Economic Development

A new analysis from Native Americans in Philanthropy provides additional context around Indigenous representation within the industry’s professional ranks.

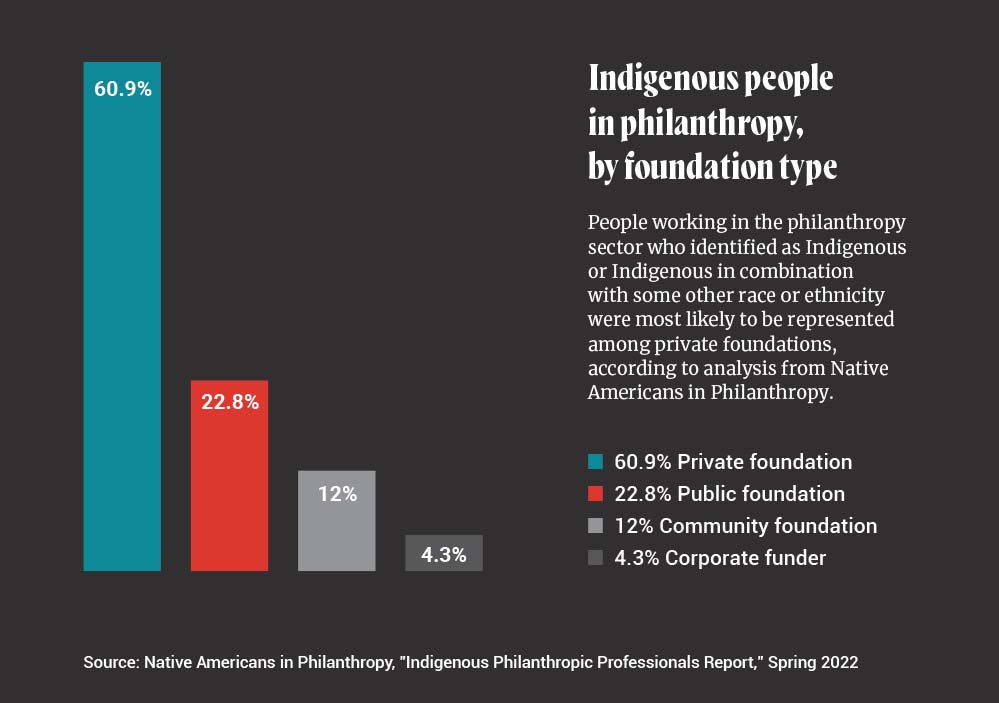

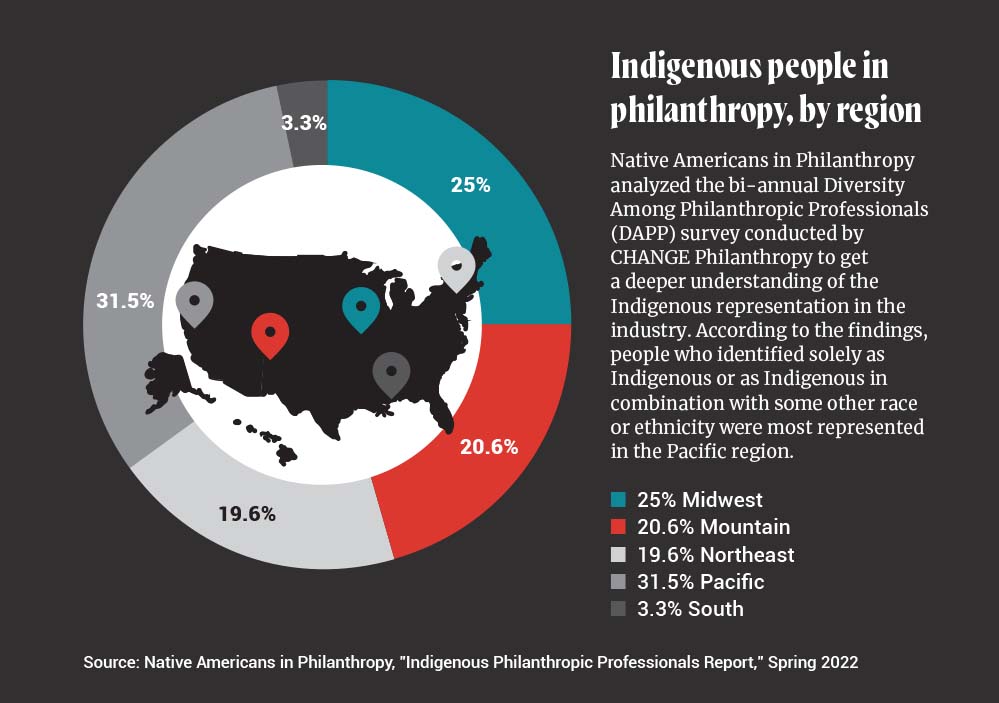

Using data from the bi-annual Diversity Among Philanthropic Professionals (DAPP) survey conducted by CHANGE Philanthropy, Native Americans in Philanthropy determined that people who identify as Indigenous most likely work with private foundations (61 percent) and identify as female (62 percent). Additionally, 75 percent of Indigenous philanthropic professionals are in their 40s or younger.

Indigenous professionals also tended to be most represented in the Pacific region of the Western U.S., according to the Indigenous Philanthropic Professionals Report issued in March.

Native Americans in Philanthropy used the release of the report to call for additional “evaluative and intentional” research that will spur the philanthropic community to “to strengthen representation of Indigenous communities and professionals” and “serve as a mechanism for change.”

Vicky Stott, program officer of racial equity and community engagement at the Battle Creek, Mich.-based W.K. Kellogg Foundation, said Native Americans often fit well within the industry because of shared value system.

“When we think about the heart of what philanthropy is and what it is intended to do is really connected to those Native values of seven generations,” Stott (Ho-Chunk) told Tribal Business News.

According to the Indigenous Philanthropic Professional Report, Stott is part of the 3.8 percent of philanthropic professionals who identify as Indigenous.

While the number of Native Americans working in philanthropy has grown 50 percent since 2018, the industry falls short in funding Native communities. According to NAP, less than 0.4 percent of the financing by large foundations goes to Native communities.

“The thing is that number has been there for quite a while,” said Brittany Schulman (Waccamaw Siouan), the vice president of Indigenous leadership and education programs at NAP, who authored the recent Indigenous Philanthropic Professionals Report.

“That is unfortunate given the huge deficit of need in our community and the great work that is happening. Part of the issue, of course, is philanthropy itself and the inability to understand Native Americans and how these are not one-and-done issues,” she said.

According to a 2021 report by the Center for Effective Philanthropy, Native American nonprofit leaders report having less positive relationships with their foundation funders than other nonprofit leaders, primarily because of the lack of understanding on the foundation’s part. Positive relationships were credited to foundations investing time and energy in learning about the nonprofits and approaching funding as a collaboration.

“We have been pushing philanthropy for quite a while to fund general operations and not make it tied to a specific program,” Schulman said. “Multi-year grants can be a game-changer for nonprofits and tribes in Indian Country. Philanthropy has a long way to go to understand some of the contexts so they can do their job better in funding our people.”

The W.K. Kellogg Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Bush Foundation consistently rank among the top four large foundations directing funds to Indian Country, giving a total of $1.2 billion since 2006.

When the COVID19 pandemic began to spread in the United States in March 2020, it was almost immediately apparent that tribal nations were disproportionately affected, with Indigenous communities experiencing the highest mortality rate among racial groups. Even so, 67 percent of Native American nonprofit leaders who responded to the Center for Effective Philanthropy reported that no foundations provided new funding in 2020.

While it is clear that Native representation in philanthropy is critical to bridging gaps in understanding that lead to lack of funding, data on how Native American professionals enter philanthropy remain scarce. Schulman notes the absence of any clear career pipeline.

“You stumble into philanthropy,” Schulman said. “You are working in a field, and then a position becomes available to you through a relationship. You join a foundation, and then you are marginalized and tokenized. … There is a lot of burnout.”

Native Americans in Philanthropy CEO Erik Stegman (Carry the Kettle First Nation Nakoda) agrees.

“Right now, the pathway to philanthropy for Natives is so disconnected,” Stegman said. “There is a lot of potential impact being lost because there isn’t a clear connection.”

Native Americans in Philanthropy was founded in 1989 to promote equitable and effective philanthropy in Native communities. Stegman joined the organization in 2020 after serving as executive director of the Center for Native Youth at the Aspen Institute.

“There is a lot of work to be done to build bridges between this very bizarre philanthropic world that very few people understand and to educate them about who we are,” Stegman said. “We have been invisible for far too long in the sector, and we are really trying to be a hub as we build as much power in the sector as possible.”

Native Americans in Philanthropy’s various initiatives work to create a Native presence at different levels of philanthropy while facilitating collaboration between Indigenous communities and funders. Its Native Youth Grant Makers program is a yearlong course aimed at introducing Native youth to philanthropy, while the Native Voices Rising initiative supports organizing, advocacy and civic engagement in Indigenous communities. The Tribal Natives Initiative brings tribal nations and the philanthropy sector together to identify priorities and build partnerships.

“Tribes themselves have been completely invisible in philanthropy,” Stegman said. “For too long, tribal communities have been in a deficit framework. … There is so much money in philanthropy that we should be demanding to invest in the big vision we have. The more we bring stakeholders — federal partners, tribal partners, philanthropists — together through coordinated partnerships, the more potential we have.”

Stott offers that when she stepped into her role at the Kellogg Foundation in 2016, she knew it was vital for her to be visible to advance awareness for Native issues in the industry.

“There are just not enough of us Native people working in philanthropy, and I knew it was really important that people in philanthropy see people like me working in this space,” she said. “When there isn’t enough of us at the table, it creates an absence of our voices. … Like so many communities, we want to be able to make decisions for ourselves and affirm who we are.”