- Details

- By Caryn Mohr, Center for Indian Country Development

- Economic Development

Researchers Matthew Gregg and Robert Maxim reflect on how the pandemic has entrenched labor market inequalities.

[This story was originally published by the Federal Reserve's Center for Indian Country Development and is used with permission.]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, articles on remote work have been anything but remote. Considerable attention has gone to the potential benefits and costs of remote work for employers and employees. But when researchers Matthew Gregg and Robert Maxim dug into new data from the Current Population Survey, they hit on an aspect of the remote work economy that’s received less attention: the involvement of Native American workers in the remote work revolution. In a report for the Brookings Institution, the researchers detailed how more than any other group, American Indian and Alaska Native workers are less likely to work remotely.

Center for Indian Country Development (CICD) writer and analyst Caryn Mohr sat down with the researchers to discuss what they found, why their findings matter, and what we can do to address the gap. With Caryn and Matt at their office in Minnesota and Rob joining from a family home in Massachusetts, the interview was conducted—you guessed it—remotely.

The views cited in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System.

We’ve all seen articles about the potential benefits and costs of remote work, but information on disparities in access to remote work seems less prevalent. What prompted you to dig into the data?

Matt: For me, the motivation was to shed light on the labor market activity of Native Americans by using some new questions in a relatively up-to-date dataset. Early in the pandemic, COVID-19-related questions were added to the Current Population Survey, and that opened new possibilities for analysis. One of those questions pertained to teleworking, asking if workers had worked for pay from home in the last four weeks due to the pandemic.

Rob: I think another motivation was that Native Americans tend to be overlooked when it comes to economic data that breaks out groups by race. We get lumped into the “other” category or just don’t exist in the data at all. Matt and I saw this Current Population Survey data as a good opportunity to get a sense of how Native people were faring in the labor market during COVID. I think there had been very little discussion of that prior to this piece coming out.

For those of us who don’t work with employment data every day, can you explain in plain language what data you looked at?

Matt: The Current Population Survey, or CPS, is a survey sponsored by the U.S. Census Bureau and Bureau of Labor Statistics. It gets published every month, provides information on labor markets, and, fortunately for us, contains enough American Indians and Alaska Natives in the sample to tell a story. When we refer to “Native American workers” in the context of this analysis, we’re talking specifically about those who identified as either American Indian or Alaska Native alone or in combination with other races, regardless of ethnicity, on the survey.

Rob: The CPS essentially serves as the primary source of labor statistics for the U.S. In May 2020 the survey started asking questions to understand how workers were being affected by a variety of COVID-19-related indicators—things like workers’ inability to work due to COVID and their ability to access paid leave during COVID. One of the questions added was the remote work question.

What did you find?

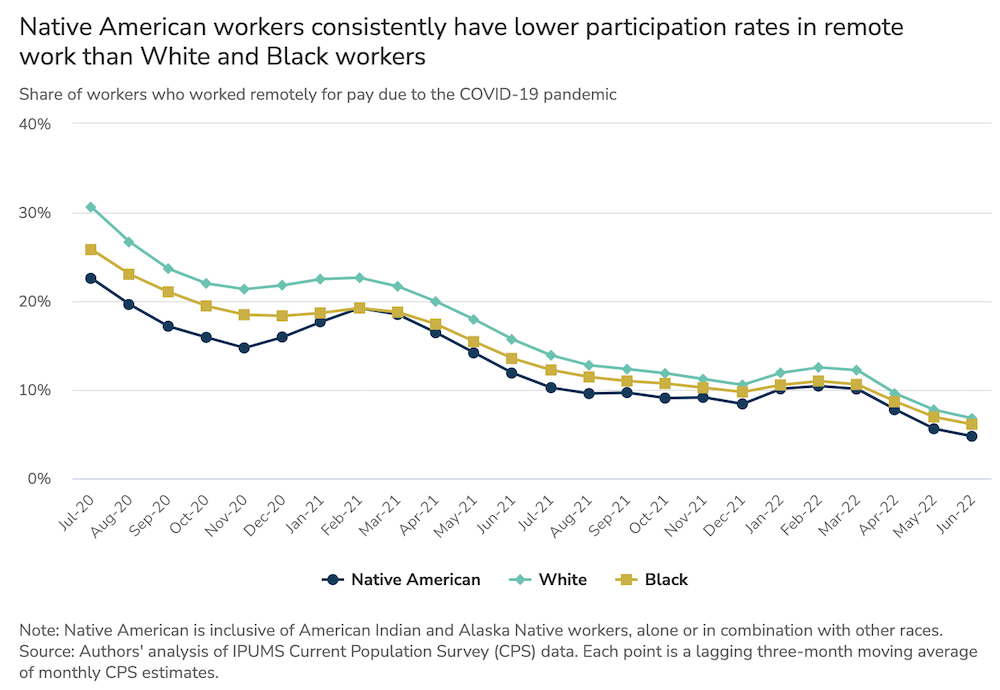

Matt: At every stage of the pandemic we looked at—from May 2020 to June 2022—Whites were more likely, on average, to work from home than Native American workers. Of all the groups we studied, Native workers were the least likely to work from home.

One logical explanation for the gap could be differences in the occupations held by each group. For example, Native Americans are more likely to be frontline workers in jobs that often cannot be done remotely. But what we found is that while occupational differences accounted for almost all of the racial disparities in remote work during the first year, they explained much less of the gap as the pandemic progressed. That is, in the second year we looked at, from May 2021 to April 2022, about a quarter of the gap between Native American and White workers could not be explained by occupational differences.

In other words, occupational differences were of critical importance when the pandemic started and then became less important—still important, but less so—over time. That finding begged the question, If employment differences aren’t driving the telework racial disparities that we’re seeing, what is?

Was there anything that surprised you?

Rob: It was really interesting in the second year of the pandemic that even as the remote work gap got smaller as workers returned to the office, the share of that gap that was not explained by differences in jobs actually grew. (See Figure 2 in the original Brookings report.) I think I anticipated that occupational differences would be the largest factor, but I don’t think I realized that in the first year of the pandemic they would explain nearly all of the difference. And then watching other factors, whatever they might be, grow in importance in the second year of the pandemic was really interesting to see.

I think the top-line number that we found was also a bit surprising. At the peak of the pandemic remote work surge, from May to July 2020, White workers were working remotely due to COVID at a rate 8 percentage points higher than Native American workers. During this time, 23 percent of Native American workers worked remotely due to COVID. That number was 31 percent for White workers at the same time. I don’t think I anticipated the magnitude of the difference there.

How do these findings connect to other research you or others have conducted?

Matt: I’ve done some work measuring the tribal digital divide. Roughly speaking, access to fast, affordable Internet is scarce not only in Indian Country but even when compared to Internet access just outside Indian Country. The size of the tribal digital divide is pretty substantial, so it’s not hard to imagine how that could contribute to a remote work gap.

Rob: I’ve looked at Native workers’ access to the labor market in general, and one point I’d add is that, in my view, the lack of access to remote work is really a symptom of a much broader problem of underinvestment by the federal government into tribal economies and Native workers. To step outside the econ space for a moment, I think when you look at the geography of where Native people live it’s not a coincidence that many tribes and reservations are either at the periphery of metro areas or in nonmetro rural areas with less access to resources—digital infrastructure, employment opportunities, or otherwise. There’s this really difficult history around the federal government terminating tribes’ reservations, disenrolling tribal citizens, and forcing Native people to move to urban areas with minimal skills training and few employment opportunities. A lot of that was happening even into the 20th century—into the mid-20th century.

My view, and what I’ve talked about in a lot of the work I’ve done, is that we’re still seeing the consequences of those policies when we look at how Native people interact with the labor market. Even today when there are tribes being forced to put a disproportionate amount of resources into maintaining their land and sovereignty in the face of efforts to take it away, it leaves fewer resources to focus on economic and community development. Discussions around things like Native American access to remote work, and how Native Americans engage in the labor market in general, can’t be decoupled from these broader questions around tribal sovereignty and self-determination.

Thank you for bringing that crucial context into the story. To bring the story close to home, how might a Native American worker and their family experience this gap?

Rob: There was a really good article by Zoe Han at MarketWatch that looked at some of this. She told the story of a Shoshone-Bannock family and their attempts to manage both remote work and remote schooling for their kids without proper broadband access. They ended up basically relying on two mobile phones to provide all of their data because they couldn’t get broadband service like you or I would take for granted. I grew up on what would be considered my tribe’s homelands, but it’s a pretty densely populated area in eastern Massachusetts. My parents have broadband and I’m doing this call right now from my childhood living room, but you see the type of challenges that were laid out in that article across much of Indian Country.

And it’s not just broadband. Native workers face a variety of challenges to working remotely that are exacerbated compared to other workers. We talk about some of these challenges in our Brookings piece. They live in overcrowded housing at higher rates than other workers. The federal government’s own studies have shown that a significant share of housing in Indian Country is substandard. Native Americans are also more likely to live in multigenerational housing. All of that means that some Native workers are going to have a harder time setting up a home office, doing video calls, or having their kids dial into class in a way that a lot of other Americans just took for granted during the pandemic.

Matt: Rob makes an important point that there were preexisting gaps when the pandemic started. What we’re seeing in a lot of research is that the pandemic has really exacerbated preexisting disparities.

We’ve especially seen disparities exacerbated when it comes to health disparities. As we’ve learned, the pandemic has been devastating from a health standpoint for Native Americans. At the start of the pandemic, Native Americans’ life expectancy was already below other groups’, and it’s dropped more than any other population. From 2019 to 2021, the life expectancy of American Indians and Alaska Natives dropped by almost seven years. When you consider our main finding, I think it’s a sign that a lot of folks were put in a risky predicament because of their occupation.

It's sobering to consider how the pandemic has widened gaps, and how different gaps can exacerbate each other. What do you think could be some of the long-term implications of the remote work gap?

Matt: One thing Rob brought up over conversations is that remote work is an avenue for retention of tribal members in their homelands. If you live in the middle of South Dakota but have the ability to work remotely for a job in Chicago, that might allow you to stay in your tribal community. In that way, currently poor Internet access—based on the historic underfunding of broadband deployment in tribal communities—could have consequences far beyond employment opportunities, which are of course important on their own.

Rob: I think there’s an important question around how much of a missed opportunity this is. My personal view is that technologies like remote work provide an opportunity to connect Native workers to jobs that aren’t local as well as to connect tribal and Native-run businesses to talent elsewhere. Folks in Indian Country often weigh the balance between tradition and modernity. For me, this is a clear-cut example of where modernity serves as an opportunity to advance Native economies. When Native workers and Native nations are grappling with underinvestment in areas like broadband or housing or other barriers to remote work that they’ve been dealing with for years or decades or more, I think the remote work gap just perpetuates existing inequalities.

My world view is that it not only hurts Native workers and hurts Native nations, but it also hurts non-Native people as well. Healthy tribal economies support Native people, but they also provide opportunities for employment, business opportunities, trade, and supply-chain connections for non-Native workers and firms. There are fewer of those opportunities for Native people and for non-Native people when Native nations are still contending with this underinvestment that they’ve been dealing with for centuries.

That’s a great point to bring in—that equal access is in everyone’s best interest.

Matt: There’s been research estimating pretty sizable spillover effects of tribal economic activity into nontribal areas. In a lot of rural areas, a county’s employment is driven by the local tribe. The tribe is the major employer.

Rob: Tribes as anchor institutions.

Matt: Right, exactly.

Part of CICD’s mission is to provide actionable data and research. What actions could be taken to support equal access to remote work?

Matt: At a minimum, we need information on Native American labor market activity so we can even have that conversation. The Bureau of Labor Statistics could report on the racial disparities to make the data more accessible to the public. These statistics, presently, aren’t on their website. Rob and I were able to do this analysis because we’re trained in working with microdata. Publicly accessible data could go a long way toward rekindling some of the conversations about not just racial disparities but Native American-White disparities in particular.

Rob: I really view the question of remote work as a symptom of a set of much broader issues around investment in Native workers and the economies of Native nations. Matt and I took that view in our Brookings piece and proposed a variety of investments to that effect. A significant action we recommend is that federal policymakers establish what we call a “Native Homeland Economic Development Grant.” We envision a significant competitive grant program that would encourage diversity in Native nations’ economic activities. It could be modeled after things like the U.S. Economic Development Administration’s Build Back Better Regional Challenge program and the Indigenous Communities program that it created using American Rescue Plan funding. The goal would be to diversify tribal economies and create more opportunities for employment and business creation, which has really positive spillover effects for the potential of remote work. That idea is not new. Randall Akee, a scholar at the University of California, Los Angeles (and recent CICD research fellow), proposed a similar idea in a piece for the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

I think education also plays an important role. Workers with a college degree tend to have greater access to remote work, but Native education programs have historically been underfunded at basically every level. We need to provide more funding for pre-K-12 education in Indian Country as well as for tribal colleges and universities and Native American-serving nontribal institutions. I think the elementary, secondary, and higher education discussion has to be part of this.

And then, as Matt has discussed, I think infrastructure investment needs to be at the center of any of this. Even though the federal government has made these historic investments into things like tribal housing and broadband over the past few years as part of its pandemic response, those investments cover just a fraction of total needs in those areas. We did some of the math in a footnote of the Brookings piece, and there were substantial gaps that remained even if we took pretty conservative estimates of the needs of Indian Country.

Matt: As we discussed, the remote work disparity is driven in part by employment differences, and those employment differences are driven by educational attainment and other factors. Education is a treaty right. Those treaties are historic, but they often have language that in exchange for land, tribal members should have affordable and available access to education. In 2023, what should that look like? One action area could be respecting and revisiting treaty rights that will speak to issues like education availability, infrastructure quality, and health care quality. That would be a great actionable policy solution: Honor treaty rights.

The data have clearly revealed an important—and complex—story. If you had to share it in 30 seconds to catch attention in today’s sound-bite world, how would you tell the story? And what do you hope happens in the next chapter?

Rob: To me, the story is that Native American workers have the lowest access to remote work, as well as lower levels of employment and higher levels of unemployment in general, and that’s a function of decades and centuries of bad government policy. I hope the federal government can move to a position of truly investing in tribal economies, which would give Native nations the resources they need to develop their own economies and provide new opportunities for their citizens.

Matt: I would go with Rob’s great answer. There’s more work to be done here.

Matthew Gregg works as a senior economist in Community Development and Engagement at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Matt has conducted research on a wide range of topics related to tribal economic development and is a member of the Association for Economic Research of Indigenous Peoples.

Robert Maxim works as a senior research associate for Brookings Metro, where he conducts research and designs policy proposals for Brookings Metro’s managing disruption portfolio, exploring how economic trends such as technological change and globalization affect people and places. Rob is a citizen of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe.

For additional details on Matt and Rob’s analysis, see their original report for the Brookings Institution.

Caryn Mohr is a writer/analyst for the Federal Reserve’s Center for Indian Country Development, where she contributes to the team’s research, policy, and engagement work and creates content and communications that support economic development in Native communities.