As an enrolled member of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe in Montana, I know what poverty looks like because I grew up with it.

My early years were marred by poverty and a troubled childhood. I proudly served our country in the U.S. Air Force in the Korean War and, in 1964, had the honor of representing the U.S. in the Tokyo Olympic Games.

In many ways, serving in the military and athletics paved the way for me to not only survive, but to thrive. A successful marriage and raising a family came later and led me to run for public office. After two terms in the Colorado Legislature, I served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1987 to 1993 and in the U.S. Senate from 1993 until my retirement in 2005.

In 1997, I became the first American Indian to chair the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, the committee with the bulk of legislative authority over tribal matters. Regardless of the party controlling the Senate, the committee has always operated on a nonpartisan basis with an eye toward resolving the challenges tribal communities face.

The Context of 1997

When I took the committee gavel, Indian Country was still registering on the lowest rungs on all social and economic indicators: unemployment, poor health, substandard housing and all of the related social pathologies.

Indian gaming was still in its infancy, and there was much litigation in federal courts with states and tribes often at loggerheads. The year before, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision in Seminole Tribe v. Florida, holding that tribes could not sue states for failing to negotiate — or negotiating in bad faith — to secure a tribal-state gaming compact. Afterwards, Congress was inundated with legislation to address the Seminole decision, and Indian country — often led by the National Indian Gaming Association and the National Congress of American Indians — was clamoring for the ever-elusive “Seminole fix” to authorize tribes to have a remedy with recalcitrant states.

Key Pillars of the Philosophy

Having lived on the Southern Ute Indian Tribe’s reservation for many years, I witnessed tribal leadership at its best. The tribe began a decades-long effort to separate its business operations from its governance and became the premier natural gas-producing tribe in the country. The tribe’s model was one that influenced me greatly, both as a senator and as chairman of the committee.

My guiding principles included a strong preference for local (tribal) decision-making, bringing discipline and accountability to federal agencies and programs, helping tribes create the kind of business and investment-friendly environments where commercial activity could flourish, and striving to help tribes generate jobs and household incomes for their members.

Legislation and Tribe-Specific Bills

Early on, the committee focused on reforming existing programs like the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act (NAHASDA) at the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Native American Programs Act in the Administration for Native Americans. Every year, NAHASDA pours more than half a billion dollars into housing and community development and, likewise, the ANA makes economic development grants to tribes. They are among the most successful programs available to tribes.

To cultivate non-gaming options for tribes, I put forth the Native American Business Development, Trade Promotion, and Tourism Act, to be operated in the Department of Commerce. Since then, many tribes have ventured into these lucrative industries and have become regional and national leaders.

I also knew that whatever reforms the committee might be able to tackle, such as much-needed changes to Section 81 of the federal code dealing with contracts with tribes, there were dozens, if not hundreds, of other reforms in Title 25 that were — and I believe still are — needed. I proposed, and the president signed, the Indian Tribal Regulatory Reform and Business Development Act on Indian Lands Authority to do just that.

Probably the most effective way to reform federal agencies and improve services to Indian people is to “tribalize” the programs through the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act and the Tribal Self-Governance Act. In 2000, my bill to make self-governance permanent in the Indian Health Service became law. The law also launched demonstration projects in self-governance in other offices and programs of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Realizing that many tribes possess enormous energy resources and reserves, for years, the committee worked on ways to streamline the federal permitting processes to provide tribes more authority and latitude over their own lands and resources. Though I retired in January 2005, these efforts paid off later that year when Congress passed the Indian Tribal Energy Development and Self-Determination Act as part of the Energy Policy Act of 2005.

The committee also heard from Indian Country on the need for additional civil and commercial legal assistance. Working with the Legal Services Corporation, I introduced what became the Indian Tribal Justice Technical and Legal Assistance Act, to provide legal assistance providers more resources to benefit businesses on Indian lands.

Indian Country has long had problems attracting capital to their communities. In 1998, I made a proposal to establish the Native American Financial Services Organization to make capital and financing more readily available for housing, community and commercial development in tribal communities. Unfortunately, it never became law, but soon afterward, tribal leaders created the Native American Bank to perform many of the same functions.

We were successful in reforming and expanding the scope of the Indian Financing Act of 1974, with key reforms and amendments made in 2002.

As an artist and jeweler, I am especially proud of the enactment of the Indian Arts and Crafts Enforcement Act of 2000, which reforms the federal legal protections against counterfeit Indian arts and crafts by expanding the category of entities as to who may file suit under the Act, as well as increase penalties and attorneys’ fees for those legal actions.

It was also apparent that legislation affecting a single tribe could be life-altering for that tribe’s members. Examples that became law during my tenure include Indian land and water settlements and land transfers and exchanges. Many times, these bills bring funding, land and water and, ultimately, jobs and development to the affected tribes.

In the course of my chairmanship, members of the committee from across the country put forth these types of bills, dozens of which became law.

All in all, I am proud of my service in the House and Senate and as a tribal member, and I’m especially pleased with the actions of the committee under my leadership and that of my friends and colleagues from both parties who served with me.

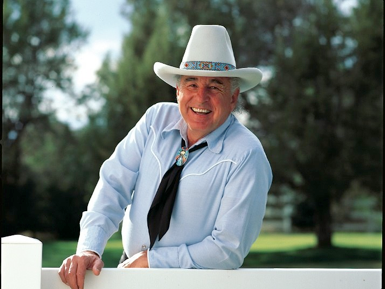

Ben Nighthorse Campbell is a member of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe. Campbell is a Korean War veteran and captain of the 1964 Olympic Judo Team. He served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1987-93, and in the United States Senate from 1993-2005. He is the only American Indian to Chair the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs (SCIA). Senator Campbell would like to thank his former SCIA Staff Director, Paul Moorehead, for his assistance preparing this column.