- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

- Economic Development

Despite disproportionately adverse effects that COVID-19 has brought on Indigenous economies, tribal governments have responded to the pandemic with innovation and resilience.

That was the overarching theme from tribal leaders, economists and professors who spoke Wednesday during a web series hosted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis’ Center for Indian Country Development (CICD), a research institute that aims to increase economic opportunities in Indian Country.

The 90-minute session included panelists Shelley Buck, Tribal Council President for Prairie Island Indian Community in Minnesota; Matt Gregg, a senior economist for the Center for Indian Country Development; Randall Akee (Native Hawaiian), an associate professor at the UCLA Department of Public Policy and Public Administration and in the American Indian Studies Program at UCLA; and Chairman Leonard Forsman of the Suquamish Tribe in Washington.

The event was moderated by Miriam Jorgensen, research director for both the Native Nations Institute at the University of Arizona and its sister program, the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development. CICD Executive Director Casey Lozar (Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes) introduced the webinar series as the first of four programs slated throughout 2021.

Lozar told Tribal Business News that the first web series was an exploration into lessons learned from the pandemic thus far. Research over the last 12 months, in part conducted by the center itself, shows Native Americans have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19 when compared to other groups.

“What are some of the barriers that have been exposed?” Lozar said to preface the web series. “What are some of the policies that tribal leaders, as well as policymakers, need to be thinking about, and really then becoming educated about to really support long-term growth in Indian Country?”

Here’s a look at several themes to emerge from the presentations.

REVENUE LOSS

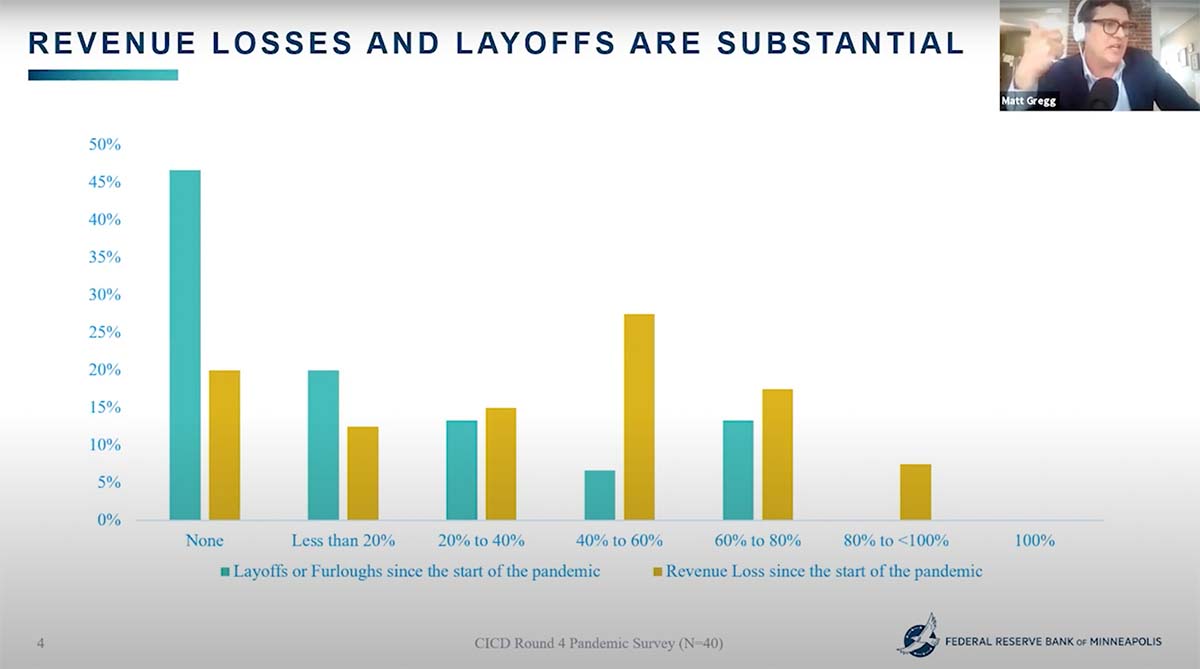

The CIDC conducted five surveys throughout Indian Country since the start of the pandemic. The latest — distributed to 40 tribal enterprises, governments and organizations throughout the country earlier this month — looked at revenue loss.

According to CICD economist Gregg, new data show that state and local government revenue loss from 2020 are only between 2 percent and 5 percent, although survey results “tell a very different story from Indian Country.”

The survey sample showed the majority of respondents experienced a revenue loss between 40 to 80 percent since the start of the pandemic. While nearly half of respondents said they resorted to some furloughs and layoffs, 65 percent of respondents said they either didn’t have to furlough any employees, or furloughed less than 20 percent of their workforce. Anecdotally, Gregg said that’s because many tribes have kept staff on payroll despite business shutdowns.

Sixty percent of the tribal government respondents have had to cut government services in some form, and roughly half of the tribal government respondents said that they’re behind on debt payments.

“And so to put this all together, the survey results show that the impact of the pandemic on Indian Country and tribal governments in particular is in stark contrast to the impact of the pandemic on local and state governments,” Gregg said.

TIME TO DIVERSIFY

Tribal Council President Buck of the Prairie Island Indian Community said that the pandemic that temporarily closed the tribe’s resort and casino and forced the furlough of 90 percent of its employees brought many of the tribe’s greatest fears to light.

Because of Prairie Island’s close proximity to a nuclear waste storage site and nuclear power plant, the prospect of a forced shutdown of tribal businesses is something the tribe has lived with daily, even before this pandemic, Buck said.

“We made the decision to continue providing benefits for furloughed employees, and it was the right thing to do for our people,” Buck said. “But it was also a very expensive decision. The pandemic reinforces the need to focus on a safer future for our tribe.”

As well, Chairman Forsman said the Suquamish Tribe’s casino and tourism business has only reopened at 60-percent capacity, and consequently is bringing in around 60 percent of its former income. Additionally, the tribe’s seafood business that ships clams to China was among the first industries to take a hit in the pandemic.

In response to a loss of profit, Forsman is considering ways to diversify the tribe’s revenue streams.

“We really are looking at taxation here as an opportunity … to be able to tax on-reservation businesses that are owned by non-Indians,” he said.

In 2015, Forsman said the tribe found success by opening a cannabis store on the reservation that has provided additional tax dollars directly into tribal coffers. The tribe has used some of the funds to buy back land taken by the federal government in the early 1900s.

STRUCTURAL BARRIERS

In his presentation, researcher Akee discussed his study of the relationships between COVID-19 case rates and tribal infrastructure.

“What we did find was that there was a positive correlation between the percent of homes lacking complete pumping facilities and COVID-19 cases on reservation,” Akee said.

Additionally, he said case rates were lower among households on a reservation that spoke English.

“The takeaway from this is that there are underlying obstacles and structures, one being infrastructure,” he said. “Just in basic facilities and access to things like water, but then secondarily public messaging on important aspects of … how you prevent the spread of COVID-19. It needs to be facilitated and accessed in multiple languages.”

Additionally, Akee looked at behavioral changes of reservation residents in the pandemic by using cell phone tracking data.

By looking at the cell phone data of people who lived on a reservation during government or tribal induced shutdowns, Akee found that the distance people traveled to grocery stores was reduced by about half a mile over time, as compared to individuals living off the reservation (likely non non-Natives).

“So what it means is that people were … keeping it close,” Akee said. “They were shopping at less further afield retail operations.”

Further analysis showed that the kind of stores that reservation residents shopped at shifted from grocery stores to convenience stores.

“This is … an indication of the lack of resources and or facilities for reservation communities,” Akee said. “In the future, we might consider that … being able to shop relatively close to home and not have to go further afield is one of the things that we didn’t realize was happening in a time of pandemic.”

As well, a study conducted during the 2007 recession in conjunction with CDCI showed that businesses located on reservations were more likely to be resilient to economic downturn than their off-reservation counterparts.

“Over time, actually, on-reservation enterprises in the nation as a whole actually had higher survival rates in industries such as lodging and food, arts and entertainment, education, health care, public administration, and wholesale retail, than their counterparts located right off the reservation,” Akee said.

While it’s too soon to make the same prediction for the current period, Akee said that evidence might still hold true.

TRIBAL LIMITATIONS

Limitations that weaken tribal governments’ ability to respond to the pandemic included the initial difficulty in securing loans, the calculation the government used to allocate CARES Act funding, and a lack of tribal consultation and lack of understanding on the part of the federal government.

To prepare for the unknown, Forsman said the Suquamish Tribe has borrowed more than it anticipated needing as a step to prepare for another potential shutdown, and shifted to approving quarterly budgets, as opposed to an annual one.

Buck said the Trump administration’s regulations on how emergency funds could be spent forced the Prairie Island Indian Community to divert scarce resources to fight the pandemic.

“We really felt like we had one arm tied behind our back when it came to that,” she said. “A lot of that boils down to the lack of consultation. The federal government just forced this formula down our throats without really thinking through what it meant for individual tribes.”

A LESSON IN RESILIENCE

CICD’s Lozar said the largest takeaway from the webinar was the idea of tribal resiliency, the importance of diversification and putting community members first.

“I think there’s going to be a lot more that we can … learn from the pandemic that will inform policy conversations down the road that will have lasting impact on our tribes,” Lozar said. “Thinking … seven generations from now, what are those policies we need to have to really ensure that we can put forward all the strategies and the priorities for long-term economic stability in Indian Country?”

CICD will host three additional webinars on tribal enterprise diversification and tribal taxation in Indian Country in spring, summer and fall, Lozar said.