GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. — The Grand River Bands of Ottawa Indians will have to wait at least another four months before the tribe hears from the U.S. Department of the Interior about its petition for federal acknowledgement.

The Interior Department’s Office of Federal Acknowledgment (OFA) notified tribal officials on Oct. 4 that it was instituting a 120-day extension to its previous deadline of Oct. 12 to issue what’s known as a proposed finding on the tribe’s petition.

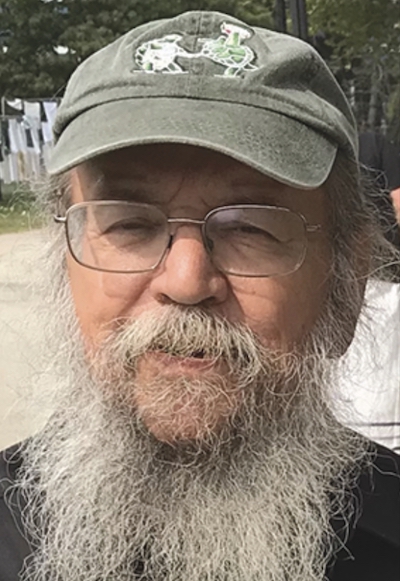

Ron Yob, chairman of the Grand River Bands of Ottawa Indians, added the letter to a stack of nearly two dozen such extensions that he’s received since the tribe began this process 28 years ago this month.

“I would have been more shocked to see it not get extended, really,” Yob said. “It’s sad to say, but you almost expect it.”

In what’s become a seemingly endless cycle of delays since the tribe first indicated that it planned to seek federal recognition in October 1994, the OFA now has until Feb. 9, 2023 to rule on whether the Grand River Bands of Ottawa and its approximately 500 members should receive the benefits of sovereignty that comes from formal federal recognition.

Previously, the OFA has issued a string of extensions to the process, in addition to a two-year, pandemic-related suspension from April 2020 to April 2022.

“This letter is to advise you that the Department of the Interior (Department) needs additional time to issue the proposed finding,” R. Lee Fleming, director of the Office of Federal Acknowledgement, wrote in a letter to the tribe. “This 120-day extension will allow the Department time to complete its review of the petition and issue a PF under the applicable regulations.”

Yob said he’s heard no other formal communication from the OFA about the process.

“You just have to let it play out,” he said.

While the state of Michigan recognizes the Grand River Bands of Ottawa Indians, that status comes with few benefits. A favorable ruling by the OFA would pave the way for the tribe to maintain government-to-government relationships with the federal government, access federal programs and resources such as the Indian Health Service, and exercise its sovereign treaty rights for activities such as fishing.

Historically, the Grand River Bands of Ottawa Indians included 19 bands of Ottawa people who lived along the Grand River and other waterways in present-day Southwest Michigan, spanning the cities of Grand Rapids and Muskegon. Ancestors of the current members were signatories of numerous agreements with the federal government, starting in 1795 with the Treaty of Greenville.

The majority of its current enrolled members live in and around Kent, Muskegon and Oceana counties.

In the OFA’s bureaucratic process, the agency must weigh the tribe’s petition against seven mandatory criteria. To qualify for federal recognition, a tribe must:

- be identified as an American Indian entity by reliable external sources on a substantially continuous basis since 1900;

- comprise a distinct, continuous community and demonstrates that it existed as a community from 1900 until the present;

- maintain political influence or authority over its members as an autonomous entity from 1900 until the present;

- provide a copy of the entity’s governing document, including its membership criteria;

- consist of individuals who descend from a historical Indian tribe or from historical Indian tribes that combined and functioned as a single autonomous political entity;

- be composed principally of persons who are not members of any federally recognized Indian tribe; and

- never have been the subject of congressional legislation that has expressly terminated or forbidden the federal relationship.

Beyond the bureaucratic process through the BIA, the Grand River Bands also previously sought a legislative path to federal recognition. In 2005 and again 2007, the tribe worked with the late Sen. Carl Levin and current Sen. Debbie Stabenow, both Democrats, to sponsor federal legislation that would have given the tribe an “expedited review” of its petition and granted it federally recognized status if the BIA failed to act within a given timeframe.

Levin’s 2007 bill made it as far as a hearing before the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs before it died.

Yob said a similar legislative push “is always a possibility,” but acknowledged that the upcoming midterm elections would likely delay any such efforts.

Earlier this year, Grand River Bands’ ongoing petition process also played into Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s decision that ultimately nixed the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians’ proposal for a $180 million off-reservation casino in Fruitport Township.

Whitmer said she had been placed in an “impossible position” by the Department of the Interior, which was forcing her to issue an opinion on Little River’s casino proposal before the OFA’s original Oct. 12 deadline for Grand River Bands’ federal recognition.

While Interior had agreed to take the former Great Lakes Downs property into trust for the Little River Band, the tribe’s plans needed the governor’s approval as part of a “two-part concurrence” process because the site was located outside of its traditional territory in Manistee and Mason counties.

“My concurrence with the Little River Band’s two-part determination could frustrate the Grand River Bands, which may wish to open their own gaming facility on tribal lands not far from Fruitport Township,” Whitmer wrote in an April 15 letter to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland.

The Grand River Bands only issued a formal stance opposed to Little River’s plans in May of this year. Yob also has repeatedly said the tribe has no position on whether it would ever seek gaming given that its sole focus currently must be on the federal recognition process.

With the tribe’s petition process closing in on a 28-year milestone this month, Yob said he’s buoyed by the recent outpouring of support from the community, including bipartisan members of Michigan’s state Legislature and federal delegation, various community organizations, business groups and residents.

“I have to keep fighting. If I were to stop, the next generation would probably have to start from ground zero,” Yob said.

While he noted that while he’s not heard anything affirmative from the OFA about the process, “I’ve also never been told no, either,” Yob said. “I’d have to think that if a ‘no’ was on the board, we’d have heard that by now.”

--

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story originally appeared in regional business publication MiBiz and is republished with permission.