- Details

- By Rob Capriccioso

- Arts and Culture

When N. Scott Momaday, Louise Erdrich and Sherman Alexie burst onto the literary scene in their respective eras, they were widely celebrated for their unique gifts of prose. The authors made money via their passions, tasted fame and became symbols of Indian success in mainstream America.

They also were supposed to usher in a tide of Indigenous authors whose successes could be built upon to develop a pipeline for increasingly more Native storytelling to be consumed by mainstream readers and Indian Country alike. Their work was even labeled in academia as part of a “Native American Renaissance” — a controversial term to some since American Indians have long been storytellers before any Eurocentric or Western book world existed to decide what should or should not be considered worthwhile.

Still, they and a handful of their peers were celebrated with great hope. Yet with each major Indian triumph in the world of publishing, a dearth often followed. Industry insiders contend it was as if publishers of each of these giants of Indian literature had fulfilled their quotas and then quickly moved on, searching for the next shiny object that would appeal to the masses. The publishers, no doubt, kept returning to their proven winners — hence the numerous respected works of established American Indian authors — but taking risks on newbie Natives seemed less of a goal.

[RELATED: ‘Firekeeper’s Daughter’ author Angeline Boulley takes the book world by storm]

With the current success of author Angeline Boulley, a citizen of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians whose debut novel, “Firekeeper’s Daughter,” hit number one on The New York Times young adult charts this spring, people in the publishing industry, academia, and in Indian Country are all wondering if a new wave is here. They also question if this new wave will become more lasting and widespread than those of the past, rather than crest and ebb away.

Debbie Reese, a former teacher and professor of American Indian studies, is closely monitoring the current situation. Her popular blog, “American Indians in Children’s Literature,” has long highlighted challenges Native writers face, as well as the problems of Indian representation present in literally volumes of books.

“This is very different from what we have seen in the past,” said Reese, a Nambé Pueblo citizen. “This is a big wave — we are seeing so many milestones for Indigenous writers who have been traditionally shut out of the major publishing houses. There’s a lot of stuff going on behind this big wave.”

Courtesy photo.

Courtesy photo.

Foremost, society seems to be more open to learning about Indigenous stories, culture, advocacy and history. We Need Diverse Books, a Bethesda, Md.-based nonprofit organization that grew from the social media hashtag #weneeddiversebooks, is responsible for a large chunk of the current spotlight, but its advocacy didn’t happen in a vacuum. Scholars in this field say the broader Black, Indigeous and People of Color (BIPOC) movement and positive Indigenous developments that have come along with it — like the name change of the Washington, D.C. football team — are part of the greater shifts at hand.

Reese celebrates Boulley’s star turn as the latest in a series of recent mainstream successes of Indians in literature. She points to Joy Harjo, a Muscogee citizen, being named as U.S. Poet Laureate in 2019 and continuing in that position for three nominations to date, as well as the American Library Association finally beginning to feature the American Indian Library Association’s awards announcements at its annual gala as especially meaningful.

Individual Indian book achievements also loom large. In 2020, “Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story” by Kevin Noble Maillard, a Seminole Nation citizen, won the Sibert Informational Book Medal. In January, Tlingit and Haida illustrator Michaela Goade won the Caldecott Medal for “We Are Water Protectors,” becoming the first non-White winner ever of the prestigious award. Eric Gansworth, an Onondaga Nation citizen, also took home the Printz Honor Medal this year for his “Apple: Skin to the Core,” and he was named to the longlist for the National Book Award.

‘VICIOUS CYCLE’

Corporate publishing houses are certainly involved in the ongoing shift. For instance, a dozen major publishers and imprints participated in a bidding war for Boulley’s novel; she ended up with a reported seven-figure advance from New York City-based Henry Holt and Co.

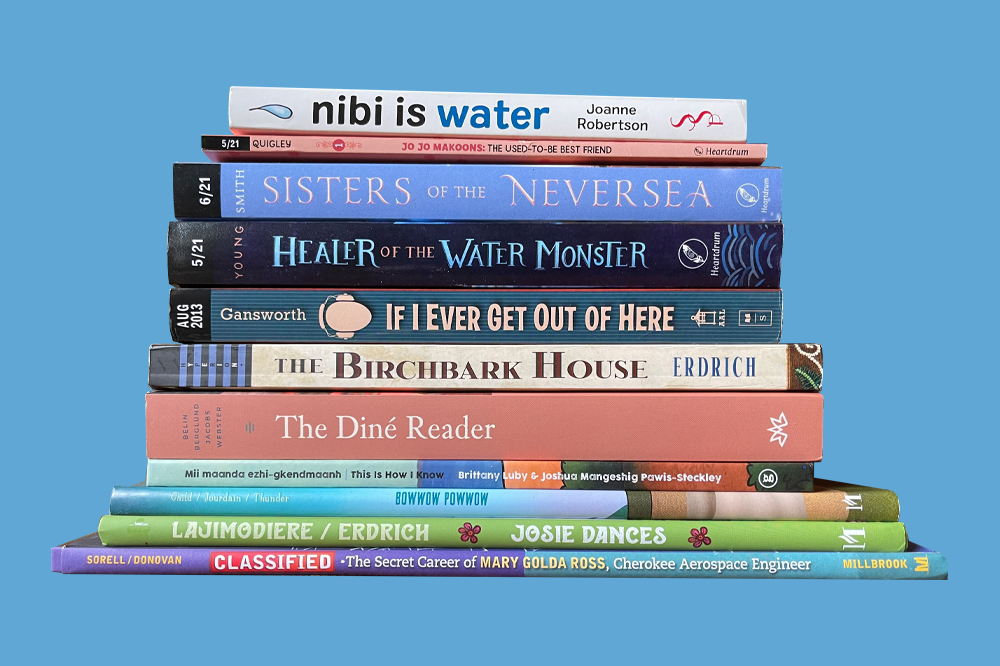

Meanwhile, HarperCollins Publishers LLC, also based in New York, has recently established Heartdrum, an imprint solely dedicated to fostering Native talent. Cynthia Leitich Smith, a Muscogee Nation member who leads the imprint, also helps organize an annual long-weekend LoonSong retreat that occasionally invites Native writers to Minnesota for kinship and networking. Heartdrum is also funding a new virtual “We Need Diverse Books Native Writing Intensive” workshop to take place each year, starting this August.

Leitich Smith, who mainly focuses on the child and young adult markets, says she’s witnessing more openness to Native voices from the major literary trade houses.

“Heartdrum is part of that, but so are presses like Levine Querido, Charlesbridge, Lee & Low, Reycraft, and the Kokila imprint at Penguin,” Leitich Smith said. “My feeling is that we’ve reached a sort of critical mass, and we’re a tight-knit and supportive creative community — constantly in touch and also actively mentoring beginners.

“Supporting small, Native-owned university and tribal presses remains important to all of us.”

Indeed, Indigenous presses have been a crucial part of nourishing Native writers all along, but visibility and making enough money to keep operating have been perennial issues.

Want more tribal business news? Get our free newsletter today.

Arthur Levine, founder of the independent and Indigenous-friendly Levine Querido LLC in New Jersey, where Gansworth, Anton Treuer, and Darcie Little Badger have lately been published, knows quite a bit about the world of corporate publishing, and the negative experiences American Indian writers have often faced within it.

“It’s been a vicious cycle of mainstream publishers not valuing Native talent, and therefore Native talent being discouraged from approaching mainstream publishers,” Levine said. “I think it is partly a matter of publishers just needing to try a little harder. There is no paucity in Native American communities of both art and text.”

Levine, who published and edited J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series while at Scholastic, has attended the LoonSong retreat, and said he’s made many great connections there, including meeting Boulley.

Having been in the industry since 1984, Levine said that corporate publishers are too focused on imitation, and when a societal trend appears to subside, publishers simply move on to find the next one. (Levine says he “misses nothing about being part of that system.”)

When this way of business is applied to genres like the fantastical wizards of Harry Potter, it is a different story than when it is applied to people and cultures.

“It’s a problem,” he said. “I think that’s why there’s been a kind of lurching forward and then losing steam (for Indigenous writers). It’s been a story of inequitable inclusion.”

“Publishers do all kinds of jacked up things to Native writers,” adds Reese, who, for her work on the American Indians in Children’s Literature blog, was asked by the American Library Association to deliver its 2019 Arbuthnot Honor Lecture. “They want guts, they want ceremony, they want dance, and a lot of Native writers are, like, ‘I don’t know about that, I don’t want to do that.’ So a lot of nice books don’t get published.”

CREATING A PIPELINE

Another question that looms over the industry hinges on whether the big league players are simply catering to another popular trend for Indian-themed work right now to chase financial success. Many observers wonder whether the publishers will move on from the trend as easily as they did from the multiculturalism movement of the 1980s and ’90s.

“The longer the door is left open and the more successes are made out of Indigenous books — the more they are highly lauded, and the more they sell — the authors of those books will have an identity and an audience that is there,” Levine said. “I wouldn’t say permanently because nothing is permanent.

“A hugely important factor is the effect these books … have on young Native writers and artists,” he adds. “If you grow up thinking, ‘Wow, I could be Angeline Boulley, I could be Michaela Goade,’ then more people who are talented have the belief that they should go for it.”

Along with the bidding war, a Netflix deal from the Obamas’ Higher Ground production company and the substantial advance for “Firekeeper’s Daughter,” Boulley is turning out to be a litmus test for where an entire industry is headed in Indigenous literature.

“I hate to put a lot of pressure on Angeline’s book, but there is a lot of weight on that book because it is doing so well,” Reese said. “It has the potential to really shape how people think about our writers and the books that they write and what they give us in those books.”

Boulley is well aware of these major concerns, and she has worked hard to prioritize strong business judgment and the importance of mentorship, while continuing to tell unique, complex Indian stories. She also acknowledges that a little bit of luck got her to this “golden ticket” moment in time.

As she works on her second novel, Boulley doesn’t want her example to “become another situation where all the attention goes to one, and yet there are so many other great stories and great voices out there.”

“We always fear Native authors being seen as a trend instead of a course correction,” Boulley said. “The hope is that publishers will recognize that there is lasting commercial and literary value to Native stories and stories by Native authors. That’s what we all hope.”

--

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story has been updated to note that Levine Querido LLC has published Anton Treuer, not David Treuer. Also Morgan Rath, a publicist with Macmillan Children’s Publishing Group (Macmillan oversees Henry Holt and Co.), clarified that Boulley received a seven-figure, two-book deal.