- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

- Sovereignty

AUGUSTA, Maine — After the Maine Legislature denied the 81-member Kineo Tribe of Malecite Indians’ bid for state recognition, the tribe now says that it will pursue federally recognized status instead.

On Feb. 25, the Maine Legislature shot down a bill for state recognition of the Kineo Tribe, a Native American group with historical documents tying them to the region since the 1800s. All five federally recognized tribes in Maine opposed the bill, which proponents say swayed the 11 to 1 legislative vote.

David Slagger, former Malecite Tribal Representative to the Maine Legislature who has been pushing for recognition since 2012 when an identical bill was stymied, said state recognition would be helpful in seeking grant funding for cultural preservation and language revitalization, specifically by building a cultural resource center, a welcome center and a museum. Slagger is a member of the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians, and said he is also a descendant of the Kineo Malecites.

Language in the failed bill deems that recognition “may not be construed to create, extend or form the basis of any right or claim to land or real estate in the state or any right to conduct gambling activities prohibited by law.”

“We weren’t asking for gaming, we weren’t asking for land,” Slagger told Tribal Business News. “We were simply asking for recognition. They’re not pretendians, or trying to be something they’re not.”

State Rep. Jennifer Poirier, the only legislature to vote in favor of the state recognition because there was “no doubt” in the historical data, said there were no objections that the Kineo Tribe is indeed Malecite.

“The objections were that there was no clear commission or advisory board in place,” she said. “My concern with that objection was that the Kineo have been the only tribe to seek recognition at the state level in Maine that anyone is aware of.”

Slagger said the tribe has now set its sights on federal recognition, citing the timing of the “very Indian friendly” Biden administration.

All five tribal chiefs of the Passamaquoddy Tribe at Pleasant Point, Passamaquoddy Tribe at Indian Township, Penobscot Nation, Aroostook Band of Micmacs, and Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians lobbied the Maine Legislature to oppose the vote on the basis that it did not follow process.

“Being a tribal nation is sacred, and verification of such claims are necessary to protect the identity of our people, our ancestors, and ancestral territories,” the tribal chiefs wrote in a letter submitted to the state Legislature. “We fear that state recognition of a tribe through a bill that does not require a process could set a harmful precedent.”

While there is no official state criteria in Maine for tribal recognition, Slagger said the Kineo Tribe of Malecites has met the federal criteria for tribal recognition, including proving 121 years of establishment, a distinct community that has existed in the area since historical times, a continuous form of government, and a lack of termination from Congress.

The Kineo Tribe of Malecites used to gather at Kineo mountain, along with other Native American tribes in the area, to collect flint from the mountain to create arrowheads, according to Slagger.

“It’s no question,” Slagger said. “We’re using the same process that my tribe did in 1973, which is to introduce a bill to say, ‘We want recognition.’ To say that there’s no process, well of course there’s a process, because they themselves used the process.”

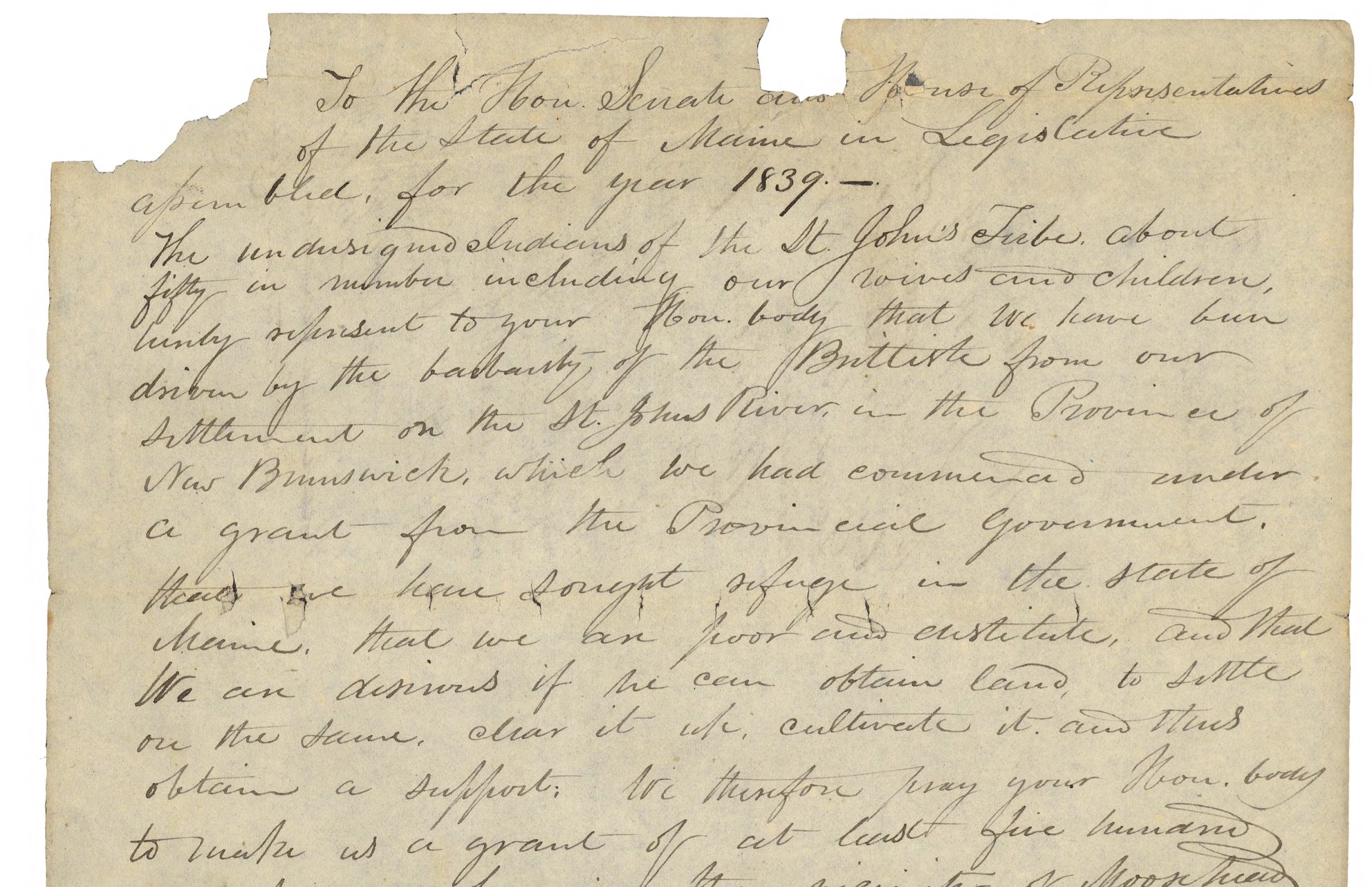

The Malecite, once called the St. John Tribe, have a 1839 petition asking for 500 acres of land after they had “been driven by the barbarity of the British from our settlement on the St. John River.” The Maine Legislature denied the request, but the document proves the Malecites’ existence in the area at least 182 years ago, with the names of 50 people whose lineage can be traced to the present day.

The Malecite, once called the St. John Tribe, have a 1839 petition asking for 500 acres of land after they had “been driven by the barbarity of the British from our settlement on the St. John River.” The Maine Legislature denied the request, but the document proves the Malecites’ existence in the area at least 182 years ago, with the names of 50 people whose lineage can be traced to the present day.

One descendant, Richard Dyer, a former chief of the Aroostook Band of Micmacs Tribe, told Tribal Business News that tribal leaders previously opposed the Kineo Tribe’s state recognition out of fear it would take federal dollars out of their coffers.

“I couldn’t quite make the connection, because they’re apples and oranges,” he said. “The tribes are sort of ignorant by saying that, because it doesn’t matter what the other tribes received from the federal government, they’ll still continue to receive the same amount, because tribal dollars (are) based on headcount, it’s based on your per capita need. So the more tribal citizens you have, the more dollars you receive from the federal government.”

“I can’t for the life of me understand why my own people would be against my own people,” Dryer added. “I just can’t fathom it.”

While tribal leaders did not respond to requests for comment for this report, Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission Managing Director Paul Thibeault, who submitted testimony backing the tribes, said the biggest reason the tribes and Commission would not support state recognition hinged on the terseness of the bill.

“This is a one-line bill that would just create an undefined status of state recognition,” Thibeault said. “I think that was the basic problem.”

He added that while he can’t speak for the tribes, he could understand that they might be wary of a state-recognized tribe that would potentially have access to some federal programs with a broader definition of tribe beyond federal recognition.

“I would think there was some concern that now it could be diluting a limited part of funding in some programs,” he said.

For the tribes, that concern likely won’t be dismissed with the failed bill.

Slagger said the Kineo Tribe will seek federal recognition through a partnership with an undisclosed firm in Washington, D.C. Federal recognition requires a tribe to meet stringent criteria, and takes longer than state recognition, which is why Slagger said the tribe first pursued the latter.

The state of Maine does not currently recognize any tribes that aren’t recognized by the federal government.

“With the Biden and Harris administration, and a Native head of the Department of the Interior, we feel that this is a perfect time for a tribe like us to seek federal recognition, because we believe that the Biden-Harris administration is very Indian friendly,” Slagger said. “It’s going to be interesting to see if the other tribes are going to oppose our federal recognition and claim no process, because that’s what they claimed in the state bill.”